The demand for a follow up proved too great, however, and Leone consented to make another Western. The film he made was Once Upon a Time in the West, and it would prove to be a culmination of everything he thought about the genre.

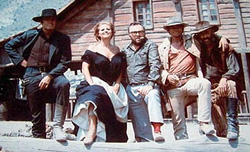

At a deliberately paced (read: slow) 168 minutes, it’s an epic. Set around the fictional town of Flagstone, Arizona, the story follows the fortunes of four main characters: Jill McBain (Claudia Cardinale), a woman who has just arrived in the region to join her new husband, only to find that he and his children have been murdered; Frank (Henry Fonda) a ruthless assassin working for the railroad; Cheyene (Jason Robards) a notorious bandit who might have a better heart than his reputation suggests; and a mysterious unnamed gunman (Charles Bronson) who says so little and spends so much of his time blowing mournful airs on his harmonica that the other characters dub him Harmonica. In true Leone fashion, these characters circle each other wearily, with partnerships made and broken and passions running from hot to scorching.

Yet it is a fascinating reworking of the Western. The cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard called Leone the first “postmodernist film director” for a reason. By the ’60s, the Western had been around for the better part of sixty years. In the ’40s and ’50s, it ruled both the box office and the new medium of television. Week in and week out, the silver screen and the boob tube released an unceasing series of cowboy stories. By the time Leone took it upon himself to make a Western, the genre had exhausted itself. It wasn’t just that everyone in the world had already seen shootouts on dusty streets, it’s that everyone had already seen literally thousands of shootouts on dusty streets. The Western was still personified by John Wayne, but Wayne was old and fat and wearing a toupee. Whatever claim to authenticity the genre had once possessed had long since disappeared. The Western was now clearly a myth, and for a myth to live it needs to move, to absorb new influences and update itself in light of the new society through which it will pass.

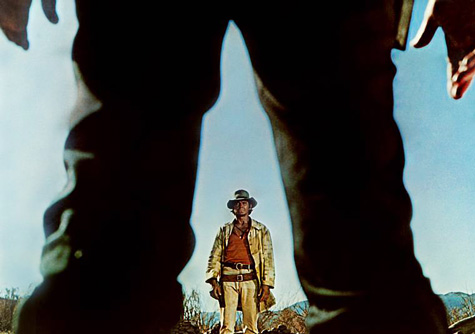

With all his films, but particularly with Once Upon a Time in the West, Leone turned the Western into a universe of dread. The dominant feel of most American Westerns was liberation, the expanse of the topography embodying the expanse of the human spirit. The dominant feel of this film, however, is fear. Leone’s open spaces don’t inspire wonder, they inspire agoraphobia. Every scene in the film seems to be leading into some act of violence, whether it is or not (and most of the time, it is).

The film fundamentally reconfigures the meaning of Western iconography. The best example of this is the stunning performance by Henry Fonda as the heartless killer Frank. By 1968, Fonda was an icon on par with Stewart and Cooper, a man who had played Wyatt Earp and Abraham Lincoln to great acclaim. Leone was smart enough, though, to grasp that the essence of Fonda was discomfort. Beneath his Midwestern politeness, Fonda was taciturn and aloof, and beneath that emotional distance was a reservoir of anxiety and pain.

Leone placed him opposite Charles Bronson, the harmonica-playing gunfighter who is hunting Frank for some evil done in the past. Bronson is an interesting case study, a man who had been supporting help in movies for a long time (do not miss his turn as the jeering, beefy thug in the noir classic Crime Wave) before finally hitting it big in his middle age in The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape, and The Dirty Dozen. He’s never better than in Once Upon a Time in the West, though, where Leone uses his face like one of the rocky spires in Monument Valley. Watching his showdown with Fonda at the end of the film is like taking a lesson in the essence of movie persona. Bronson is as wholly self-contained as a rock. Fonda, never once seeming to reach for the effect, is jittery, his blue eyes telegraphing the disquiet of a man with a soul bound for hell.

Leone placed him opposite Charles Bronson, the harmonica-playing gunfighter who is hunting Frank for some evil done in the past. Bronson is an interesting case study, a man who had been supporting help in movies for a long time (do not miss his turn as the jeering, beefy thug in the noir classic Crime Wave) before finally hitting it big in his middle age in The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape, and The Dirty Dozen. He’s never better than in Once Upon a Time in the West, though, where Leone uses his face like one of the rocky spires in Monument Valley. Watching his showdown with Fonda at the end of the film is like taking a lesson in the essence of movie persona. Bronson is as wholly self-contained as a rock. Fonda, never once seeming to reach for the effect, is jittery, his blue eyes telegraphing the disquiet of a man with a soul bound for hell.

The rest of the cast is excellent. As Jill McBain, Claudia Cardinale gives the film its heart, and as Cheyene, Robards gives it its wit. Cardinale was a bombshell in 1968, and her beauty and sensuality are, it is safe to say, worshipped by Leone’s camera. (Though it should be noted that he gives the same attention to the craggy faces of Bronson, Fonda, and Robards). But Cardinale is not simply window dressing here. She’s by far the most fully realized female character Leone ever put onscreen. At one point, she tells Robards defiantly:

“If you want to, you can lay me over the table and amuse yourself . . . No woman ever died from that. When you’re finished, all I’ll need will be a tub of boiling water, and I’ll be exactly what I was before—with just another filthy memory.”

Robards tells her later, “You know, Jill, you remind me of my mother. She was the biggest whore in Alameda and the finest woman that ever lived.”

Leone set out with this film to make his grand statement about the Western. Holing up with his co-writers Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento, he re-watched classic Westerns with studious intensity—paying particular attention, according to film historian Christopher Frayling, to Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar and Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon. He shot his film in the deserts of Almeria, Spain, and then came to America to shoot some scenes in Monument Valley, deliberately linking his film to the Westerns of John Ford. The result is a film that is at once a Western and also a complete disruption of everything we expect from the Western.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of Hell on Church Street.

PS. The film is available for Instant Watch on Netflix, but the special features on the DVD and Blu-Ray editions of the film are packed with good stuff for film geeks. Well worth checking out.

“His greatest strength was his ability to stand in front of the camera and just be.”

That’s Frank Langella on Robert Mitchum, but I think it’s true of Bronson as well.