I would love to do an experiment and have a person begin The Family of Pascual Duarte knowing just the title. There would be no cover photo, and the author's name would be blacked out. The reader would have none of the usual markers on which to base an expectation of what kind of book he or she is starting. Let's also assume that this person has a wide knowledge of genre fiction as well as so-called literary fiction. I would bet that when finished with the book and asked to describe it, this person would come up with words such as “dark”, “bleak”, “fatalistic”, “existential”. And the story itself? Well, it's about a man, Pascual Duarte, who tells us his tale in terse, blunt prose. The setting is Spain, from the late 1800s to 1937, and the story we're reading is supposed to be a manuscript Pascual Duarte wrote while awaiting execution in prison. The manuscript's dedication reads, “To the memory of the distinguished patrician Don Jesus Gonzalez de la Riva, Count of Torremejia, who, at the moment when the author of this chronicle came to kill him, called him Pascualillo and smiled.” Indeed, the book is a chronicle of a man who kills over and over again, both animals and people, and who has been condemned to death for his many crimes. His life takes place in a poor, rural environment, in harsh surroundings. There is no redemption at the end, no enlightenment of any kind, and so (this reader tells me) the book is probably best described as noir. In its stark pessimism, its depiction of a brutal unforgiving world, its portrayal of a criminal mentality, it is pure noir. Is the author known for writing noir? What other crime novels has the author done?

I would love to do an experiment and have a person begin The Family of Pascual Duarte knowing just the title. There would be no cover photo, and the author's name would be blacked out. The reader would have none of the usual markers on which to base an expectation of what kind of book he or she is starting. Let's also assume that this person has a wide knowledge of genre fiction as well as so-called literary fiction. I would bet that when finished with the book and asked to describe it, this person would come up with words such as “dark”, “bleak”, “fatalistic”, “existential”. And the story itself? Well, it's about a man, Pascual Duarte, who tells us his tale in terse, blunt prose. The setting is Spain, from the late 1800s to 1937, and the story we're reading is supposed to be a manuscript Pascual Duarte wrote while awaiting execution in prison. The manuscript's dedication reads, “To the memory of the distinguished patrician Don Jesus Gonzalez de la Riva, Count of Torremejia, who, at the moment when the author of this chronicle came to kill him, called him Pascualillo and smiled.” Indeed, the book is a chronicle of a man who kills over and over again, both animals and people, and who has been condemned to death for his many crimes. His life takes place in a poor, rural environment, in harsh surroundings. There is no redemption at the end, no enlightenment of any kind, and so (this reader tells me) the book is probably best described as noir. In its stark pessimism, its depiction of a brutal unforgiving world, its portrayal of a criminal mentality, it is pure noir. Is the author known for writing noir? What other crime novels has the author done?

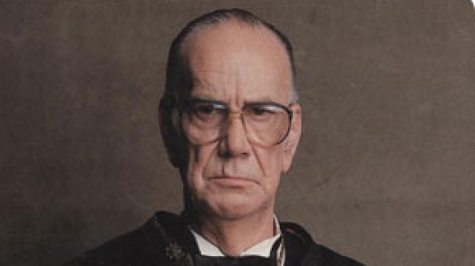

That's when I'd come clean. I'd reveal that the author is the Spanish novelist Camilo Jose Cela (1916-2002) and that he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1989. He published some seventy books: novels, short story collections, travel diaries. When he won the Nobel Prize, the Nobel jury described The Family of Pascual Duarte as the most popular work of Spanish fiction since Don Quixote, but in most of his novels, Cela is known for difficulty and experimentation. No one would confuse his books for genre works. He's a writer considered one of Spain's greatest during the 20th Century, yet if you pick up The Family of Pascual Duarte knowing none of that, to call it noir seems right on target. It starts out fucked and then gets worse. That's an old definition of noir, and it describes Cela's novel to a tee.

We get a sense of Pascual Duarte's worldview in the opening paragraph:

I am not, sir, a bad person, though in all truth I am not lacking in reasons for being one. We are all born naked, and yet, as we begin to grow up, it pleases Destiny to vary us, as if we were made of wax. Then, we are all sent down various paths to the same end: death. Some men are ordered down a path lined with flowers, others are asked to advance along a road sown with thistles and prickly pears. The first gaze about serenely and in the aroma of their joyfulness they smile the smile of the innocent, while the latter writhe under the violent sun of the plain and knit their brows like varmints at bay. There is a world of difference between adorning one's flesh with rouge and eau-de-cologne and doing it with tattoos that later will never wear off…

He launches into the telling of his life, saying the village where he was born “lay…squatting athwart a road as empty and endless as a day without bread.” He comes from an isolated environment where families have lived for generations and the hands on the town hall clock “were stopped forever at nine o'clock, as if the town had no need of its services but only wanted it for decoration.” People in this sunlit place have livestock and grow crops so nobody outright starves, but beyond the essentials nobody has much, and Duarte makes it clear that the atmosphere is oppressive. Is it any wonder that some people, for whatever reason, simply don't fit in? Duarte tells us that from an early age he liked fishing and hunting, but something about his laconic voice feels off. Maybe it's the way he focuses so much of his attention on morbid details. There's the way he luxuriates in his family stable's foul smells, and there's his attraction to decomposition:

It was dank and dark, and its walls reeked with the same stench of dead beasts as rose from the ravine in the month of May, when the carcasses down below began to turn into carrion while the crows swooped to feed…

It is a strange thing, but if as a child I was taken out of range of that stench I felt the anguish of death.

