The opening credits begin with shots of sunny beaches scored with some generic Hawaiian music, but then the credits end and the sunlit scenes dissolve into the same beaches at night. That’s when the noir starts kicking in. At a nightclub in Honolulu, a pretty girl and a man with a scar on his face sit down to listen to a song. There is eye contact between the man and some creep at another table. The pretty girl intercepts a note meant for her companion, and she gets up and meets the creep in an office in the back of the nightclub. He tells her he intends to shake down the man with the scar over a long ago bank robbery. Bad idea. She shoots him in the forehead.

What is the relationship between these people? We don’t quite know yet. The girl goes to retrieve the man with the scar and tell him what has happened. His name is Chet Chester (Wendell Corey), and we infer that he’s something of a underworld power broker in Honolulu now. He’s not a totally bad guy, though, and he declines to let the girl, Sally (Nancy Gates) take the fall for the murder. He turns himself over the cops.

Then the plot cuts to California where we find a young war widow named Donna Williams (Evelyn Keyes). She’s engaged to be married, but when she gets word of the shooting down in Hawaii she becomes convinced that Chet Chester is actually her dead husband, Randy Williams. Donna flies down to Honolulu against the wishes of her fiancé, but before she can come face to face with Chester a couple of things happen: first, Sally is murdered by an associate of Chester’s named Roger Kong who is looking for Chester’s missing fortune. Then Chester escapes police custody to track down the killer. Now Donna has to make her way through the seedy underbelly of Hell’s Half Acre, Honolulu’s most squalid district, searching for Chester as he searches for Sally’s murderer.

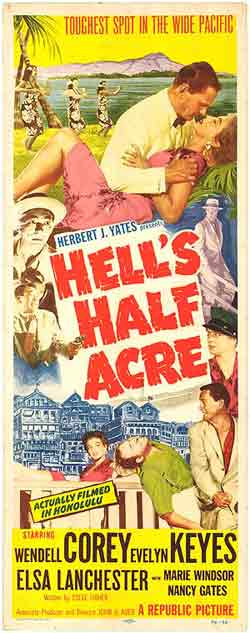

Hell’s Half Acre (1954) was written by Steve Fisher, a pivotal figure in the development of film noir. Fisher wrote the novel I Wake Up Screaming which, in 1941,was made into one of the first noirs (though it was marred in the process of adaption), and he later co-wrote the brilliant, and woefully underrated, Roadblock starring Charles McGraw and Joan Dixon. His work on Hell’s Half Acre is a fine example of noir plotting, plunging us into a story with several different stories running beneath the surface of the action. The relationship between Corey and Keyes, for example, has unexpected maturity and pathos. Fisher also fills out the edges of the script with a lot of interesting character parts. He’s not always so deft at tying up logical inconsistencies (the exact working out of the plot is a little garbled in the final scenes), but there’s every chance that by the end you won’t much care about the resolution of the plot. I mean that in a good way.

The film was directed with great style by John Auer (City That Never Sleeps) who was working once again with Republic Pictures’ resident master of photography, John Russell. This is a gorgeous film to look at, with the sandy beaches of Honolulu giving way to pure noir visuals. Hell’s Half Acre itself is a shadowy no-man’s-land of slanted angles and damp streets (in the way it juxtaposes a supposed daytime paradise with its seedy dark side, the look of the film may remi nd some hardcore noir fans of the Jamaican vacation hell described in Goodis’s The Wounded and The Slain). The Republic crew also included veteran composer R. Dale Butts who does an amazing job here of finding the musical equivalent of the cinematography. The film begins with standard aloha fare, but by the end Butts has slowed the music down and made it ominous. If “ominous Hawaiian music” sounds oxymoronic, then see the film to judge for yourself. Butts’s music is absolutely effective.

nd some hardcore noir fans of the Jamaican vacation hell described in Goodis’s The Wounded and The Slain). The Republic crew also included veteran composer R. Dale Butts who does an amazing job here of finding the musical equivalent of the cinematography. The film begins with standard aloha fare, but by the end Butts has slowed the music down and made it ominous. If “ominous Hawaiian music” sounds oxymoronic, then see the film to judge for yourself. Butts’s music is absolutely effective.

You could really say the same thing about most of the movie. It’s anchored by good performances by two of noir’s best actors. Wendell Corey is a perfect fit for Chester because his face is naturally weighed down with the knowledge of terrible deeds. Those sad eyes of his have seen things Corey would rather forget, and this role uses his bottomless world-weariness to great effect. Likewise, Evelyn Keyes is an inspired choice to play Donna. Keyes had enough pluck for three actresses, and she makes a sexy, fun tour guide through the twists and turns of this plot. There’s something else about her, though. Keyes has a restless mind. When she and Corey finally meet, it’s interesting just to watch her watch him and piece together what has happened to him since the war.

Corey and Keyes are surrounded by a plethora of good actors filling out the margins of Fisher’s cast of characters. Philip Ahn tears up the screen as Roger Kong, the murderer everyone is after. He’s a nasty piece of business, and he’s joined by a weak-willed henchman named Tubby Otis (played with sleazy relish by Jesse White). And Otis has a horrible, double-crossing wife played, of course, by the Black Widow herself, Marie Windsor. Her part, sadly, is all too brief, but Windsor plays the living hell out of the role. She’s sexy, nasty, and hilarious—all in a role that lasts about fifteen minutes. Watching both Windsor and Keyes, you have to wonder how Hollywood managed to miss their power. These were great movie stars.

Hell’s Half Acre isn’t perfect (there are some goofy coincidences here and there, and the precise layout of Hell’s Half Acre itself is a little confusing), but this is a long lost gem of B-movie greatness. Track it down.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of Hell on Church Street.

Read all posts by Jake Hinkson for Criminal Element.

PS. Tracking it down, as it turns out, should be easy to do. The film is available for Instant Watch on Netflix.

Was the ending as dark as I thought it was? You don’t often have good-guy police pulling that kind of corrupt move that Keye Luke does at the end. Or did I misinterpret what happened?