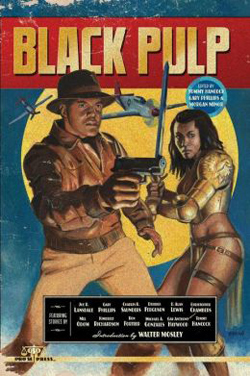

Black Pulp is a collection of stories featuring characters of African origin, or descent, in stories that run the gamut of genre fiction. A concept developed by noted crime novelist Gary Phillips, Black Pulp brings bestselling authors Walter Mosley and Joe R. Lansdale, Gary Phillips, Charles R. Saunders, Derrick Ferguson, D. Alan Lewis, Christopher Chambers, Mel Odom, Kimberly Richardson, Ron Fortier, Michael A. Gonzales, Gar Anthony Haywood, and Tommy Hancock together to craft adventure tales, mysteries, and more, all with black characters at the forefront.

Black Pulp is a collection of stories featuring characters of African origin, or descent, in stories that run the gamut of genre fiction. A concept developed by noted crime novelist Gary Phillips, Black Pulp brings bestselling authors Walter Mosley and Joe R. Lansdale, Gary Phillips, Charles R. Saunders, Derrick Ferguson, D. Alan Lewis, Christopher Chambers, Mel Odom, Kimberly Richardson, Ron Fortier, Michael A. Gonzales, Gar Anthony Haywood, and Tommy Hancock together to craft adventure tales, mysteries, and more, all with black characters at the forefront.

“Drums of the Ogbanje” by Mel Odom is a zombie pirate adventure from the anthology Black Pulp, edited by Tommy Hancock, Gary Phillips, and Morgan Minor (available May 6, 2013).

1. Moonlit Steel

Bay of Luanda

West Africa

1825

With a heavy fighting knife clamped between his teeth, Ngola Kilunaji climbed the thick anchor rope up the ship’s hull to deliver death to Portuguese slavers.

The vessel tugged against its anchor, riding restlessly atop the white-topped waves. Dark clouds obscured the full moon as they scudded across the sky, promising a squall by morning or shortly thereafter if the thick air was any indication.

Ngola felt the coming change of weather in the old whip scars that striped his back. The sour stench of human misery clung to the vessel, hammered into the ship’s timbers, made part of the ship by blood and death. More than that, though, Ngola’s nostrils took in the sick scent of hopelessness.

At the gunwale, he paused and listened. Voices drifted on the breeze, snatches that were ripped apart on the wind. He understood Portuguese well enough, though he spoke English and French much better. Instead of being bored, the sailors sounded ill at ease.

“I do not trust that old man, Luis. I think he is going to bring down some heathen curse on us with everything he is doing.”

“Captain Salazar will not allow that to happen. He will kill Lukamba first. Just be glad that that old demon worshipper is gone from the ship.”

The names stirred a memory within Ngola. Though their paths had never before crossed, Ngola had heard the whispered stories of the old witch doctor and of the greedy Portuguese captain who hunted lost treasures as well as slaves. The dead were supposed to walk at Lukamba’s command, and demons were allowed entrance to the world through his knowledge of the dark magic that was Africa.

“Salazar is hypnotized by Lukamba’s tales of treasure. The captain dreams of riches. Instead of chasing myths and lies, he should be thinking of the money this cargo of slaves will bring us. After we deliver these wretches to the Caribbean, we will have wealth enough to keep us in rum and women for days. Then we can return here for more slaves and begin again.” The man cursed. “Instead we are here while that old man leads the captain after ghost ships and searches for more of his evil vodun spirits.”

“Pray that those spirits take Lukamba to hell and drive the captain back to us. Or maybe take the captain as well and that Carneiro becomes the ship’s master. I would follow him.”

“Careful, you fool! There are many here who like Salazar and dream of the same riches he does. If they hear you, they may tell Salazar, and then you’ll end up at the bottom of the sea.”

“Faugh! Were he to find those riches, you know that precious little will trickle down to the ship’s crew.”

Glancing back down the anchor rope, Ngola spotted Colin Drury only a few feet beneath him. The Irishman held steady, his face grim and determined as his pale blue eyes blazed in the light from the lanterns hanging at the stern. Below Drury, three more men, two Africans and an Englishman, held onto the rope as well. Seven more men bobbed in the water, waiting their turn at the rope. Ngola’s ship lay a quarter-mile away to the north, black against the backdrop of the tree-covered coastline.

All of the men were proven warriors, used to boarding ships and fighting with edged steel. They’d been handpicked by Ngola and blooded again and again against the Portuguese and the tribes who took slaves.

Ngola swarmed up the rope and heaved himself over the side, landing on callused bare feet. He had to protect his men as they came on board and he knew their presence would not long be secret. On the deck, the wind whipped over him, cooling the wet pants against his skin.

He fisted one of the cutlasses hanging at his hip and drew it from its leather sheath with a thin whisper. He put the knife in the sheath at his back and took up the mambele from his other hip, unhooking it from his second cutlass.

The mambele throwing dagger looked like a falcon’s claw, providing a total of three blades and an excellent chance of sinking deeply into its target. The heavy weapon looked unwieldy, but in Ngola’s hands it was lethal and swift as a diving hawk.

Colin Drury stood beside Ngola on the stern deck. Although the Irishman was only a couple inches short of six feet, Ngola loomed over him. Where Drury was compact and lean and pale, Ngola was broad and thickly thewed with ebony skin. Drury wore his hair pulled back in a queue and went clean-faced. Ngola’s bare head gleamed in the lantern light. Water droplets clung to his short, curly beard.

Footsteps padded over the wooden deck, heading for the stern. Ngola flowed into motion, shifting from stillness to action in a single lithe stride. Behind him, Drury stood watch over the anchor rope as their men kept boarding.

Three Portuguese sailors crossed the main deck below and headed toward the stern castle where Ngola was. Knowing there was no way his men would escape notice and that a cry of alarm would be short in coming, Ngola decided to take advantage of their brief edge of surprise. Weapons in hand, he launched himself at the three men while they were still engaged in their argument about the ship’s captain and the certainty of vodun curses.

Ngola smashed into the men, knocking them all sprawling across the deck. Heaving himself up on one knuckled fist, Ngola set himself and swung the cutlass at his nearest enemy. There was no mercy in his heart. The men were slavers and Ngola had sworn to kill as many of them as he was able.

The heavy blade of the cutlass smashed through the slaver’s skull as much as it sliced. The dead man spilled away when Ngola yanked the blade free. One of the other men came up quickly, lashing out with a long fighting knife rather than trying for his sword.

The move almost caught Ngola off-guard. Reflexes honed by years of fighting for his life in Haiti during the slave uprisings against the French, then more years on a ship in Lord Nelson’s Navy battling still more French spurred Ngola to lift the mambele to intercept his opponent’s knife.

Razor edged metal screamed as the blades met, but the knife stopped inches short of Ngola’s throat. The Portuguese slaver’s eyes widened in fear, then emptied of life when Ngola split the man’s skull with his cutlass.

With an oath, the dead man’s blood spattered across his bare chest, Ngola kicked the corpse from his blade and shook the trapped blade from the mambele. The other two slavers recovered quickly and shouted in alarm as they drew their weapons.

Colin Drury fell in beside Ngola, adding his blade to his captain’s as they battled the two slavers. Swords clashed and the clangor of metal swelled over the ship and the nearby waves. More Portuguese slavers poured from the ship’s hold with weapons in their hands, crying out for their brothers to rouse and follow them into battle.

The slave ships usually kept a crew of thirty to forty sailors. Once chained in the hold belowdecks, the slaves didn’t offer much resistance. And every man over what was needed was another mouth to feed and less space for cargo. But Salazar was an aggressive captain and kept extra men to crew a British ship if he had the chance to take one as a prize in battle. The Portuguese vessel had already taken two ships from captains in the West Africa Squadron, the small fleet the British Empire had sent to combat the slave trade.

Ngola blocked an overhand blow that streaked for his head, catching his opponent’s cutlass with the mambele. The blades clanked as they clashed. Holding the blade trapped, Ngola went chest-to-chest with the man. The Portuguese slaver’s fetid breath reeked of decay as it sprayed over Ngola’s face.

Then Ngola smashed his forehead into the man’s nose, shattering the vulpine beak and sending the slaver stumbling back. A quick slash of the cutlass spilled the man’s guts across the deck, drenching the dry wood in blood.

