David Goodis was going to be the next Raymond Chandler. In 1946, Goodis’s second book, Dark Passage, was a bestseller and adapted into a classic film noir. Goodis was signed to a studio contract and started making more money than he ever had before. But Goodis never fit into the Hollywood lifestyle. By 1950, he’d moved back into his parent’s house in Philadelphia. By 1967, he was dead at the age of 49.

David Goodis was going to be the next Raymond Chandler. In 1946, Goodis’s second book, Dark Passage, was a bestseller and adapted into a classic film noir. Goodis was signed to a studio contract and started making more money than he ever had before. But Goodis never fit into the Hollywood lifestyle. By 1950, he’d moved back into his parent’s house in Philadelphia. By 1967, he was dead at the age of 49.

Something happened to Goodis while he was in Hollywood. His time in the studio factory inspired the pitch-black novels, which have made him a cult writer among fans of crime fiction. In an earlier post, I explored how Jim Thompson’s time in Hollywood seems to have stifled his creativity and reduced his output. But David Goodis left Hollywood, retreated to Philadelphia, and then really started his career.

Between 1939 and 1950, Goodis wrote four novels including two of his classics Dark Passage (1946) and Nightfall (1947). But from 1950 to 1956, he wrote eleven more novels. Most of these post-Hollywood books are different in tone from what came before. Beginning with 1951’s Cassidy’s Girl, the chance for a happy ending that you find in Dark Passage and Nightfall had been replaced by a hard-edged pessimism.

This pessimism can be seen in Goodis’s characters, but also in his descriptions of a run-down Philadelphia that few writers ventured into. With the exception of brief forays into upper-class Philadelphia, usually with the intention of robbing someone, Goodis’s characters live in a part of the city reserved for “The waterfront bums. The human ruins.” Cassidy’s Girl is set on Dock Street near the Delaware River; Street of No Return is set on Skid Row; The Burglar starts with a heist on The Main Line (a wealthy area outside of Philadelphia) but soon moves deep into the city. Many of these working class neighborhoods don’t exist anymore—they’ve been bulldozed and gentrified. But these run-down neighborhoods hold the key to Goodis’s post-Hollywood work.

In his introduction to the Black Lizard reprints, Geoffrey O’Brien claims, “With the move to paperback originals [post Hollywood], the style and content of the books changed radically. As if mirroring the failure of Goodis’ higher toned literary ambitions, the novels turned decisively toward the lower depths.” It’s not just Goodis’s failed literary ambitions but his failed work in Hollywood that he’s reacting against. As a result, Goodis wrote books about hopeless people, in hopeless neighborhoods. Dock Street is about as far away from Tinseltown as Goodis could get.

This darkness might have its bleakest manifestation in 1953’s The Burglar. Goodis, for the most part, didn’t write about psychopaths; instead, his characters knew what society expected but still chose to act against those expectations. Nat Harbin is The Burglar and occasionally he “came close to envying the people whose lives were based on compulsory directives…so that every morning they had to get up at six or seven, and be a specific place by eight-thirty or nine.”

But of course, Harbin doesn’t envy these working stiffs enough to stop being a burglar. Harbin lives by a different philosophy; he believes that everyone in the world is a thief just like him:

“A fish stole the eggs of another fish. A bird robbed another bird’s nest. Among the gorillas, the clever thief became the king of the tribe. Among men…the princes and kings and tycoons were the successful thieves, either big strong thieves or suave soft-spoken thieves who moved in from the rear.”

All that matters is the next score. The ending of the book shows that it doesn’t even matter if you live, so long as you hold on to what you’ve taken.

In Goodis’s novels, this bleak view of the world is paired with the certainty that there’s no way out—two of his books, after all, are called Street of the Lost and Street of No Return.

