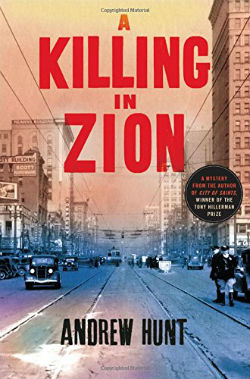

A Killing in Zion by Andrew Hunt is a historical murder mystery set in Salt Lake City featuring Detective Lieutenant Art Oveson (available September 8, 2015).

A Killing in Zion by Andrew Hunt is a historical murder mystery set in Salt Lake City featuring Detective Lieutenant Art Oveson (available September 8, 2015).

In the scorching, drought-plagued summer of 1934, as wildfires burn across Utah, Detective Lieutenant Art Oveson faces a unique assignment. Salt Lake City's mayor has tapped him to revive the Anti-Polygamy Squad, a unit formed years earlier for the purpose of driving out the city's “plural marriage zealots.” As a Mormon ashamed of his own ancestors' part in the church's polygamist past, Art is eager to do his part to flush out the extremists.

Then a local polygamist “prophet” is brutally murdered and a shell-shocked young girl is found at the scene of the crime. Is she the victim's daughter, a child bride, or the murderer herself? Art attempts to investigate the death, as well as discover her identity, despite a “wall of silence” put up by polygamists who would rather mete out their own rough justice. Soon, however, Art discovers that the sect has much more to hide than he thought.

One

Saturday, June 30, 1934

“Crime does not pay!”

The deep voice belonged to a slick gent in a tuxedo, who seconds earlier had slunk up to a radio microphone on a stand. A blinking light above the stage cued musicians in a cramped orchestra pit. The house lights dimmed as the music swelled. The theme song relied heavily on violins, with a few horns sprinkled in for sinister effect. The packed studio audience included my wife, Clara, and my two children, Sarah Jane, age eleven, and Hyrum, five. Earlier in the afternoon, the show’s producer had asked me to sit on a stool by the stage so I could get a choice view of the actors. The show, he informed me, was being “transcribed” (a word radio big shots used for “recorded”) for nighttime broadcast coast to coast on the NBC radio network. He asked if I’d be willing to answer a couple of questions at the microphone at the close of the broadcast. I said I’d be happy to do it, but stage fright ate away at my stomach something fierce, and I don’t think I ever stopped squirming on that hard wooden surface under my behind.

A technician in a glass booth pointed at the widow’s-peaked announcer, who responded with a nod and read from a script in his hands. When he spoke, his voice came out more resonant than I expected, especially for such a lean man.

“Welcome to Crime Does Not Pay, a copyrighted program, transcribed in Hollywood, USA, presented to you by Bromo-Seltzer, for quick, pleasant relief of upset stomach, nervous tension, and headaches.”

I could use some of that, I thought.

Music thundered in the background as he continued: “Each week, Crime Does Not Pay brings you a dramatic reenactment of real-life police cases from across America. Tonight, we are proud to present, from the files of the Salt Lake City Police Department, the Case of the Running Board Bandit.”

The actor playing me, Lyle Talbot, walked out from behind the curtains and the flashing APPLAUSE light nudged the audience into action. The handsome Talbot bore no resemblance to me—no hint of my gangly frame, ruddy complexion, or unruly auburn hair—but I suppose it didn’t matter, this being radio and all. Debonair, in a three-piece suit, with slick dark hair, Talbot held a script and mouthed “thank you” repeatedly. As the applause and music quieted, he closed in on that silvery microphone and read the lines without even glancing at his script.

“My name is Patrolman Arthur Oveson,” he said. I bowed my head, containing my embarrassment with a shaky inhale. “I’ve walked the night beat in Salt Lake City for the past four years. My job: to keep the good men and women of this town safe. I have a beautiful wife and the finest children a father could ever hope for. I can honestly say the last place I ever expected to find myself was on the bad end of that .38 Special wielded by the notorious Running Board Bandit.…”

The music flared up again as more cast members poured out from between the curtains and gathered around the microphone.

“Beware of the Running Board Bandit, gentlemen,” said the actor portraying Sergeant Noel Gunderson at roll call. “He operates at night, and his method is to crouch low on the passenger side running board of automobiles with his pistol and wait for the unsuspecting driver to get in. When that happens, he pops up like a jack-in-the-box, demanding money. The bandit is armed and dangerous. If you encounter him, exercise utmost caution. That is all.”