Ngola’s crew spread out behind him, taking up fighting positions, but they were being pressed hard by the thirty Portuguese slavers filling the deck in front of them. Lantern light danced along the naked blades.

“Joao!” Ngola roared.

“Aye, Cap’n!” Slight and wiry, the young man fought at the fringes of the crowd. He was of mixed blood, his mother a slave and his father a Portuguese rapist he’d never met and had sworn to kill. The young sailor was handsome and had hazel eyes that belonged on a large cat.

“Charge that blunderbuss!” Ngola commanded. “Let’s cull these dogs.”

“Aye, Cap’n.” Joao swung his cutlass in a savage slash that cleaved into the side of a slaver’s head and dropped him mewling to the deck. Instantly, Joao spun and retreated to the stern castle while Mamadou and Kayode shifted to cover his back.

On the stern castle, Joao unlimbered the short muzzleloader he’d carried in a watertight sleeve over his shoulder. He readied the weapon in short order and dropped to one knee, bringing the blunderbuss to his shoulder. Less than two feet in length and near big around as Joao’s wrist, the thick barrel gleamed like it was covered in dark oil.

“Ready, Cap’n!”

Parrying two blades at once with his cutlass, slashing the throat of the third man with the mambele, Ngola raised his voice. “Give ground!” He disengaged from the slavers he swapped parries with and took two steps back.

Instantly, his crew did the same, displaying the discipline he had trained into them.

For a moment the Portuguese slavers held back. Bloodied and caught unprepared, they hesitated at stepping over the bodies of their own dead to attack.

“Fire!” Ngola shouted.

The blunderbuss’s frizzen struck sparks that ignited the black powder on the flash pan. An instant later, the weapon detonated with a sonorous BOOM! and belched forth bronze balls and a cloud of swirling gray smoke.

The projectiles smashed into the front line of the Portuguese and cut them down, sending the luckless men stumbling back into their fellows with their faces shattered in and their hands missing fingers, their arms broken and bloody.

“Reload!” Ngola yelled.

“Reloading, Cap’n!”

Ngola stepped forward, giving his hated enemy no quarter as he swung his heavy blade, removing a man’s weapon along with his hand. “Advance!” His crew moved with him, slashing out at the stunned Portuguese.

Though the slavers were shell-shocked and bloodied, they fought for their lives. At Ngola’s side, Ikenna dropped with a ball in his brain, and at the end of the line Corporal Horace Dinwiddy, lately of the West Africa Squadron, went down from too much blood loss from his wounds.

Losing both of the men saddened Ngola because he knew them well, as he did all of the men that sailed under his command, but he pushed the emotion away. There would be time to grieve later. Now was the time to fight. He slid the mambele into the sheath at his back.

Reaching down as he blocked the swing of a cutlass with his own, he fisted a pistol in his left hand, drawing it from the dead man at his feet. He eared the hammer back, shoved the muzzle into the mouth of the slaver in front of him, breaking the slaver’s teeth, and pulled the trigger.

The ball exploded through the back of the slaver’s head and into the face of the man behind him. Squalling in pain, not dead but maybe dying, the second slaver fell backward, taking one of his mates with him.

Ngola used the pistol to block another blade, then dodged to the left, bumping into Colin Drury for an instant as another slaver fired his weapon. The ball whipped by Ngola, leaving a trail of heat that kissed his cheek lightly. Blocking another man’s blade with his cutlass, Ngola used the pistol like a hammer, swinging it with all his strength into his opponent’s face.

The man’s forehead cracked open under the impact and blood ran into his eyes as he dropped. Dead, dying, or unconscious, the man would not soon return to the fight if at all.

“Ready, Cap’n!” Joao called.

Quelling the blood lust for battle that filled him, Ngola forced himself to order the brief retreat. “Give ground!”

Again, his men stepped back. Another of the men had fallen, but Ngola couldn’t tell who it was yet. At the command, the Portuguese slavers knew what was coming this time and most of them tried to flee. Two of them, however, lifted firearms.

Ngola plucked the mambele from its sheath, set himself, and whipped the dagger forward. The multi-bladed weapon spun through the air, splintering the unsteady lantern light as the ship rocked at its anchors, then buried in the chest of one of the men holding a leveled pistol. Instead of firing his weapon, the man stood transfixed and stared down at the knife that had split his heart.

“Fire!” Ngola ordered.

The blunderbuss exploded again. Caught by the fringe of the blast, the second slaver with a pistol went down. The bronze balls chewed through the retreating pack of men.

“Reloading!” Joao sang out.

“Advance!” Ngola strode forward and grabbed the dead man’s fallen pistol.

The Portuguese hadn’t stopped running toward the ship’s prow. The slaver took brief aim with the pistol and fired, not waiting to see the effects of his shot. Ngola fired his pistol and the ball caught the fleeing man in the back of the neck, pitching him forward in a heap.

Placing a foot on the dead man with the mambele in his heart, Ngola yanked free the blade and led the charge after their foes. Overwhelmed, the Portuguese fell in short order. A few dove over the side into the sea.

“Get the lanterns!” Drury ordered, seizing one from the railing himself, then grabbing a pistol from a dead Portuguese.

The Irishman held the lantern up and out over the ship’s side. He steadied the pistol, his face lean and hard and merciless. He, too, bore scars from the slavers, and not all of them showed on his body. He had lost good men and several friends when the ship he’d served on had gone down to the Portuguese.

The pistol cracked in Drury’s fist and the ball sped true, punching through the head of the slaver swimming for the coastline. The man stopped swimming and went slack as oily blood slicked the ocean’s surface. The corpse floated in the water till a triangular fin cut toward him. The dead man disappeared a moment later, then a severed arm floated to the top.

Gray smoke plumed Drury’s head, and his grim satisfaction made Ngola think he must resemble a demon from the Christian Hell. Drury turned with a grin to face Ngola. “Fancy that. We were swimming all that way with sharks in the water.”

“Would you have stayed back if you had known?”

“Of course not.” Drury knelt and found powder and shot on the dead man. “But I might not have been so carefree in doing it.”

More sharks fed on the hapless Portuguese, yanking them down into the dark water. The sailors who knew how to swim didn’t know which direction to head. Ngola’s men fired at them as soon as they could find or reload weapons. The sharks steadily seized their prey, the living and the dead.

“Later, when we tell this story over grog, you and I will swear that the sharks swam with us,” Drury said.

Ngola grinned, then scoured the ship’s deck. He sheathed his mambele and lifted powder and shot from the nearest dead man, then reloaded the pistol he’d picked up. He nodded at Drury. “Bring your lantern. Let’s go see what awaits us belowdecks.”

Seeing men, women, and children shackled in the bowels of a slave ship was something Ngola had never gotten used to. He wasn’t looking forward to repeating the experience. He took a fresh grip on his cutlass and headed for the nearest hatch, stopping only for a moment to take a ring of keys from one of the dead Portuguese.

As he neared the opening, Ngola opened his mouth and breathed through it instead of his nose. The stench wasn’t so bad that way. Nothing would ever make it bearable. Despite the hard way many of the Portuguese sailors had died under the blades of his men, Ngola had no mercy in his heart for his enemies. If any yet lived, he would slit their throats.

He stepped down into the hold.

2. The Scorpion

The foul, fetid air that closed in on Ngola below the ship’s deck felt heavy and oppressive. He resisted the urge to cut through it with his cutlass as Drury lifted the lantern to shine down into the hold.

Murmurs and whispers echoed in the confined space. Frightened eyes stared back at the lantern.

No matter the number of horrors and degradations he’d seen in Africa, on Haiti, and while serving in Lord Nelson’s Navy, Ngola knew that he would never get used to seeing people stripped of their humanity as they were in that hold. Scores of men, women, and children lay bound by chains and dressed in filthy rags. Their helplessness tore at Ngola. He forced himself to be strong, knowing that most of them would be saved through his crew’s efforts tonight.

And they would be given back their freedom.

“My God,” Drury said hoarsely.

Slowly, Ngola sheathed his cutlass, then spread his hands out before him, showing their emptiness. He spoke in Portuguese, which most of the coastal people had some experience with, though most of that was unpleasant.

“We mean you no harm. We are here to free you.” He repeated the words in English and French, then as best as he could in the half-dozen dialects he knew from the areas he had traveled through.

Many of the men and women wept with relief and gave thanks to their gods and ancestors.

Standing in front of them, Ngola’s memories of masters and whips and chains rolled through his thoughts. Sold into slavery as a child, impressed by the British Navy as a young man, he had been free for the last seven years, and he knew he would never serve a day as a slave again. He would die first, with an enemy’s blood in his teeth.