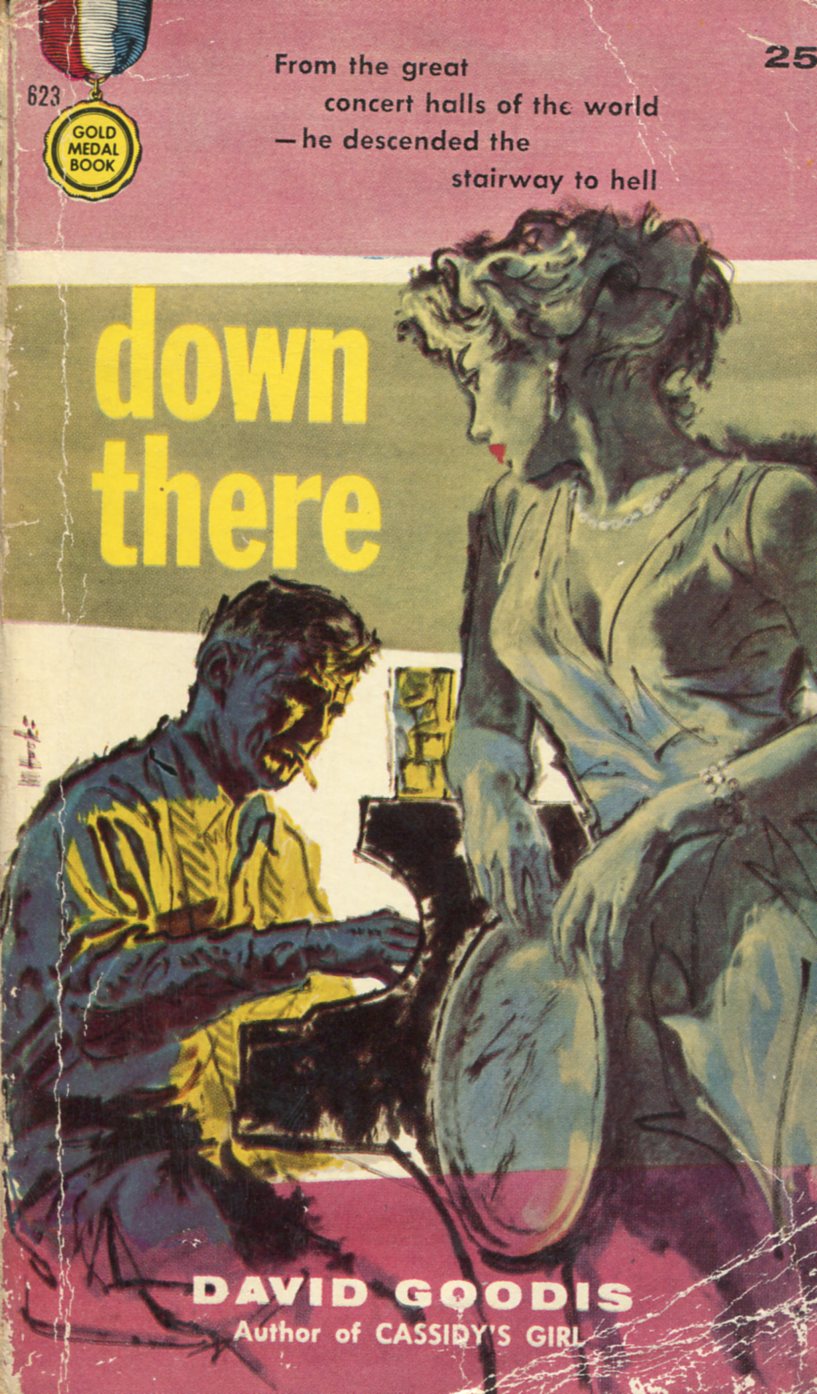

Eddie, the protagonist of Down There (filmed by Francois Truffaut as Shoot the Piano Player) has two secrets in his past. He’s a classically trained pianist who played the most prestigious concert halls in the world. Also, his family is a gang of thieves. But when the novel begins, Eddie is playing piano, under a fake name, in Harriet’s Hut a run-down bar in the Port Richmond area of Philadelphia.

