Before we go further, I should pause to declare something: I am a proud partisan of Orson Welles. No one doubts Welles’s talent, but there is a prevailing opinion in some circles that he died a fallen, undisciplined wunderkind. He made Citizen Kane, the story goes, and the rest was a sharp drop.

Bullshit, I reply.

Welles is one of the cinema’s greatest artists. I agree with the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum who suggests that Welles is fundamentally misunderstood when he is considered as a failed Hollywood filmmaker. In reality, Rosenbaum argues, Welles was an avant-garde filmmaker who made some of his films in Hollywood. He is the anti-professional, the anti-Robert Wise. I love Wise, and I love Welles, but comparing them is apples and watermelons.

I’ve yet to talk about the plot because, as I said, with Welles one must always begin with the actual picture. The director never simply photographs plot points. With Welles, the texture of the picture—the movements of the camera, the detail of the sets, the grotesquery and beauty of the faces—all of it, is absolutely integral to the movie. This makes him a challenging artist in many ways, of course, but it is what also makes his movies an essential part of cinema.

Having said that, The Lady from Shanghai does have a tangled plot, though it is difficult to gage how much of this tangle is by design, by mistake, or the result of the hatchet job editor Viola Lawrence did at the behest of Columbia chief Harry Cohn after Welles was kicked off the picture. One distinctly feels the absence of the missing half-hour of the film that was cut, as though the editing is purposely bad. A case in point are the opening scenes of the film. Welles shot the opening sequence in three long takes (akin to the long opening take in Touch of Evil), but they’ve been chopped up, truncated, and spliced together in a confusing muddle. It’s impossible to believe that anyone seriously thought that the editing job actually made these scenes flow better.

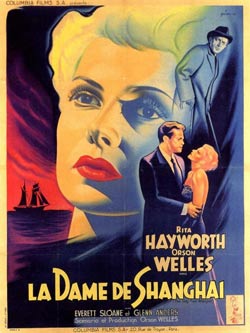

Still, after the first couple of scenes, the plot begins to take shape. Welles plays Michael O’Hara, an Irish seaman who hires on to pilot the yacht of a rich criminal defense attorney named Arthur Bannister (an excellent Everett Sloan) in order to be close to Bannister’s beautiful wife Elsa (Rita Hayworth). They sail around South America to San Francisco and along the way are joined by Bannister’s oddball law partner George Grisby (Glenn Anders, in the film's most bizarre performance). Grisby corners O’Hara and offers him five grand to commit a murder. Michael, needing the money to run away with Elsa, accepts.

One of the fascinating things about this movie is that Michael accepts this offer knowing fully that he is going to get screwed. The entire movie, designed that way, plays like a turbulent memory. O’Hara narrates the picture and tells us from the outset that it’s about him making a fool of himself for Elsa. He tells us this again as the plot progresses, and by the end all he can tell us is that he’s trying to forget her and “Maybe I’ll die trying.”

Good luck, pal. Elsa is played by Rita Hayworth, sporting short blonde hair. The film was infamous at the time because Welles had the audacity to cut and dye Hayworth’s famous red locks, but Hayworth looks gorgeous. She gives a good performance, though I suspect that in the original cut Elsa was a colder yet ultimately more interesting character. The last few minutes of the film are justly admired because they are a visual tour de force, but once again, one feels the loss of Welles’ missing footage. The funhouse sequence that culminates in the famous shoot out in a hall of mirrors was much longer in the original cut of the film. Here, we get only a hint of the surrealist nightmare envisioned by the director. Likewise, we only get a sense of what Welles was trying to do with the story. There’s dialog between Welles and Hayworth at the end of the film that references conversations we haven’t heard but were clearly supposed to have heard.

There is the heartbreaking bargain you have to make with Orson Welles. Much of his work—more than that of any other major director—comes to us in damaged shape. His best films (Citizen Kane, The Trail, Chimes at Midnight, F for Fake) are uncompromised, but more often than not his movies were taken out of his control and sullied by lesser talents. When you consider that he was making difficult films to begin with, the full picture begins to emerge. A movie like The Lady from Shanghai is entertaining, challenging, and teems with the brilliance of its maker, but it is incomplete, like a pulp Venus de Milo. Viola Lawrence was a perfectly good editor (she edited In a Lonely Place), but as many times as I have seen this movie I can never shake the feeling that the masterpiece it might have been ended up on the floor of her cutting room.

Jake Hinkson is the author of several books, including the novel The Big Ugly, the newly-released short story collection The Deepening Shade, and the essay collection The Blind Alley: Exploring Film Noir's Forgotten Corners.

Read all of Jake Hinkson's posts for Criminal Element.

PS. Fun fact: one odd side effect of this film is the theory, put forward in the book Childhood Shadows: The Hidden Story of the Black Dahlia Murder by Mary Pacios, that Orson Welles killed Elizabeth Short, aka The Black Dahlia. Pacios reads The Lady From Shanghai--and especially the crazy funhouse sequence–as a kind of veiled confession.

It is extremely likely that Orson Welles put in that film actual footage of Elizabeth Short’s torture, murder and mutilation. It should be noted that was a registered Mortuary Assistant, having recently obtained the documentation, needed. The homicide detectives always had problems trying to find the blood and gory bits, that would only have been easy to dispose of at a mortuary.