The actor playing my partner, Roscoe Lund, seemed mousy, with too much pomade in his hair. He bore no resemblance to the genuine Roscoe, whose shaved head, muscular physique, and thick neck frightened off even the most stalwart of lawbreakers. The actor playing him made up for his slight and shifty-eyed appearance by acting the part with a gravelly voice. I had wondered how the scriptwriter, who consulted me months ago by telephone about the particulars of the case, was going to portray Roscoe, a profanity-spewing cop who’d recently given up cigarettes in favor of chewing tobacco and always kept a flask full of some kind of booze in his pocket.

I soon found out.

“Heck, Art, do you really think it’s a good idea to put yourself in danger by going out there alone at night with all of them dang robberies happening?” asked the ersatz Roscoe. “You’re gonna get yourself hurt or even killed if you insist on being so gol-durn pigheaded!”

Heck. Dang. Gol-durn. A trio of words I’d never heard Roscoe utter. His tastes were decidedly saltier when it came to expletives.

I chuckled softly as I listened to the performers read one melodramatic line after another, talking in a way we’ve never talked before. I must confess: The part of the show that really gave me the jitters was the exchange between the radio Art and the radio Clara. During it, I swiveled on my stool to glimpse Clara’s radiant face and beautiful golden hair, styled in a permanent wave. She must’ve seen me, because she flashed a pearly smile in my direction before shifting her gaze back to the actors on stage.

“Oh, Arthur, please do be careful, darling,” said the pretty, petite, and crimson-lipped actress playing Clara. “The thought of you being robbed by this treacherous criminal is more than I can bear. Remember, we have children, and I do not wish to be a widow!”

“I have to do my duty, dear,” said Talbot. “You knew when you married me that you would be the wife of a policeman. Danger, I am afraid, goes hand in hand with the job.”

“Oh, Arthur, kiss me!”

The radio Art and radio Clara refrained from kissing as the orchestra played. I think I spotted Clara winking at me in the darkness. In that instant, much to my relief, the Bromo-Seltzer advertisement interrupted the action.

I loosened my collar when it came time for the radio Art to confront the Running Board Bandit. Memories of that frightening encounter, on a crisp, chill fall night last year, came flooding back to me. The shock of a pistol’s cold steel against my neck, the startling click of its hammer, so much louder when it is aimed at you—it all made my heart race, then and now.

Until that night, I’d only heard stories from others about Henry Grenache, the twenty-two-year-old unemployed miner whose purchase of a .38 caliber six-round revolver from a downtown pawnshop last summer set off a chain of late-night robberies around the Salt Lake Valley. The Running Board Bandit quickly became something of a local legend, a spooky story told around dinner tables and campfires. Such tales prompted even the most stout-hearted to check over their shoulders at night and made nervous teenagers rush home before curfew. When my brush with him finally came, it frightened me to the core, bringing me in touch with my own mortality in a way that few events up to that point had. How was I to know that night when I dashed inside the Brigham Street Pharmacy on South Temple and E Street to buy a bottle of milk and a Bit-O-Honey that he’d leap out of the bushes and crouch on the running board of my Oldsmobile with a loaded gun, awaiting my return?

I didn’t see his face when I got back in my car, only his silhouette and the glimmer of the weapon aimed at me from the other side of the glass. His voice was muffled. “Raise your hands where I can see ’em!” I did as he demanded and he opened the rear passenger-side door, slithered inside, and pressed the gun to the back of my neck. “One wrong move and I’ll blow your brains out. Gimme your wallet. Now. Now!” Shaking, feeling cold steel next to my earlobe, I fumbled for my wallet and passed it to him over the seat. The crack of a heavy gun butt against the back of my head sent my face slamming against the steering wheel. I wasn’t sure what hurt worse, the back of my head or the new cut on my lip. I was too frightened to make a fair assessment. But leaning over the steering wheel, I spied the tire iron poking out from under the seat. Grenache’s voice told me he was distracted. “See what you’ve got in here … Oh Christ, you’re a…” I grabbed the long metal tool and swung it at him, connecting with his head. He screamed, toppled backward, and fired his gun. The bullet ripped through the car roof, and a ray of harvest moonlight poured in. A second later, I was aiming my sidearm at him as he rubbed the cut on his head. I switched on the interior globe to get a better look at him. The left side of his face was covered with blood, and greasy strands of hair dangled from the top of his head as he slumped back against the seat, moaning in terrible pain.

The actors at the microphone brought me back to the here and now.

“I can’t believe you knocked me in the head with a jack handle, copper!”

“You should know by now, Grenache, that crime does not pay.…”

That set off the orchestra. Climactic music filled the radio studio as the two actors stepped away from the microphone. “And now, a final word from the real Arthur Oveson,” said the announcer. “Detective Oveson, would you kindly join us?”

