One of the factors that distinguishes a costumed vigilante from another is their attitude towards crime. Does a caped powerhouse see villains as foe to be bested, in a kind of high-powered sports rivalry? Are criminals more of a societal problem—a sign of a communications breakdown? If you’re Batman, you might see a gun-wielding mugger as a part of something beyond human, a cancer eating away at civilization that can only be addressed with obsessive violence.

Or you could see crime as something beyond even that.

For the Spectre, crime was synonymous with evil—cosmic, spiritual, arisen-from-the-darkest-pit malevolence. And when every problem is the Devil, then every solution is God’s wrath.

For the Spectre, crime was synonymous with evil—cosmic, spiritual, arisen-from-the-darkest-pit malevolence. And when every problem is the Devil, then every solution is God’s wrath.

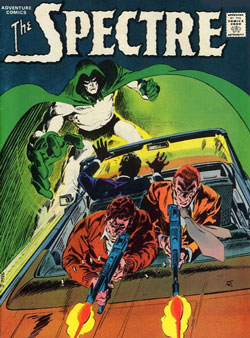

The Spectre predates the vast majority of superheroes currently appearing in comics (and in film and on TV and in games, all of which have become the real home of superheroes in this day and age). He first appeared in 1940, in adventures written by Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel and drawn by Bernard Baily. In this column, I’ve been looking at DC characters with ties to the spirit realm, but the Spectre has the most solid afterlife bona fides of anyone—even more than the Deadman, who’s actually a ghost, or the Phantom Stranger, who hangs out with angels in paradise.

The Spectre wears a cape and hood like the Justice Society member that he is (and almost comically, he also wears trunks, gloves, slippers, and…that’s it), but he’s as much an avenging demigod as he is a superhero. His chief is, or at least seems to be, God, from whom he gets his orders directly. His powers are limitless, though he seems to favor:

- Making himself grow really big

- Bringing inanimate objects to destructive life

- Transmuting bad people into substances such as sand, wood, or glass, which he then righteously destroys.

Like any phantom, he talks with the dead, appears out of nowhere, and can’t be harmed by physical objects. And, he kills with a glance.

All of this makes the Spectre problematic—what kind of challenges can you present to a protagonist who can do anything? But in 1975, editor Joe Orlando brought in writer Michael Fleisher and Phantom Stranger artist Jim Aparo to produce a run of standout adventures for the Spectre that ran in the pages of Adventure Comics. Over a decade later, DC would reprint those stories in a mini-series titled Wrath of the Spectre, the covers of which announced the second go-round for this “controversial classic.”

But, there hadn’t really been any controversy surrounding Fleisher and Aparo’s stories when they first appeared. That’s not to say that the Adventure Comics run didn’t cause a few waves and start a few rumors.

One long-running legend was that the stories were created in response to a real-world mugging: Joe Orlando’s—an event which made the editor so furious that he assigned his writers to create some stories in which thugs weren’t just punished, but mutilated. This, it turns out, wasn’t totally true; Orlando would later say that, yes, he had been mugged around that time, but wasn’t sure when exactly and didn’t remember the mugging as influencing any editorial decisions.

Still, it was in the atmosphere. Films like Dirty Harry and Death Wish were popularizing the idea of a violent crackdown on the 70’s urban crime wave. The Punisher started gunning down bad guys in the pages of Amazing Spider-Man at the same time.

Another rumor was that the run of stories was cancelled before all of Fleisher’s scripts had been illustrated, because a group of writers at DC didn’t like the idea of a caped hero who behaved in such a murderous fashion. Their grumbling made DC’s administration nervous, and they decided that maybe the world didn’t need a superhero who lacked the tiniest shred of mercy.

And violently dispatching no-goodniks is pretty much all the Spectre did. Each issue of the Adventure Comics run had a self-contained story, except for one two-parter. Villains are shown doing heinous things—killing people for money, gassing people (including a little girl) at an auto show as part of some Nazi party extortion scheme, rubbing people out for the mob, orchestrating killing sprees on behalf of mannequins (?) and a museum’s secret diorama collection (!). The killers showed no remorse, and no complexity, though some were pretty bizarre.