Kneeling, Ngola used the keys he’d taken from the dead Portuguese slaver to open the locks holding the nearest, strongest man. He offered the man his hand and pulled him to his feet, then began on the next lock.

Hanging his lantern on a nearby crossbeam, Drury called for more of the sailors above, then fell to opening the locks on chains as well. The heavy links smacked against the deck again and again as they worked.

A small girl only nine or ten years old wept and shivered and drew away from Ngola as he approached. Bloody sores at her wrists and ankles showed where the iron cuffs had worn at her tender flesh.

“Easy, child.” Ngola’s voice rumbled softly as he reached for her chains. “I will not harm you.” He hated the fear that he saw in her dark eyes, but he twisted his lips into a reassuring smile.

She trembled as he released her, then got up and ran to the back of the ship, screaming for her mother. A woman reached for the girl and took her into her arms. Both of them cried and wept as they clung each to the other.

For a moment, Ngola thought of his wife and of their son. At times on Mambele, he considered putting down his sword and living with Kangela in her village, and of giving up his battle against the slavers. He hated being away from his family. But just as the scars on his back and his wrists and ankles would never fade, nor would his desire to fight those who subjugated others. As long as the Portuguese and others took slaves, he knew he would seek them out and kill them.

He focused on the task at hand and reached for another lock.

“Ngola!”

The man’s voice was dry and thin, only brushing against Ngola’s ears. Ngola rose from his crouch and stared into the darkness at the end of the ship. His hand rested on the hilt of his cutlass. “Who calls my name?”

“I do.” A thin arm rose from near the stern.

Ngola took the lantern Joao handed him, then gave the younger man the key ring. Holding up the lantern, Ngola walked toward the stern till he reached the man who had called for him.

The man was old and withered, gray with sickness. He looked up at Ngola and spoke in a croaking voice. “Do you know me?”

The man’s features were familiar, but it took Ngola a moment to summon a name. “You are Olufemi. You are of my wife’s tribe.”

Though Ngola had lived sporadically among his wife’s people for six years, and her people didn’t feel comfortable around him, he had gotten to know a few of them. Eight years ago, he’d almost been killed in an attack on a Portuguese fort and escaped into the jungle, more dead than alive. Since his recovery and his marriage to Kangela, he had not mixed with the tribal people on a regular basis. Their ways were not his, and he had never quite been accepted among them. Ngola would always be known as an outsider among them. He had not made many friends even though they knew he fought the Portuguese. His wife’s people also hated him for taking their young sons to crew his ship. Many of those young men did not return, either because they were dead or because they wanted to see the world.

“I am Olufemi. My wife is aunt to your wife’s father.”

Ngola thought he might have known that, but the familial relationships among the tribe were too many and too complicated to keep track of.

“What are you doing here?”

“The slavers attacked our village.”

A chill passed through Ngola and he held the lantern up high so he could survey the nearby faces. His heart sped up as he realized he recognized at least a dozen more people from Kangela’s tribe. He didn’t see her there, nor did he see Emeka, their son. But his relief was washed away by the old man’s next words.

“The slavers took Kangela, Ngola, and they have your son too. Lukamba ordered that they be brought along with the shore party to look for the captain’s treasure. And the demons Lukamba seeks.”

Olumefi sat on a stool on the ship’s deck. The fresh air seemed to do the old man some good, as did the bread and wine Ngola had one of his men bring from the ship’s galley.

Ngola struggled to keep himself calm, forcing himself to think when every fiber of his being demanded that he set sail to the coast to begin looking for his lost family. He clung to the belief that Kangela and Emeka were still alive, but knowing they lived to become prey for Lukamba almost unhinged Ngola.

“The slavers came to our village four or five days ago.” Olufemi shook his head. “I think I have kept track, but I cannot say for certain how much time has passed.” He sipped wine from a bottle. “Captain Salazar came among us looking for you.”

“Me?” That surprised Ngola. He was careful to leave no trail back to the village, which was farther inland than many of the Portuguese traveled. Normally they depended on the African tribes that dealt in slavery to sell prisoners into chains.

“Yes.” The old man nodded. Pain showed in his rheumy eyes, but it wasn’t from his current physical distresses. “Someone in the village told the Portuguese captain that you lived among us.”

“Who did such a thing?”

“I do not know. I have heard that whoever gave the slaver captain the information did so for gold, or revenge over a son that was lost to your crew and never returned.”

Ngola said nothing. He had the blood of several of the tribe’s young men on his hands, and there was no way he could dispute that.

“The slavers came in the dead of night. We had no chance for escape. Your wife fought bravely, but they captured your son. Once the Portuguese had Emeka, Kangela surrendered.”

Ngola breathed in, forcing himself to listen.

“You should have seen her, Ngola. She killed two of the men before she surrendered, and she would have killed more.” The old man looked proud, but the fearful sadness quickly shone again in his eyes. “There were men among the slavers that would have murdered her for those that she killed, but Captain Salazar stayed their hands.”

“Where are they now?”

The old man waved at the darkened coastline to the east over the prow. “There. While the slavers took prisoners from the village, Lukamba killed Uzochi and raided his house.”

Uzochi was the tribe’s houngan, versed in the ways of the vodun spirits and the art of healing.

“Lukamba searched among Uzochi’s belongings and took from them the medicinal roots and fetishes the houngan had made. Among those things, Lukamba found a map.”

“What kind of map?”

“I do not know. I only heard this, and saw that Captain Salazar was at once interested. I heard a Portuguese ship’s name mentioned. Escorpiao.”

Drury glanced at Ngola. “The Scorpion?” He shook his head. “That ship is a myth, Ngola, a tale that is told by men with wine to drink and time on their hands.”

The Scorpion had supposedly sailed West Africa over a hundred years ago. Captain Antonio de Cardoso had gotten rich from the slave trade, then he had vanished. Some said that he had sunk at sea, weighed down by his riches, or that a tentacled water demon dragged him below the waves.

Others insisted that de Cardoso had sailed up a West African river to hide his treasure.

“Perhaps the tale of The Scorpion is only a legend.” Ngola stared at the shadow-filled coastline. “But there is where Captain Salazar has gone, so I will follow.”

Clad in boots and a thick cotton shirt to blunt the wind’s cruel teeth, a brace of pistols slung across his chest, Ngola clambered down the side of the ship to the waiting longboat. His pulse beat at his temples even though he was certain his heart must have stopped in his chest.

Eight of his men sat ready at the oars, all of them armed to the teeth. Joao crouched in the stern to man the tiller. The wind came out of the west and blew toward the dark coast a quarter mile to the east.

Before Ngola could take his place at one of the oars, Drury dropped down into the longboat beside him. Ngola looked at his friend with displeasure. “You’re not coming.”

Drury’s eyes narrowed and he shook his head. “I’m not staying, mate.”

“Someone has to remain with Mambele.” Ngola’s ship had sailed nearer, only a stone’s throw from the slave vessel.

“I put Olamilekan in charge of the ship.”

“Olamilekan is not a captain.”

“He is till we get back.” Drury sat on the bench on the other side of Ngola.

Anger and uncertainty rolled in Ngola’s belly like coals. “I do not want to lose my ship.”

Drury returned Ngola’s gaze full measure. “You don’t want to lose your wife and son, mate.” He put a hand on Ngola’s shoulder. “You need me. And if you don’t, then Kangela and Emeka do. I’m not going to hang about and hope for the best.” He took a breath and picked up his oar. “Now…are you going to argue some more? Or are we going to go save your family?”

Feeling the power of the sea as he braced himself and flexed, Ngola pulled the oar with even strokes. All of the longboat’s crew did. At one time or another, they had all been sailors or slaves. Most of them had been both.

The longboat rose and fell with the waves that rolled in to the coast. The prow cleaved the white caps.

Ngola shook his head and concentrated on his rowing. Each pull took him closer to the coast, closer to his family…and closer to the men he would kill.

“Do you think Lukamba knows he has your wife and child?” Drury asked.

Ngola pulled again. Stories were often told of the things Lukamba knew, and the bloodthirsty way he learned of those things. “Perhaps I will ask Lukamba when I see him. Perhaps I’ll just cut his throat and listen to him drown in his own blood. Why he has done what he has done will not matter because he will be dead.”

Wading through the knee-high rolling tide, Ngola helped pull the longboat up onto the beach only a few feet from the four longboats that had been left on the sand by the Portuguese and Lukamba. Captain Salazar had taken a large number of men with him.