The audience clapped as I rose from the stool and crossed the stage. I shook hands with the announcer and all of the actors during the applause.

“You did a splendid job playing me,” I told Lyle Talbot.

He smiled with his mouth and his eyes and whispered his thanks.

“Detective Oveson, please step to the microphone,” said the announcer. I nodded and moved in close. “I believe I speak for all of our listeners across America when I say that your heroism on that night back in November was truly inspiring.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“I understand you were given a promotion after this harrowing incident, Detective Oveson.”

“Please call me Art,” I said. “And yes, I was promoted to the detective bureau. I now command my own squad in the Salt Lake City Police Department.”

Scattered applause crackled.

“I see! Congratulations!”

“Thank you.”

“Do you have any parting words, especially for the boys and girls listening to our show tonight?”

I nodded. “Yes, I do. Stay in school, study hard, do your homework. And if you ever find yourself in trouble, tell a grown-up, especially if that grown-up happens to be a police officer. We’re here to help you in any way we can.”

“Thank you, Detective Oveson, for those wise words. And that concludes tonight’s episode of Crime Does Not Pay, brought to you by Bromo-Seltzer.” Dramatic music filled the studio again. “Be sure to tune in next week at this time as we present the intriguing case of Cleveland’s Phantom Burglar. For the National Broadcasting Company, this is Red Wilcox bidding you good night from Hollywood, USA.”

* * *

I white-knuckle-gripped the armrests as the airplane bounced in midair. Between bouts of turbulence, I checked over my shoulder to see Clara and Hyrum in the row behind me, both sound asleep. Now eight months into her pregnancy, Clara’s stomach formed a glorious dome under her green frock. Hyrum sucked his finger while he slept, a habit that had persisted since infancy. I caught my breath and faced forward. Our plane, a dual-engine United Airlines with a pair of roaring propellers, descended into a thick brown haze, the result of massive blazes burning up the Wasatch and Dixie National Forests below us. The airplane cabin was designed with one seat on either side of the aisle, for a ten-passenger capacity. When we weren’t leapfrogging over clouds, the stewardess would squeeze by, asking if we needed anything. I’d smile, shake my head, and pretend I wasn’t in the throes of mortal fear. I kept a United Airlines sick sack by my side at all times, and I closed curtains in a fruitless attempt to ease my terror of heights.

“Ladies and gents,” crackled the pilot’s voice through a loudspeaker overhead. “We regret the bumpy skies, but we should be past them very soon.…”

That’s what he said he over Nevada, I thought. Right then, the plane shook violently, to show me who was boss. I gave the sick sack a squeeze.

“It’s the safest form of travel, you know.”

I looked across the aisle at Sarah Jane, who licked her finger and turned the page of her book. She had inherited her mom’s features: hazel eyes, a narrow nose, a light sprinkling of freckles on her cheeks, and chin-length golden-brown hair. She mouthed the words as she read them, and no matter how often the plane shook and rattled, she never once averted her eyes from her book. She showed no hint of fear. How did she do it?

“Come again?” I asked.

“Airlines. Your odds of dying in a car wreck or a train jumping the tracks are a lot higher than in a plane crash.”

“Let’s change the subject, why don’t we. What are you reading?”

She pressed her finger between the pages to hold her place as she closed the book and held it up so I could see the cover. Little Women, said the gold engraved lettering, and below: Louisa May Alcott. I made a long face and tilted my head. “Isn’t this the third time you’ve read it?”

“Fourth,” she said, opening it to where she left off. “I read it again in May, for Mrs. Wells’s class. This trip makes four.”

I bobbed my head, doing my best to ignore the roller-coaster ride that was this flight. “Four times. That’s good. You must really love it, if you’ve read it four times.”

The ceiling speakers hissed and spat and the pilot’s voice came on: “We will be landing at Salt Lake Municipal Airport shortly. Those of you sitting on the right-hand side of the plane will marvel at the picturesque view of the city.”

Sarah Jane nudged me. “Open the curtains, Dad.”

“I’d rather not.…”

“C’mon. Have a look. You’ll feel better.” She tipped her head at the window. “Go on. Do it.”

With a trembling hand, I slid open the gray curtain and gazed out. It all appeared so small, that patchwork quilt of earth below, with a surprising number of green squares for a city at the desert’s edge. Mountains hemmed in the valley like a fortress, except for the northwest corner, where the Oquirrh Mountains tapered off at the shores of the Great Salt Lake. Even from thousands of feet above the valley’s southern end, the downtown and the granite spires of the Salt Lake Temple on the northern side were clearly visible. The sixteen-story Walker Bank Building dominated the skyline, with its towering radio antennae andWALKER BANK spelled out in tall electric-lit words. From this distance, I could even see the giant white U built on the side of Mount Van Cott, a symbol of the University of Utah, whose campus of columned, ivy-covered buildings nestled against the Wasatch Range nearby. The airplane dipped lower, its winged shadow swimming over farms and rural roads in the valley’s middle. Wide streets intersected in a perfect grid originating from the downtown temple, a deliberate plan by Brigham Young and the early settlers of this place. Thanks to them, it is difficult—if not impossible—to get lost in Salt Lake City.