Investigating these crimes was NYPD detective Jim Corrigan, who somehow held on to his job despite having what had to have been a zero conviction rate. Corrigan, of course, was the deathless terrestrial form of the Spectre, brought back from the grave after his first assassination (there would be a second) to sort of lend a human set of eyes and ears to the divine wrath of the Spectre and help provide him with targets. Never once do we see Corrigan arresting anyone—all of his suspects are converted to piles of bones, or devoured by boats-turned-into-squids, or otherwise dispatched by a system of justice closer to Abraham’s than the NYPD’s.

And the deaths are spectacular. Fleisher actually had a friend of his help him come up with extremely visual offings. Two of my favorites are a killer who moonlights as a barber getting cut in half by a giant pair of scissors and a mob boss who likes squeaking a little rubber duck getting stuffed into the maw of said duck, made huge and ravenous by our hero.

And the deaths are spectacular. Fleisher actually had a friend of his help him come up with extremely visual offings. Two of my favorites are a killer who moonlights as a barber getting cut in half by a giant pair of scissors and a mob boss who likes squeaking a little rubber duck getting stuffed into the maw of said duck, made huge and ravenous by our hero.

Since an endless parade of brutality does not a 70s comic book make (though that would come in the 90s), Fleisher threw in an improbable love interest, Gwendolyn Sterling, whose wardrobe seemed to be 60% swimwear, and whose two expressions varied between shocked helplessness and lovelorn weepiness.

Gwen is a witness to her father’s assassination in issue #432, and six panels later, she’s asking Corrigan, the detective investigating the killing, if he has a girlfriend. In subsequent issues, she blunders into several psychopath’s schemes, either getting brainwashed or tied up (ropes seemed to be the other 40% of her wardrobe), and the Spectre would save her. During lulls in the cycle of abductions and rescues, she would throw herself at Jim, to no avail.

Gwen was something of a monument to feminine uselessness at a time when female characters and writers were becoming more prominent in the industry. As I’ve mentioned in earlier posts, DC and Marvel were pursuing a female readership with Gothic-style tales, dramatic comics, and female heroes and characters, some of whom would go on to long runs. Gwen may have been something from an earlier era, but then, the Fleisher/Aparo Spectre stories are nods to those original stories from the 1940s. In a weird way, Gwen, a damsel in distress par excellence, fits in perfectly with Fleisher’s deliberately older kind of comic story.

The other era that the stories pulled from is the 50s, specifically the EC crime and horror comics that thrived in the Eisenhower era, before a comics code was established to prevent them from corrupting young minds with tales of degeneracy. Fleisher was conversant with EC’s output, and former EC employee Joe Orlando almost certainly nudged the creative team in that direction.

So what we end up with in those landmark issues of Adventure Comics is a kind of bridge from one time to the next, a crossroads, or a harmonious union. A character from 1940 borrows the flavor of 50s tales, and takes on 70s problems, leading to a revival in the 80s that spawned an excellent 90s run by writer John Ostrander and artist Tom Mandrake.

When I said earlier that 90s comics were endless streams of brutality, the Ostrander/Mandrake Spectre issues were exceptions to that. They established the Spectre firmly in the Judeo-Christian hierarchy (he is revealed to be the angel of the Lord who destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah, and the one who killed the first-born children of Egypt), and the series became an engrossing discussion on the strange nature of justice.

But, back to Fleisher and Aparo—their series delivered everything that was supposed to corrupt the nation’s impressionable youth: violence, carnage, mysticism, amorality—and even sex—and served it in delicious bite-sized morsels. And the most shocking part—perhaps the “controversy” that the 80s reprints alluded to—is that every one of those Adventure Comics issues bore the seal of approval from the Comics Code.

In the distance, you can hear the Crypt Keeper’s mad cackling.

See also: Follow Me into Weird Worlds: DC's Madame Xanadu

Hector DeJean can frequently be found in comic stores, bookshops, and the Eighties. His serialized story of a private detective who only solves food-related crimes is no longer online.