In the pale moonlight, Ngola spotted the imprints of boots as well as the smaller footprints of women and children.

“Wait here.” Ngola held up a hand to hold his men back. Slowly, like a hunting cat, he walked across the beach, senses alert to the jungle twenty feet away.

Making himself remain patient, telling himself that the time he spent now would increase his chances of getting Kangela and Emeka back alive, Ngola studied the impressions of boots and footprints by torchlight. He noted the differences among them, thrusting sticks into the ground as he distinguished the tracks, trailing them for a ways till he was certain of his deductions.

He looked back at the sticks standing up in the sand and quickly counted them. The torch whipped in the wind and burned warmly across his cheek. “There are five or six children, four women, and twenty-seven or twenty-nine slavers.” He looked at his warriors. “We will be outnumbered, but I do not want to send for more men. That would take too long and a larger group will be harder to hide as we pursue them.”

Joao smiled coldly. “Then it would be best if we killed Lukamba and the Portuguese quickly when we find them.”

“Douse the torches.” Ngola thrust his own torch into the wet sand. The flames hissed as they drowned. Then he turned and followed the tracks into the dark expanse of the jungle, thankful the moonlight was finally bright enough to allow that.

Now that the scudding clouds had cleared, the full moon beamed down on the coast, but its attention filled Ngola with dread. Many evil things, legends often said, were possible under the light of a full moon.

3. The Risen Dead

Carrying a Baker rifle in one hand, Ngola tracked the trail of the slavers easily through the brush. The Portuguese crew followed an old game trail and their boots had scored the ground, marking their path.

Ngola moved at a near-run, eating up the distance quickly, and he knew he was gaining on his quarry. The earth turned up by the boot marks was fresher, still damp to the touch. He felt certain he was only minutes behind them now. The way led uphill and he wondered what had made Lukamba and the Portuguese certain that The Scorpion was nearby.

He also wondered why they had come at night.

Unless what they have to do can only be done in the darkness.

The thought jangled uncomfortably in Ngola’s mind and he glanced spitefully at the huge moon. Vodun magic was fierce and strong, and Lukamba was reputed to be a master of the dark arts. On Haiti, houngans, mambos, and bokors had wielded the spirits to work their magic. The houngans and mambos sought to cure and use their powers for good, but the bokors brought the loa into the world to kill their enemies. The French landowners hadn’t been able to stand against them, and even their fallen dead had risen once more as zombies to fight against them.

Ngola had seen such supernatural entities and had sometimes fought with them. The zombies were hard to kill.

Less than a half-hour later, torchlight gleamed higher up in the mountain where the Portuguese had traveled. The weak golden glow pooled against low-hanging trees that barely held the heavy darkness at bay. Faint wisps of an old man’s voice lifted in song pealed in the distance.

Ngola held up a hand to halt his warriors and studied the land. Drury stood tensely at Ngola’s side. The Irishman didn’t care for vodun magic either, and his people had their own brand of mysticism and fey spirits that wished only ill for men, so Drury knew firsthand what dark forces could do before he’d come to West Africa.

“Colin and I will go take a look to see what the Portuguese are doing,” Ngola told his crew. “The rest of you wait here.”

Without a word, his men melted into the jungle so cleanly it was like they’d folded up their shadows to carry with them.

Taking a fresh grip on the Baker rifle, Ngola started up the mountain, avoiding the game trail he’d been following and staying within the trees. Drury followed only a few steps behind, moving as sure-footed as Ngola.

Cautiously, Ngola crept along the final few feet to a ridge that overlooked the hollow filled with torchlight and chanting. He lay on his stomach, Drury only a short distance away, and surveyed the events taking place.

A hundred feet distant, Lukamba danced slowly over a barren area where no trees or grass grew. The bokor was thin, stripped down to skin over bones. He shook a feathered staff in his right hand. Strings of human teeth clacked against the wooden walking stick. A half skull from a great ape or gorilla covered the top of his head and down his face to his mouth. Long fangs framed his hollow cheeks. The yellowed bone gleamed dully in the moonlight.

The old man’s voice was surprisingly strong, but his words were unintelligible. They sounded ancient and hurtful, blunt weapons that had been designed to maim and destroy. Back in Haiti and in other parts of Africa, Ngola had seen the power such words could call up.

Despite the distance that lay between them, Ngola shuddered just a little, and the hair on his forearms lifted slightly. He watched intently, scouring the clearing for his wife and son.

The Portuguese sailors stood to one side. Light from the blazing torches they’d driven into the ground played over the slavers and glinted from their heavy brass buttons, helmets, swords, rifles, and pistol butts. They stood close together, not talking, and many of them gazed fearfully at Lukamba.

At their feet, the four women and six children crouched or lay on the ground. Ropes bound their hands behind their backs.

Kangela knelt in the back of the group. Despite her situation, she looked proud and regal, her head high and her eyes watchful. Athletic and womanly, her hair cut short and neat, dressed in a colorful blouse and skirt, the sight of her made Ngola’s heart swell.

The first time he’d seen Kangela, he’d thought she had the face of an angel, though he was not so convinced of the Christian heaven. He’d been wounded near unto death and had felt the life slipping from him, certain he would never wake from the black void. Then Kangela had been there, beautiful and tender and giving. She had nursed him back to health though the rest of her people had told her she should surrender Ngola to the jungle predators.

He had loved her at once because she’d been like no other woman he’d ever been with. She was strong and tender, compassionate, yet – under the right circumstances – without mercy. No one in her village was a better hunter, and she had taught Ngola much about moving stealthily in the jungle.

Emeka, their son, lay halfway draped across his mother’s knees. He was four years old, still small and innocent, his hair wild and his body so thin as he grew. Seeing him bound as he was hardened Ngola’s heart against those who had taken him. Emeka only wore a loincloth and he looked vulnerable among the armed men. Fear filled and widened his eyes.

Unconsciously, Ngola edged the Baker rifle forward as he shifted his gaze to Lukamba.

The bokor ended his litany in a high-pitched shriek and struck his staff against the barren ground as if demanding an answer or response.

Drury laid his hand upon Ngola’s shoulder and whispered almost inaudibly. “Wait, my friend, I beg you. We need to plan this, not simply leap into it if we are to save them.”

Restraining his homicidal impulses, but only just, Ngola nodded and drew the rifle back. He scanned the jungle, looking for other ways to close in on the Portuguese slavers. If he and his crew succeeded in driving them away from the captives, then the women and children would have a chance of surviving the encounter.

Lukamba gave a screeching command and threw his open hand down to hover only inches above the ground. He tugged again and again, as if he had hold of something. Even a hundred feet away, Ngola felt the sudden chill as the warmth was sucked from the air.

Glowing, malignant purple embers dropped from Lukamba’s palm and fell to the earth like rain. The embers winked out of existence as soon as they touched the ground.

At first, nothing seemed to come of the bokor’s effort. Then cracks tore through the earth and something pushed up, like a seed breaking free of its tomb to reach for the sun.

Only there was no sun, and the thing that shoved free of the ground had been dead for a very long time.

Cursing to himself, Ngola watched in rising horror as the dead creature clawed up from the lost grave. At first, as he sighted the misshapen head and the uneven shoulders, he believed the thing might be the corpse of a monkey or chimpanzee, then he realized that the shambling figure was that of a dead child.

“God in heaven, protect this wayward servant.” Drury’s whisper was louder than he’d intended, but his words didn’t travel far.

Besides that, the attention of the Portuguese slavers was focused on the bizarre resurrection taking place before them. Some of the slavers crossed themselves in the Catholic fashion. Many of them took steps back and peered fearfully at the surrounding jungle. Captain Salazar, surely the handsome and broad man dressed in finery and a cloak and wearing a fierce mustache and neatly trimmed beard, stood his ground but half-drew the cutlass that hung at his side.

Lukamba lifted his hand and pointed at the Portuguese captain. “Stay your hand if you would live, Captain Salazar.” The bokor’s voice was soft and dry as dust. “If the ogbanje senses that you mean it any harm, it will kill you.”

The gruesome creature lifted its shattered head and sniffed the air like a hyena. It remained half-crouched, swollen knees bent and desiccated flesh wrapped loosely around the bones. Tattered remnants of a loincloth hung from its waist.

“What is that loathsome abomination?” Salazar demanded. He didn’t draw his steel, but neither did he lift his hand from the weapon’s hilt.