Parting those curtains worked wonders. The dread I experienced only minutes earlier eased. I uncoiled in my seat and loosened my hold on the armrests. The airplane still jumped about in the skies, but now that we hovered low over the city, it all seemed so much less perilous than before, perhaps because I knew my destination was right under me. Even though I grew up in the next valley to the south, Salt Lake City felt more like home than my actual hometown of American Fork. This is where I lived out my various roles as husband, father, police detective, and member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Salt Lake City greeted me like an old friend. Salt Lake City, with streets so wide that back in pioneer times a team of four oxen pulling a covered wagon could make a U-turn with room to spare. Salt Lake City, home to ice cream parlors, movie palaces, and the most majestic state capitol building in the country, at the top of a hill overlooking the valley. Salt Lake City, where trolley bells rang like the heartbeat of a vibrant commercial center that a mere hundred years ago was uninhabited scrub. It all seemed so familiar, as if it were part of me, and I part of it.

“See?” said Sarah Jane.

“What?”

“I told you if you opened the curtains you’d feel better.”

“You’re right.”

“I know I’m right.” She smiled. “You think the firefighters have got all those blazes licked, Dad?”

I shook my head, craning my neck to get a better look at the swirling smoke clouds swallowing up the tops of the Wasatch Mountains. “Doesn’t look like it.”

“That’s too bad. Mary says half the state is burning up. Her uncle is a volunteer with the Provo Hook and Ladder.”

“That’s brave of him,” I said as we glided low over the airfield.

The airplane touched down on a dusty runway within sight of the Great Salt Lake. With propellers still roaring, it taxied past a cluster of arched steel hangars and some small wood-frame buildings that housed aviation schools and aircraft rental joints. It came to a halt near a new municipal terminal—built last year to attract visitors—where dozens of other airplanes were parked. I glanced back at Clara and Hyrum, both awake now and smiling, having slept the entire flight.

“Are we there yet?” said Hyrum, wiping cinders from his eyes. “That was fast.”

When the airplane stopped moving, unfastening seat belts clicked away and us passengers rose in unison, yet we all remained hunched thanks to the low ceiling. I pulled our luggage out of overhead compartments and the stewardess opened the door at the rear of the airplane. The kids were out of their seats first, scurrying toward the exit.

“I can’t wait to get home and try out that new hammock you got me for my birthday,” I told Clara as we inched forward, on our way to the oval-shaped doorway lit by sun. “The way I see it, it won’t hurt to miss one day of church.”

She shrugged. “Somehow, I get the idea Heavenly Father will forgive you. Last time you missed was back in twenty-seven, when you had whooping cough, and you only missed once, even though when you went the next Sunday you were still sick as a dog. You were hacking away in sacrament meeting. Remember?”

“Oh yeah,” I said. “I’ll take the rest of the day off, my last few hours of freedom before going back to work tomorrow. Live like a king.”

Bowing slightly to pass through the doorway, I maneuvered the two suitcases outside and clanked down the metal staircase. I reached the ground and beheld an unexpected scene: A massive crowd of Ovesons—my mother, three brothers, a trio of corresponding in-laws, and the hordes of children who accompanied them—blocked my way to the airport entrance. Big words in black paint on a homemade banner cried out, WELCOME HOME, RADIO STAR!!! They waved and cheered and erupted into “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” as I approached. Did I mention that there’s nothing Mormons love more than to show up at airports in big crowds to greet arriving family members?

Clara squeezed my elbow and I turned halfway to her as we crossed the sun-drenched tarmac.

“What was that about trying out your hammock and living like a king?” she asked, with a spirited laugh. “Looks like you’re going to have to take a detour through your hometown for Mom’s pot roast first.”

Copyright © 2015 Andrew Hunt.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Andrew Hunt is a professor of history in Waterloo, Ontario. His areas of study include post-1945 U.S. History, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and the American West. He has written reviews for The Globe and Mail and The National Post; two works of nonfiction, The Turning and David Dellinger; and is coauthor of The 1980s. His first novel in the Art Oveson series, City of Saints, was the winner of the Hillerman Prize in 2011. He grew up in Salt Lake City and currently lives in Canada.