Eddie, the protagonist of Down There (filmed by Francois Truffaut as Shoot the Piano Player) has two secrets in his past. He’s a classically trained pianist who played the most prestigious concert halls in the world. Also, his family is a gang of thieves. But when the novel begins, Eddie is playing piano, under a fake name, in Harriet’s Hut a run-down bar in the Port Richmond area of Philadelphia.

Eddie is a stand-in for Goodis himself. He’s a man who left his neighborhood, was treated like a star for a few years, and now wants to be left alone to punch out his simple creations. Goodis is “playing” for the same crowd that Eddie plays for, “…workers who’d labored hard all week. They came here to drink and drink some more, to forget all serious business, to ignore each and every problem of the too-real too-dry world beyond the walls of the Hut.”

Goodis’s characters don’t leave the neighborhood. They can’t. Shealy, a character in Cassidy’s Girl, speaks words that could have come from the author’s mouth: “‘The dreams again.’ He shook his head with a kind of sorrow. ‘I’ve been here eighteen years and I’ve heard thousands of dreams. And they’ve all been the same. I’m getting out. I’m climbing up.’”

At the end of Down There, a battered Eddie returns to the Hut and sits back down in front of his piano—the reader knows he will never get back up. Goodis was filled with the bitterness of failure, and this pessimism infused all of his work once he left Hollywood, and it prevents his protagonists from achieving their dreams. Today, more than forty years after his death, Goodis is revered by pulp fans. But in his lifetime, he never climbed up.

Images courtesy of Dr. Macro’s and Bill Crider’s Pop Culture Magazine

Richard Z. Santos lives outside of Austin and is enrolled in the MFA program at Texas State University. Once, he worked in Washington, DC, but now he doesn’t do much more than write and teach. He blogs at Paperclip People, and is working on his first novel—a crime thriller set in New Mexico.

Goodis was many things and he liked it that way. In his writing, he was extremely nihlistic, pessmistic, dark and forever in a downward descent. Maybe this is why he appealed to the French so much. The mythos that is David Goodis is alive and well today, however there was so many more facets of this incredibly intuitive writer.

It is quite possible that an author may write a story and that the implications are far greater that the original intent. It is possible that Goodis wrote beyond his own plot and desire to spin a tale. Primarily, he was a story teller. Once he began, his stories fell in place. It never occurred to him that the people—his people, were personae or archetypes and that when he had completed a work there was anything more to do—certainly not in terms of intellectualizing or submerging for hidden philosophic treasure.

His art mirrors a part of truth—that man is alone. His violence perhaps a syndrome of our human condition.

Thanks Lou–you’re right, he’s a powerful writer and a real master. I think “Nightfall” is an interesting exception to his darkness though. Sure the novel’s pretty bleak at times but it has pretty happy/resolved ending. Although that book was written early in his career–just before Hollywood and success.

I’ve read a few Goodis books, and didn’t realize Philadelphia was such an element. And I loved Dark Passage! I want to go back and revisit what’s on my shelves now. Thanks.

“[url=http://www.definitions.net/definition/Home]Home[/url] is where you [url=http://www.definitions.net/definition/come]come[/url] to, when you run out of places.” Barbara Stanwyck expressed it with a hard-edged bitterness in Clash by Night.

The streets of Philadelphia were a roadmap to his soul. It’s the home to where Goodis ran, to where he thought he might find himself. And so he did, as evidenced by his books and soon after, by his death.

Excellent article. David Goodis deserves to be more widely known and appreciated than he is. His cast of characters and the streets of Port Richmond are at the very heart of the noir aesthetic. My own attempt at noir is set in Port Richmond,’ purely as a homage to David Goodis.

*an homage.

I believe there is a small David Goodis museum or bookstore in Port Richmond that can be visited by appointment.