Beneath the half-skull that masked the upper part of his face, Lukamba smiled genially at the dead thing, like an old grandfather would at a favorite grandchild. He moved slowly, balancing his staff in the crook of his arm and taking a knife from his waist. He drew the blade along a weathered crease in his palm. Blood wept from the small incision. Knotting his hand into a fist, he held it above the creature.

A long, barbed tongue shot from the dead thing’s mouth and caught the blood drops as they fell from the bokor’s fist. Tentatively, the thing reached up for Lukamba’s hand with its own. Lukamba allowed the thing to latch onto his fist, and there it nuzzled like a pup to a teat.

“This is an ogbanje,” Lukamba said. “It is a restless spirit. They are called ‘children who come and go’ because they are born into a family, then die at a very young age only to be reborn and die again so young. They are creatures of misfortune and bring heartbreak again and again to those to whom they become attached.”

The thing suckled noisily, paying no attention to the Portuguese.

“Once an ogbanje has been identified in a child,” Lukamba went on, “the child’s body is broken and mutilated and buried so it cannot come back only to die again.” The bokor smiled as the creature continued to feed. “Sometimes that breaking and mutilation and burial is not enough. As you can plainly see. Then, if a bokor is strong enough, he can raise them and they will be even more fearsome.”

Salazar’s eyes narrowed and his jaw firmed. “Where is the treasure you said was here?”

Lukamba shook his hand and freed it from the ogbanje’s grip. The creature dropped to its knees and sniffed the dirt for stray drops that might have fallen. It whined piteously as it searched.

“The treasure is close, Captain. Be a little more patient. I need the ogbanje to lead us there.” Lukamba held his hand close to the ground again and again, drawing up other ogbanjes from different areas within the barren clearing.

Within minutes, three more broken shells of dead children joined the first. Four small craters scarred the clearing. The ogbanjes milled around Lukamba like hounds at the bokor’s heels. Their plaintive keening formed a constant undercurrent of noise that hurt Ngola’s ears, as nerve-wracking as a steel blade grating against another. Lukamba allowed each of the new ogbanje in turn to feed from his hand for a moment before he shook it away.

“Have you heard of these cursed creatures?” Drury whispered to Ngola.

“I have heard of them, but I have never before seen them.” Ngola quelled the primitive fear that threatened to run rampant in him. He had witnessed magic before, good and bad, and had learned to both fear and hate it. Houngans and mambos had healed wounds and chased away evil spirits from the sick in Haiti, though Ngola had never seen those incorporeal entities and only assumed they truly existed.

“What will Lukamba do with them?”

“I do not know.” Ngola pushed that from his mind and concentrated on how he was going to save the prisoners. The people back at the Portuguese ship were safe enough for now, and would be safer still as soon as they sailed. But the women and children – Kangela and Emeka – below remained at risk.

Two of the ogbanje stepped away from Lukamba and shambled on their disproportionate legs toward the Portuguese. The slavers drew back fearfully, many of them raising pistols and rifles.

Salazar held up a gloved hand. He spoke in a quiet, deadly voice. “Do not fire. Do not attack them. If you do, I will kill you myself.”

The men put their weapons away and stepped back, leaving the prisoners at the mercy of the dead creatures.

The ogbanje walked among the women and children. Nearly all of them cried out fearfully, calling on their gods to save them and even beseeching the slavers for help.

Kangela remained quiet and watchful. When one of the ogbanje closed in on Emeka, Kangela headbutted it and knocked the undead thing away. The ogbanje squalled in pain and rage and set itself to attack.

A sharp command from Lukamba froze the ogbanje in its tracks. It protested shrilly, but ducked its dead eyes and returned to the bokor’s side where it clung to one of the old man’s skinny legs.

“All right, Captain Salazar, we may continue.” Lukamba gave a command in his native tongue and the four ogbanjes scuttled ahead of him, disappearing quickly into the shadows.

Helplessly, Ngola watched as the Portuguese slavers herded the prisoners up and followed the bokor.

“Get the men,” he whispered to Drury. “Follow the Portuguese.”

Drury hesitated only a moment, eyes searching Ngola’s face, then he nodded. “Where are you going?”

“To scout ahead for a place that we can set up an ambush.”

“Give me a moment to talk to Joao and I’ll go with you.”

Ngola shook his head. “One man will pass unheard and unseen. If there are two, there are more chances of being found out.”

“If you get into trouble –”

Ngola grinned mirthlessly, interrupting his friend. “If I get into trouble, you will know it. Rest assured. Now go. When I need you, the best you can do is be there to lead the men.”

“You have my word.” Drury clapped Ngola on the shoulder and melted into the darkness that clung to the mountainside.

Ngola looked over the jungle ahead, finding a jagged outcrop of rock towering above the trees to use as a landmark. Lukamba and the Portuguese headed in that direction.

Getting to his feet out of sight of the slavers, Ngola ran along the ridge of the mountain, just short of the crest. Using the skills that Kangela had taught him, he passed through the jungle without leaving branches or brush trembling to mark his passage. He was a ghost among the moon-cast shadows.

4. The Lost City

At least a thousand yards ahead of Lukamba and the Portuguese slavers, Ngola spotted the rope bridge that spanned a large canyon. The roar of the river racing below reached him before he got close enough to peer down into the swirling depths.

Hidden by trees and brush, Ngola stared down at the rushing river at least two hundred yards below the cliff’s edge. Jagged rocks pierced the white-capped water like broken fangs and spray sailed over them.

The bridge was narrow, at least a hundred feet long and only wide enough for one person to cross at a time. That would bottleneck the slavers and force them to cross one at a time. That could be useful, but once the women and children were on the bridge, they would be vulnerable.

Ngola cursed. Staging an ambush there was too problematic. If he and his men crowded the Portuguese, the prisoners could be used as hostages, perhaps dangled over the long drop to the river if things went badly. And there was no time to get around the slavers and return with his men to set up the ambush.

Glancing behind him, Ngola spotted the pale torchlight crowding out the night as the party of slavers approached the bridge. He felt certain they would cross the bridge. There was nothing else that would attract them on this side of the ravine.

Across the bridge, though, the mountain towered another thousand feet or so, spiking toward the dark sky, narrowing to a point like a spear. Trees and shrubs clung to the mountain’s exterior. Nothing there gave any indication why Lukamba trekked in that direction. However, the river below was wide enough to have permitted a sailing vessel at some point.

Perhaps the myths about The Scorpion were true. If Ngola’s family had not been presently at risk, he might have enjoyed thinking about the possibility of riches awaiting the night’s efforts. Tonight, though, he planned only bloody revenge.

Deciding he wanted to know more what lay on the other side of the river than to wait on his men and cross later, Ngola sprinted for the bridge with the Baker tight in his fist. Reaching the massive pole driven into the ground at the cliff’s edge, he turned without hesitation, but with considerable trepidation, and trotted across the bridge.

The wooden slats clacked and shifted beneath his boots, but they held his weight easily, surprising him greatly. It looked like no one had come this way in years. Moss and small plants had taken root in the braided rope cables and some of the wooden slats.

He reached the other side without being seen, glanced around till he found a game trail off to his left, then followed that for a moment. Inside the brush, the game trail crossed an old stone avenue obscured by the forest.

The jungle had overgrown the stone pathway to a large degree, but there was no doubt that the way had been cut through the brush and trees at one point. And there was no doubt that no one had come this way in years, perhaps generations. The road was eight feet wide and laid with four-foot squares of thick white rock slabs that had been quarried and placed with care.

Stepping onto the nearest stone, Ngola slammed his foot against the surface and found it hard and firm. Grass and roots disturbed the lay of some of the stones, shifting them up at angles and partially covering them, but the direction could be easily discerned.

Ngola stayed off of the pathway, choosing instead to move quickly beside it. Walking on the stones would have left fresh tracks and he didn’t want to risk that someone among Salazar’s crew might be sharp enough to catch those marks and know them for what they were.

Glancing back the way he’d come, Ngola spotted the Portuguese sailors crossing the bridge in single file. As Kangela and Emeka walked the bridge as it swung, he tried not to think of the long fall that lay below them if the supports gave way. His wife kept one hand on their boy’s shoulder, gently guiding him, and he walked with his head high.

The ogbanje cavorted around Lukamba, unmindful of the long plunge to the river. They spun and twirled along the ropes, like they were gamboling on a walk.

Ngola said a silent prayer for his wife and son, then focused on seeking out the eventual destination. He started forward again, then paused long enough to make sure the Portuguese and the bokor traveled in the direction he’d chosen.

