Most of us are probably familiar with one or more high-profile agoraphobes, such as writer Shirley Jackson, Beach Boy Brian Wilson, and perhaps most notably, the reclusive billionaire, Howard Hughes. Then there’s arguably the most famous fictional agoraphobe of all time, if that’s even a correct diagnosis.

I’m talking about Nero Wolfe, the larger-than-life gourmand, orchid grower, and private detective, who is loathe to move his robust seventh-of-a-ton from his famed brownstone in the interests of plying his trade. Oh, and he’s not all that inclined to leave the house for any other reason, now that you mention it.

Except when he does. And that’s where it gets interesting. Because, like so many of Wolfe’s peccadilloes, there’s some wiggle room built in. Yes, he spends two two-hour sessions a day communing with his 10,000 orchids – except on the very rare occasions when he doesn’t. No, he doesn’t shake hands – except when it suits his needs and perhaps will help give him a psychological edge over someone. And yes, his pronounced distaste for members of the opposite sex is a matter of record, but there are those rare women—Archie Goodwin’s Lily Rowan among them—who receive his grudging seal of approval.

So is Nero Wolfe an agoraphobe? I’m not qualified to make that diagnosis, but let’s consider Merriam-Webster’s definition of the condition, “abnormal fear of being helpless in an embarrassing or unescapable situation that is characterized especially by the avoidance of open or public places.”

Given that definition, I’d venture to say that Nero Wolfe is not an agoraphobe. I

It’s not clear exactly what’s behind Wolfe’s reluctance to leave the brownstone. Perhaps it has something to do with his need to be in control of a situation, to make his criminal opponents and others come to him and thus keep them off balance. Perhaps, it’s as simple as Archie has suggested on numerous occasions, he’s just plain lazy. In any event, it certainly can’t hurt that he has a highly capable right-hand man, who can do all of the legwork and report lengthy interactions without missing a detail.

Of course, Wolfe does leave the house in a number of the novels and stories, not just for personal reasons but also to do what he claims to never do – to conduct business. It’s a plot device that Wolfe creator Rex Stout employed to great effect. Since readers are conditioned to believe that Wolfe won’t leave the house, when he does it’s an event of some monument, along the lines of Moses descending from Sinai with a pair of stone tablets in tow.

This is not the place for an exhaustive listing of these forays, but there are a few

In some cases, Wolfe must leave home because the authorities demand it. In The Silent Speaker (1946), Wolfe and Archie are called to police headquarters, where things get heated and Wolfe actually strikes the inspector who is filling in for his old friend and nemesis Cramer, who has been relieved of duty. In Too Many Detectives (1956), one of the Wolfe novellas, detective and sidekick are summoned to Albany for questioning by the office of New York’s secretary of state, which licenses private investigators. In The Next Witness (1955), another novella, the pair are subpoenaed to testify in a murder trial.

But there are three books in particular in which Wolfe’s adventures beyond the brownstone are decidedly unusual. In Some Buried Caesar (1939), Wolfe’s fears about unreliable mechanical contrivances like automobiles are confirmed. On their way to an orchid show, with Archie at the wheel, the car blows a tire and plows into a tree. The duo must hoof it out of there and end up being chased by a bull. Archie makes it to safety while Wolfe is stranded on a rock in the middle of the pasture.

In the Best Families (1950) finds Wolfe tangling, as he did twice before, with mobster Arnold Zeck and this time around things get serious. The two lock horns and a suspicious package delivered to the house turns out to only contain a canister of tear gas. Wolfe disappears without warning, for what turns out to be an extended period of time, operations at the house are shut down and the orchids are moved to another location.

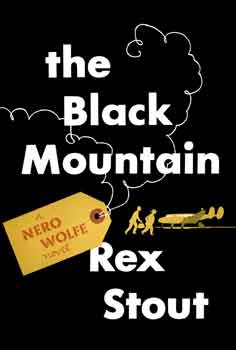

But it’s The Black Mountain (1954) that’s perhaps the biggest departure for Wolfe, both in the figurative and literal sense of the word. The title refers to the English translation of the name of Wolfe’s native land—Montenegro—and it’s there that he and Archie wind up as the events of the book unfold.

If you’ve read enough Wolfe, you could safely assume that there are few people near and dear to the big man’s heart. His grudging admiration for Archie shows through on rare occasions and one suspects that he respects Inspector Cramer and perhaps even enjoys the frequent sessions in which they peck at and goad each other.

But it’s restaurateur and fellow Montenegrin, Marko Vukcic, that Wolfe makes no bones about referring to as a friend and an occasional jaunt to Vukcic’s eatery is also on the list of his rare forays out of the house. So when Vukcic is murdered Wolfe goes to great lengths—travelling all the way to Montenegro—to make sure that justice is served. Once he and Archie arrive they must make their way around in various types of conveyance. There are also a number of lengthy journeys on foot, no small feat for a corpulent fellow whose idea of exercise is turning his head to look at the clock on the wall.

So given all of this it’s probably not entirely accurate to refer to Nero Wolfe as an agoraphobe. Perhaps it’s just that, to use his own words again, “It is always wiser, where there is a choice, to trust to inertia. It is the greatest force in the world.”

William I. Lengeman III is a freelance journalist with a fondness for gourmet tea and traditional mysteries. He writes about the former at Tea Guy Speaks and the latter at Traditional Mysteries.