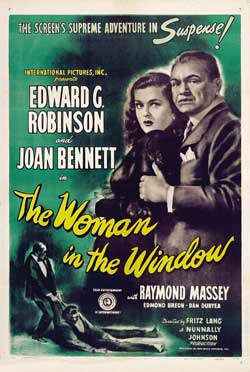

To celebrate the 70th anniversary of film noir’s landmark year, we’re looking at the six key noirs of 1944: Double Indemnity, Laura, Murder My Sweet, Phantom Lady, When Strangers Marry, and The Woman In the Window. Last week we looked at Robert Siodmak’s Phantom Lady. Today we look at Fritz Lang’s The Woman In The Window.

The Woman In The Window is the kind of film that comes right up to the edge of greatness and then swerves at the last moment. In a sense, that’s a shame, but look at it this way: most movies come nowhere near greatness.

The film stands at the crossroads in the career of star Edward G. Robinson. In the thirties, he had been one of the premier tommy gun-toting hoodlums at Warner Brothers, but in the forties, as the gangster picture gave way to the film noir, Robinson moved on to play a far different kind of character. In 1944, he made the pivotal Double Indemnity, playing the fast-talking insurance investigator. But that same year he made The Woman In The Window, the first of his middle-aged loser roles.

The film concerns a mild-mannered professor named Richard Wanley. He’s happily married to a frumpy wife and together they have a couple of contented-looking kids. When the family goes out of town for the week, Wanley meets some of the boys at the club for brandy and cigars. Life, he says with a sigh, is a little dull. The only hint of excitement is a new portrait of a woman in a gallery window next to the club. Wanley is staring longingly at this vision of beauty one night when the woman herself walks up to him on the street. Her name is Alice Reed (Joan Bennett), and if she seems overly impressed that the squat, mid-life crisis in front of her is smitten by her beauty, well, that only adds to the excitement. Soon, Alice has talked Wanley into joining her back at her apartment where they drink and smoke and talk the night away (while a large, soft-looking bed looms through the open bedroom door). Wanley is almost deliriously happy with this turn of events. Hell, who wouldn’t be?

The film concerns a mild-mannered professor named Richard Wanley. He’s happily married to a frumpy wife and together they have a couple of contented-looking kids. When the family goes out of town for the week, Wanley meets some of the boys at the club for brandy and cigars. Life, he says with a sigh, is a little dull. The only hint of excitement is a new portrait of a woman in a gallery window next to the club. Wanley is staring longingly at this vision of beauty one night when the woman herself walks up to him on the street. Her name is Alice Reed (Joan Bennett), and if she seems overly impressed that the squat, mid-life crisis in front of her is smitten by her beauty, well, that only adds to the excitement. Soon, Alice has talked Wanley into joining her back at her apartment where they drink and smoke and talk the night away (while a large, soft-looking bed looms through the open bedroom door). Wanley is almost deliriously happy with this turn of events. Hell, who wouldn’t be?

Then a cab pulls up in the rain and an angry man bursts through the door and demands to know what Wanley is doing in Alice Reed’s apartment. The man strikes Alice, jumps on Wanley and starts to choke him. Alice thrusts a pair of scissors into Wanley’s hand and he kills the man.

Now, in classic noir fashion, what started out as a possible night of adultery has become, in just a couple of minutes, a case of murder. Wanley and Alice decide not to call the cops for fear that they won’t be believed (and, it is implied, so that Mrs. Wanley will not be forced to wonder what her husband was doing in the younger woman’s apartment). Their attempts to dispose of the body, to avoid detection by a fast-acting police force, and to deal with a slimy blackmailer played by the prince of sleaze, Dan Duryea, form the bulk of the rest of the film. The movie proceeds in beautifully grim style right up to the final moments…

But more on that in a second. First, what must be acknowledged is the sheer skill on display here. The film was directed by Fritz Lang and demonstrates, once again, how early the great director got to the noir party. Of course, he’d been instrumental in developing the German Expressionism that preceded the noir era, and his early work in Hollywood (in films like the 1936 Fury) helped pave the way, but here we have Lang fashioning a fully developed film noir. It was perfect material for him, enlisting his skill as a pitiless observer of human weakness. Working with his gifted cinematographer Milton Krasner, Lang damn near nails down exactly what a film noir is supposed to look like with this movie. The Woman In The Window takes place in a 3 AM world of rain-slicked streets and cigarette smoke, a world where sexy young women and befuddled middle-aged men frantically debate how to best get rid of dead bodies.

The key performances here are from Robinson and Bennett. That same year, Robinson played a similar kind of role for laughs in Mr. Winkle Goes To War. It made sense, really. He had never been an imposing physical presence; as a thug, all he’d ever run on was crazy eyes and a fast mouth. Here is the Edward G. Robinson of noir, though: scared of sex, bewildered by age, wholly incapable of managing the situation he has stumbled into. His counterpoint is Joan Bennett. Beautiful, exuding fearlessness—she is not just a sexual fantasy, she’s a fantasy of youthful heedlessness. Against all reason, Bennett and Robinson are a perfect screen duo, the nightmare version of the May-September romance.

And yet, despite having all this talent marshaled to such great effect, The Woman In The Window misses greatness in its final moments with one of the worst endings in all of noir. Of this ending, I will say nothing more except that it ends this dark tale with a wink rather than a bang.

What I will point out instead is the happy fact that one year later this same creative team took up essentially the same material—middle-aged married dullard Robinson gets caught up with sexpot Bennett and slimeball Duryea—and brought it to glorious fruition with Scarlet Street. That film is an incomparable masterpiece, one of the premier works of noir art. The Woman In The Window, then, can be seen as an early draft, incomplete but fascinating in its own right.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of The Posthumous Man and Saint Homicide.

Read all posts by Jake Hinkson for Criminal Element.

The script was based on the novel Once Off Guard by JH Wallis. In 1949, Wallis also contributed the story to a fun little noir called Strange Bargain.

Jake, there’s no doubt that the ending to The Woman in the Window is really bad. But I’ve always suspected that the directive to do some kind of happier toned ending came down from the studio, that Lang couldn’t end it as he wanted to and so he purposely directed it to be ridiculous. The ending is so out of sync with the rest of the movie, it seems that Lang was trying to call attention to its absurdity, as if to say, “This doesn’t count, the real story with the real ending is everything you saw before this.”

I think you’re probably right, Scott. I have to think, too, that the greater creative freedom that he had on Scarlet Street–which was produced by the new company he’d founded with Bennett and her husband Walter Wanger–had a lot to do with why that film is pure hardcore noir right up to the closing frames.