They made the turn and came after him. Their torchlights seared the shadows from the tree canopy as they traveled.

Ngola pressed on.

The white stone pathway came to an end at stone steps that led up into the mountains. A long time ago, walls had stood on either side of the steps. Their crumbled remains lay amid the jungle, almost swallowed up by trees and brush. Occasional moonlight glinted off surfaces, making the straight lines stand out against the riotous form of the jungle.

At the foot of the steps, Ngola gazed up and discerned that the ruins of a small town lay before him. He sifted through the myths and legends he’d heard of lost cities in this part of West Africa, trying to identify which this might have been. There were so many stories, though, so many lost places. Every tribe had its folklore about forgotten civilizations that had fallen through the cracks of time, and all of them might possibly contain a kernel of truth.

So much of Africa’s past had been wiped out. Lives had winked out like sparks rising from a cook fire, and histories had gotten lost and scattered. Ngola believed that Africa would remain forever splintered, never again to be made whole, never to be made strong against invaders that preyed upon her shores and took whatever they wished.

He shook those bleak thoughts from his mind and focused on saving his wife and son, and keeping his crew as safe as possible. They would shed more blood tonight, he knew that was unavoidable, but he did not want to lose any more of his people if it could be helped.

With the Baker rifle at the ready and the bokor and his inhuman companions at his heels, Ngola entered the forgotten city. Trees and brush grew along the roads that lay half-buried in dirt and grass. Night birds and bats flickered between the branches and through the arches that remained of doorways. Hyenas cackled in the distance. Almost all of the original houses had fallen over the passage of time, but here and there small buildings yet remained.

The town had been built around a natural cistern that formed a deep bowl in the harsh, rocky landscape at the foot of the mountains. Rains had come down the mountain face and pooled in the bowl. A manmade trench three feet wide led back to the chasm where the bridge was. Ngola guessed that the trench had been constructed to keep the cistern from overflowing during the rainy season.

Skeletons of people, donkeys, and other animals lay around the water’s edge, enough so that Ngola wondered if the water had been at one time poisoned.

Closer inspection revealed that nearly all of the human skeletons were of full grown men. Many of them had weapons – spears and stone axes and crude swords forged of hammered bronze – close enough to hand that Ngola believed they had died fighting.

Several of the skulls lay cracked and shattered. Smashed ribcages revealed more signs of violence. Some of the newer skeletons, though those were old as well, wore Portuguese breastplates and had more modern weapons, though those too were dated.

Ngola’s grip on the Baker tightened as he surveyed the battlefield. Whatever had killed the original inhabitants had risen up and killed again. Fear thrummed through him, a buzzing, insistent force. Every instinct in him clamored for him to quit the place as quickly as he could.

But he would not leave Kangela or Emeka. When he left, he would take them with him. And they would be avenged.

Forcing himself to stand his ground, taking a firmer grip on the Baker and tracing the hilt of one of his cutlasses, Ngola surveyed the cistern’s dark water. The bowl was at least seventy yards across. In times past, the water level had been higher. Water stains on the alabaster rock revealed the old capacity. The present level was nearly three feet lower than the highest stain.

Moonlight shimmered across the surface stirred by the whispering wind. The water looked oily and black, and though Ngola would have liked to slake his thirst, he dared not. Nor did he get too close to the water’s edge. A cold, instinctive warning trickled through him and he took two steps back before he realized he was moving.

Light flared at the corner of his eye, and he turned toward it, raising the Baker rifle.

Torches burned brightly in the hands of the Portuguese sailors as they tramped toward the ruins. Their gear jingled as they walked, and their whispers sounded tight and frightened.

Ngola melted back into the shadows a short distance from the cistern, staying to the right midway between the front of the cistern and where it butted up against the mountain. Standing behind a stone arch that listed to one side, he made the Baker ready and breathed quietly.

Lukamba walked without hesitation to the cistern’s edge. The ogbanje paced stolidly at his side, no longer capering like demented children. They were focused and attentive. Their empty eye sockets remained riveted on the dark water.

The Portuguese halted several feet distant and huddled together under the fragile umbrella of light from their combined torches. Fear etched their faces, and Ngola knew they too felt the evil that lurked in the tumbled-down city.

“Lukamba.” Hand on his cutlass, Captain Salazar strode toward the bokor. “What is this place and why have you brought us here? Where is the treasure?”

Setting his staff on the ground, Lukamba answered the Portuguese captain but kept his attention riveted on the cistern. He stretched forth his empty hand over the dark water. A purple glow emanated from his palm and fingers and the glow reflected on the surface.

“Patience, Captain. Your treasure is at hand.” Lukamba closed his eyes as if in prayer. “This place is Abiku, the city of death. Long and long, it has lain here, a corpse of broken rock and shattered power, but within its bones it has held many things of great power.”

Salazar kicked at a pile of bones in disgust. “It’s a city of corpses, I will grant you that, but I do not see The Scorpion or the treasure.”

“Abiku holds old secrets here, Captain. Powerful secrets. The Scorpion came here, but the ship did not leave.”

“Then where is it?”

“Hidden. As many things here are hidden.” Lukamba closed his hand and made a fist. The purple glow grew stronger, throwing a cast of light over his withered mouth and the half-skull that he wore. He smiled, and the expression held nothing good in it. “We are here tonight to uncover these things.”

New ripples shifted across the cistern.

At the front of the line of hostages, Emeka grew more frightened. He clung to Kangela’s hand and stepped back to take shelter behind his mother. Behind the arch, Ngola leveled the Baker rifle and held the sights steady on Lukamba. One of the ogbanje slowly turned around and scented the air, then directed its gaze at Ngola’s hiding spot.

Ngola cursed quietly, knowing then that the foul little thing was somehow sniffing out his intent. Reluctantly, Ngola shifted his aim and stopped breathing, willing his heart to beat more quietly.

The ogbanje shifted a little uncertainly, then uttered a plaintive cry.

Lukamba ignored the dead thing and concentrated on his task. Silently, the other three ogbanje turned in Ngola’s direction as well, staring at him across the expanse of dark water.

“Abiku is an important place, Captain. A place of power for the man who knows how to wield such power.” Lukamba’s voice softened yet sounded more powerful as it carried across the cistern.

Ngola knew the change in pitch was affected by the hollow shape of the cistern and the fact that water carried sound better than the land. He watched the ogbanje, praying they did not seek him out in that moment.

Shadows flickered behind the Portuguese and Ngola’s keen eyes made out the gleam of moonlight on metal. Relief took the edge off the fear that gripped him when he realized Drury and the rest of his away party had joined him there in the ruins. They were still outnumbered, but they had surprise on their side.

For the moment.

“If you were lying to me, old man, I will see you drawn and quartered ere the dawn lights the eastern horizon.” Salazar took another step forward.

Instantly, the four ogbanje wheeled on the Portuguese captain, no longer searching for Ngola. Salazar drew one of his pistols in a blue of speed that impressed Ngola. Legends insisted on the captain’s speed and deadliness. The heavy pistol barrel centered on the back of Lukamba’s head.

“Call off your pets, sorcerer.” Salazar spoke in Portuguese. “Or I will put a bullet through your brain.”

“If you should decide to do that, the ogbanje would kill you and feast on your blood.” Lukamba continued speaking softly, as if he had no concerns in the matter. “I ask only that you bide your time a moment more. Then all will be revealed.”

Salazar held his aim a moment longer, then raised his pistol to point at the heavens. “A moment more is all.”

Lukamba gestured to the ogbanje and spoke in a language Ngola did not understand. They were guttural words, hard and ringing.

Instantly, the ogbanje walked to the water’s edge and placed their misshapen hands on the stone. When they lifted them back up, they held tall, conical drums. The ogbanje stood the drums before them, then began hammering the tautly stretched skin that covered the instruments.

Taking his spyglass from his pouch, Ngola examined the drums. They’d been constructed of bones woven tightly together. The stretched skins still bore some of the features of men and women that had been sewn together to create the cover. The vibrating skins made it look like the faces were crying out in pain.

The hollow thumping of the drums started off slow but quickly gained speed, filling the dead city with menacing noise.

“What are you doing?” Salazar took a step back in spite of his bravado.

Behind their leader, the Portuguese men huddled more tightly together. Kangela shifted Emeka behind her, placing herself between their son and the bokor and the dark cistern.

“I am calling forth that which will not die.” Lukamba’s voice rose above the thumping of the drums. His closed fist glowed more brightly. “Long and long have I searched for the secret to this place. I did not guess that your search and mine would fall so closely together, but it was meant to be. Perhaps you follow dark gods as well.”

“I do not follow heathen gods,” Salazar growled.

“You do not follow your chosen god either.”

“Do not mock me.”

The drums grew louder and louder. Ngola felt the hollow beats burn and leap through his blood. The music reached back into a forgotten part of himself, igniting those memories of Africa and the boy he had been before the slavers had captured him and sold him off to the plantation owners in Haiti. He wanted to weep for all that he had lost, but the fear that slid greasily through him erased all gentle thoughts from his mind.

“The original inhabitants did not know of the god that sleeps at the bottom of this cistern.” Lukamba raised his gnarled fist above his head. “They knew only that this was an easy place to live. Sheltered from their enemies, they built their homes and raised their crops and tended their cattle. They did not know they had trespassed. Not at first..”

The whirling tempo of the drums sped up more as the ogbanje beat madly at them. There was not just one beat now. The demonic dead things had woven in two beats that sometimes complemented the original and sometimes fought to be unleashed.

“One day, though, the god awakened and demanded his tribute.” Lukamba shivered as though chilled. “Abiku rose up from the water and killed them, leaving only a few to tend his needs. They served him, giving him their children, feeding his dark hunger when he called out to them.”

“Why did those people not simply leave?” Salazar asked.

“Because Abiku bound them to him. The people found that when they left this place, they sickened and died. No one could escape. They lived only to be his sacrifices, his amusements and his pleasures and his prey. And their children served in their time. Until they rose up against Abiku and he struck them down.”

“Better to die a free man than live in thrall to a demon.”

The irony of Salazar’s declaration was not lost on Ngola. In many places, the Portuguese slaver himself was cursed as a demonic entity.

“Given the choice, Captain, what would you do?”

“Me?” Salazar forced a laugh, making it loud enough to pierce the drumming. “I would put a ball through your head and end this farce once and for all.”

“Would you?” Lukamba smiled, then turned to face the slaver captain. “We will see.” The old bokor threw his arms skyward, seized his staff in both hands, and barked more guttural words as the ogbanje ceased their mad drumming. Something shimmered in the air above the spear, then dove into the water.

The last notes of the drums drifted away, lost in the ruins of the city.

For a moment, fragile silence stretched over the cistern.

Then Salazar laughed. “Perhaps your dark god is not yet ready to rouse from his nap, old man. Or maybe these people killed him and left him to rot in his little pool.” He leveled the pistol again. “Now I will have my gold or I will throw your corpse to the fishes and eels that might live in those fetid waters.”

The cistern’s calm surface erupted in a wave of spray as the monstrous thing that lay beneath lunged up.

5. Dark God

The serpentine shape towered twenty feet above the cistern. A monstrous wedge-shaped head split open to reveal fangs as long as a man’s arm, and a forked, black tongue flicked out to taste the air. Two sets of huge ebony eyes were set one above the other, the higher ones spreading out farther to the sides of its face. Great fins flared out on either sides of the thing’s head. The moonlight dappled the creature’s scales in shimmering blues, greens, and purples. Its belly was lighter in color than its dorsal side.

Captain Salazar swore and shifted his pistol from Lukamba to the behemoth writhing sinuously behind the bokor. The muzzle flash burnt a hole in the darkness and gray powder fogged out, then the crack! reached Ngola’s ears.

Abiku loosed an ululating wail, but Ngola knew that the sound was not caused by whatever small wound the Portuguese captain’s pistol might have made. The demon-thing was much too massive for a lone pistol ball to have done much damage.

“Kill that thing!” Salazar dropped his first pistol and drew another, stubbornly standing his ground.

Trained to obey their leader in battle, the Portuguese slavers drew forth their weapons and opened fire. The pistol shots sounded brittle and gunsmoke lay thick over the sailors.

“Reload!” Salazar commanded as he drew another of his pistols.

Obeying at once, the Portuguese set their rifles on the ground and reached for powder and shot. They worked mechanically, by instinct, for their fearful gazes were locked on the monster that swayed above them.

The ogbanje beat on their drums again, as quick and threatening as ever.

The thing spoke in a sonorous language. The sounds were too methodical to be incoherent growling. Lukamba turned back to the creature with his staff held high and spoke in the same language. He abased himself in front of it, dropping to his knees, and pointed not at the Portuguese as Ngola had expected, but at the women and children left huddled in front of the slavers.

Abiku roared and the sound rolled up the mountainside. Quicker than the thing had any right to move, it darted forward and seized two women and a child in its gaping maw. Teeth gnashed together, slicing its victims into pieces, and red blood poured down its chin.

Kangela seized Emeka’s hand and propelled the boy backward as the Portuguese sailors fired again. The balls struck the creature, but most of them deflected from the scales and the others only made small wounds that barely trickled green blood.

Ngola raised his rifle and targeted Lukamba. When the sights settled over the bokor’s withered mouth, Ngola squeezed the trigger. The rifle jarred his shoulder. At the same moment, Lukamba ducked his head to the fearsome creature gulping its grisly meal before him. The ball struck the skull mask Lukamba wore.

Knocked backward by the ball, Lukamba rolled awkwardly. For a moment Ngola thought he had killed the bokor, but even as Ngola poured more powder down the throat of his weapon, Lukamba stirred and raised himself on hands and knees. The shattered skull mask fell from his face. He shouted at the monstrous thing and the ogbanje beat the drums furiously.

“Reload!” Salazar yelled as he squeezed his pistol’s trigger. The crack! pierced the drumming but for a second. Instead of aiming at the creature, Salazar had aimed at Lukamba.

The old bokor lifted his staff and screamed in his foreign tongue. Purple sparks flashed a foot in front of his face and the pistol ball stopped in mid-flight, then dropped to the rocky ground.

Still chomping on his helpless prey, Abiku swept toward the Portuguese. Most of them had started reloading their weapons, but all of them abandoned the long guns and reached for their blades as the monster came for them.

Kangela reached the Portuguese and tried to break through. A swift kick sent one of the men to the ground. Kangela stole the fallen man’s knife from his belt and buried it in the throat of another man who reached for Emeka. As the dying man stumbled backwards, the man behind him shoved him aside and leveled his pistol at Kangela.

Shifting his aim from the bokor, Ngola aimed at the Portuguese sailor’s face and pulled the trigger. The ball slammed the man’s head backward, then he dropped to his knees and fell forward on his face.

Abiku struck the midst of the Portuguese, scattering them at first, then plucking up five of them with long tentacles that suddenly uncoiled from its neck. The screaming men hung like fruit from the monster’s appendages, and it ate one of them like taking a grape from a bunch.

“Drury!” Ngola shouted. “Get Kangela and Emeka out of here!”

Lukamba whirled around to face Ngola. Rifle ready again, Ngola took aim at the bokor and fired as the old man lifted his staff and shouted again.

The ball stopped in mid-air amid a shower of purple sparks, then dropped.

Lukamba laughed and preened. “Captain Ngola. I missed you at your village, but I have you now. This is an unexpected pleasure. And your wife and child are here too.” He shook his head. “There will be no escape from this place.”

Ngola tossed the Baker rifle aside, knowing it would be of no further use. The balls couldn’t reach Lukamba and they were ineffective against the creature.

Some of the Portuguese broke and ran, racing back along the way they had come only to be met by Drury and the away party. Drury, Joao, and some of the other men fired their weapons, cutting down the slavers before they reached them. The bodies of the Portuguese toppled to the ground as one of the fleeing women and two of the children raced past.

Abiku loosed another ululating wail that reverberated from the mountain and echoed over the countryside. The air just beyond Drury and the men wavered and Ngola felt the hum of electricity.

The woman and the two children never slowed down, but when they reached the wavering area, eldritch magic stripped the flesh from their bones and they fell to the earth as gleaming ivory skeletons and the demonic drumming from the ogbanje continued around them. Two other children had been at the woman’s heels.

Drury caught one of the children and halted her, but the other was past him before he could grab her. She met the same fate as the others, falling to the earth beside them.

Barely controlling the horror that filled him, Ngola stared at the heaps of bones.

Lukamba cackled gleefully. “I told you that none of you may leave this place. You can serve Abiku, or you can die.”

Either way, Ngola knew, death was in the cards – if they couldn’t find some way to break free of the creature’s power. Ripping his cutlasses free of their sheaths as he ran down the incline to the cistern, Ngola thought back to the houngans and mambos he had met while on Haiti and along the West Coast. Vodun was powerful, but it had its weaknesses. Blood, fire, and salt all disrupted spells, curses, hexes, and the evil eye. Even non-practitioners had defenses against the unwanted attentions of the loa.

The hapless Portuguese in the monster’s tentacles cried out for help, but their pleas fell on deaf ears. Captain Salazar tried to marshal his men to him, but that task was made harder because Drury and the away team pressed them hard, shooting them and keeping them penned between them and Abiku.

“Father!” Emeka stood within his mother’s sheltering arms and stared at Ngola.

“Husband!” Kangela held her position, but Ngola knew she was torn between her son and fear for him.

“Stay, Kangela! Keep Emeka safe!” Ngola sprinted toward Lukamba.

The old bokor raised his staff in defiance and threw out his empty hand. Purple flames lashed out like a whip, narrowly missing Ngola as he slid beneath them. Once the flames passed overhead, Ngola popped back to his feet, still clutching the cutlasses in his fists.

Abiku lashed out at him, dropping its massive head earthward. Ngola leapt, throwing himself high into the air and reversing the cutlass in his left hand. As his boots claimed brief purchase on the monstrous head, he shoved the cutlass deep into the scaly flesh.

Roaring with rage and pain, Abiku lifted its head. Three whiplike tentacles streaked toward Ngola. Swinging his remaining cutlass, Ngola hacked the tentacles off close to the thing’s body. Green blood jetted from the stumps. Other tentacles slammed a Portuguese captive into the monster’s body close to Ngola.

Holding fast to the embedded cutlass, Ngola reversed his second cutlass and slammed it home into the monster’s flesh as well, then yanked free the first. He pulled himself farther up on the thing’s head, cutting two more tentacles away as though clearing brush.

Abiku roared again and its pain and anger seemed to shake the mountainside. Writhing, it shifted again, trying desperately to unseat Ngola. Clinging fiercely to the embedded cutlass, Ngola planted his free blade in one of his opponent’s eyes. Bellowing mightily, Abiku crashed its head into the ground.

The impact jarred Ngola loose. Knowing he could no longer manage a hold, Ngola kicked free, angling his fall toward Lukamba. The bokor stood frozen, watching in disbelief as Ngola launched himself. At the last moment, Lukamba realized where Ngola was headed and tried to flee, but it was too late.

Ngola landed boots first on the old man and drove him to the ground. Lukamba’s spine snapped like a twig. He lay on his face, huffing and trying to breathe the dirt.

Rolling to the side, Ngola came up with his cutlasses in both fists. His dark gaze raked the monster as it bellowed and wallowed in the cistern. Two Portuguese sailors still lay within its tentacles like bizarre ornaments. They squalled in fear, wide-eyed and crazed.

“Ngola!” Kangela yelled.

Ignoring her, Ngola focused on saving them. Blood, salt, and fire – those were the things used to banish vodun. He hoped that would be enough.

A ragged breath tore through Lukamba’s broken mouth. Reversing the cutlass in his left hand again, Ngola slammed the blade through the bokor’s back and into the earth. Then, as the monster twisted its gargantuan head to see him again – only one eye on this side now, Ngola knelt to search through the old man’s pack. One of the first things Ngola found was the salt sack the bokor kept to create protective circles around himself when he dealt with the dead things.

Ngola claimed the salt as his own and dodged away as Abiku lunged at him. After taking the salt sack in his teeth, Ngola drew one of his pistols and shoved it toward the monstrous thing’s remaining eye, then pulled the trigger.

Green ichor sprayed from the ruined orb as a small cavity opened up. Two tentacles snaked along the ground and wrapped Ngola’s right ankle. Howling with murderous intent, Abiku lifted its head.

Desperately, Ngola flung the spent pistol away and seized the bokor’s staff from nearby. His fingers just grazed over the hardened wood at first, but he got the staff on the second try. He curled the staff into his fist and watched in horror as the thing dangled him over that monstrous maw.

Ngola maneuvered the staff, hoping that the fire-hardened wood and whatever magic it held made it stout enough. The needle-sharp teeth closed around him, then stopped when the staff prevented the massive jaws from closing.

Holding onto the staff to provide leverage, Ngola twisted and thrust the cutlass into the thing’s snout, hoping it was sensitive. Undoubtedly the snout was sensitive enough, because Abiku screamed and sent two tentacles slithering for the weapon.

Taking advantage of his momentary respite, Ngola grabbed one of the teeth with his other hand and hauled himself into the creature’s mouth. Bracing his back against the roof of the monster’s mouth, legs trembling with exertion to keep him locked in place, Ngola opened the salt sack and spilled the contents down the thing’s throat.

Abiku’s cries came to an abrupt halt as it choked.

Pulling the powder horn from his side, Ngola pried it open and scattered the gunpowder down the thing’s throat as well. Taking the mambele from its holster at his back, Ngola sliced a long furrow along his arm. His blood mixed with the salt and gunpowder.

“With my blood, I curse you to hell, to rot and to die, in agony and fire.” Ngola pulled his flint from his pouch and struck sparks from it with the mambele.

Flames leapt up as soon as the sparks touched the gunpowder. Some of the powder was wet from the creature’s saliva, but enough remained to guarantee a hearty blaze.

Ngola reached up and grabbed the staff as the monster shook its head in a dizzying whirl. Several tentacles snaked into its mouth, rushing over Ngola but not closing on him. He forced himself between the thing’s jaws, escaping just before the tentacles pried the staff loose. He landed on the monster’s chin as the massive teeth slammed shut.

Smoke blew out the monster’s nostrils and gills, and fire lit it up from inside. The head snapped and jerked in agony.

Heaving himself away from the creature, Ngola tumbled to the hard ground and came up on his feet immediately. He lunged to the side, shoved a foot down on Lukamba’s corpse, and pulled free his cutlass. He turned to face the cistern again, expecting the monster to come for him.

Instead, Abiku dove into the black water.

For the first time, Ngola realized that the drumming had stopped. He gazed along the shore and saw the four ogbanje lay sprawled in death again. As he stared at them, the corpses withered and turned to ash. Whatever dark magic had animated them had gone. The drums aged and collapsed, falling into pieces as the leathery faces curled up and tattered.

A moment later Abiku’s corpse floated to the top of the cistern. The two remaining eyes were glazed over in death.

Remembering there was still a fight to be fought with the Portuguese, Ngola turned around and took a fresh grip on his cutlass and drew one of his remaining pistols.

Captain Salazar lay dead on the ground. His men lay dead around him. None had been spared. Mercy wasn’t something Ngola’s crew was prepared to give to slavers.

In the next instant, Emeka ran to Ngola. Smiling, Ngola dropped to one knee and wrapped an arm around the boy, lifting him easily as he once more stood.

Tears streaked Emeka’s face. “I thought the monster had eaten you.”

“No. I crawled inside him and killed him.” Ngola grinned. “I only did it to worry your mother.”

“She was scared.”

“Then it worked.” Ngola strode forward and slipped his cutlass into its sheath, then took Kangela under his arm as she came up to embrace him. He leaned down and kissed her, feeling all the warmth and love that a man could ever feel, and those were the things that made the battles a man had to fight worthwhile.

Drury joined them, bloodied and worn.

“How many did we lose, Colin?”

The Irishman grinned and shook his head. “Not a one. The Portuguese were too worried about that thing to pay much attention to us. By the time they decided to attend to us, it was too late.”

“Good. Do we have wounded?”

“Not so wounded that we can’t leave.”

“Then let’s leave.”

Drury grinned again. “Mayhap you’ll want to tarry a little longer, Captain.”

Ngola studied his second-in-command silently for a moment. “I have memories enough of this place.”

“Aye, and I do as well. However, I wouldn’t want to go off and leave all that gold.”

Ngola thought about that. “You found The Scorpion?”

“Near enough.” Drury jerked a thumb over his shoulder. “While we were scouting the city, Joao discovered one of the collapsed houses covered a tunnel leading down to a cavern at the river’s edge. The Scorpion’s inside. She’s still got her cargo aboard. From what Joao says, it’s going to take us a few days to load it all up.” He grinned again. “I’m thinking there’s enough to give your wife’s people a fresh start somewhere else and allow us to take some downtime. God knows we’ve earned it.”

Ngola nodded. “We have, and Kangela’s people will need to be relocated. We cannot take any chances that Salazar might have gotten word to the Portuguese that he had found them.”

“Want to come down and take a look?”