That’s the beginning of the signs of an odd young man headed for trouble. And by the end of the story's first section, Pascual has committed his first crime, the killing of his faithful and affectionate dog:

Suddenly a shudder ran through my whole body. It was like an electric current that was trying to discharge itself through my arms and ground itself in the earth. My cigarette had gone out. My gun, a single-barreled piece, was between my knees and I was stroking it. The bitch went on peering at me with a fixed stare, as if she had never seen me before, as if she were on the point of accusing me of something terrible at any moment, and her scrutiny roused the blood in my veins to such a pitch that I knew the moment was near when I would have to give in. It was hot, the heat was stifling, and my eyes began to close under the animal's stare, which was as sharp as flint.

I picked up my gun and fired. I reloaded, and fired again. The bitch's blood was dark and sticky and it spread slowly along the dry earth.

This pointless act, committed under the influence of the heat, brings to mind Mersault's murder of the Arab in Albert Camus' The Stranger. And it's no surprise that Cela's novel has been compared to Camus'. The two books were published the same year, 1942, and both are existential primers told by unrepentant killers awaiting execution. But whereas Mersault has a clipped voice, a rather tough voice (itself modeled on hardboiled/noir writers like Dashiell Hammett and James M. Cain), Duarte's tone is a bit mocking and cynical. And Duarte is more engaged with life than Mersault is. He provides what comfort he can to a mentally deficient baby brother, loves his younger sister and tries to protect her from her abusive pimp, marries a woman after he gets her pregnant because he thinks it's the right thing to do. As he says, “…it is never out of place to be kind.” But try as he might, no matter what choices in life he makes, he knows something will trip him up in the end. Listen to him as he approaches his wedding:

For my part I can say there were times I thought I'd lose my mind thinking about what was going to happen. Perhaps somehow I'd gotten the scent of my own undoing. The worst of it was that my sense of smell didn't assure me that my fate would be any better if I stayed single.

The baby his wife gives birth to dies at eleven months old, the victim of an ill-wind, an evil draft. Nature, too, does humans no favors. Duarte knows that the “road to disaster was the only path my dogged footsteps could travel through all my sad days…”, but as he says himself, “a self-respecting man can not let himself be overcome by tears”. As for life and his place in it, at the very least he has a sense of self-awareness. He has no illusions about his nature:

…And anyway I'm not made to philosophize, I don't have the heart for it. My heart is more like a machine for making blood to be spilt in a knife fight…

And why should he go against his nature? Has life taught him that anything changes if he keeps himself in check?

There's matter for thought in the fact that on the few occasions in my life when I decided not to act too badly, my evil fate, the evil star I mentioned before, took special pleasure in dogging me. It blighted everything so thoroughly that not a single good deed was of any use whatsoever. Worse than that: not only was anything that might be called good of no earthly use to me, but it was always so warped and twisted that in the end it only made matters worse.

Violence is the one thing that brings Duarte relief. He explodes when the anger inside is too much. I wouldn't go so far as to call this book a psycho noir in the Jim Thompson tradition, but Cela's novel is definitely a forerunner of that type of narrative. Duarte is not a scheming sort of person, but he is skewed and amoral enough to be called sociopathic, not to mention homicidal:

A man kills without thinking. Sometimes, even without wanting to. A man hates, hates profoundly, ferociously, and he unclasps a knife. Carrying it open and heavy he goes in bare feet toward the bed where his enemy sleeps. It's night, but the light of the moon comes spilling through the window, and he can see what he's doing. There's a corpse on the bed, someone who's going to be a corpse.

He leaves a number of corpses behind him in this book, and his next-to-last murderous act constitutes a very specific abomination. It's a chilling scene. A postscript by the transcriber of his supposed manuscript reminds us that Duarte also killed the man his account is dedicated to. Why he committed this last crime is left to speculation, and the book ends on a wonderfully ambiguous note: here was a man who lived as he lived and did as he did, and even though he told the story himself, who can ultimately answer the question of what made Pascual Duarte the person he was. It's an unsettling conclusion, and a striking way to end the book.

At about 170 pages, told in direct plain language, The Family of Pascual Duarte is a quick read. It locks you into its pitiless, doom-laden perspective and keeps you there. An unapologetic murderer is our guide. Is the novel pulp fiction? Not exactly. Will you find it in the crime fiction section of your bookstore? Never. But don't let the book's literary reputation fool you. This particular classic is noir.

Scott Adlerberg lives in New York City. A film nut as well as a writer, he co-hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series each summer at the HBO Bryant Park Summer Film Festival in Manhattan. He blogs about books, movies, and writing at Scott Adlerberg’s Mysterious Island. His Martinique-set crime novel, Spiders and Flies, is available now from Harvard Square editions at Amazon, B&N, and wherever books are sold.

Excellent piece, Scott. This book is new to me, so thanks for the introduction.

My thoughts follow Jake’s, Scott. It sounds like my kind of read and Cela sounds like he was a fascinating character.

Great article. Thanks.

Edward, glad you enjoyed the post. Yeah, Cela was quite a guy. He spent his entire writing life in Spain, through the whole Franco era, and found a way to shadowbox through everything. He was apparently loyal to the Franco regime, but sometimes he got in trouble with the censors. Some of his books were banned in Spain. After Franco died and things loosened up, he loved to stir up trouble and scandal. The dedication he put in a later edition of PASCUAL DUARTE says, “I dedicate this 13th and final edition of my Pascal Duarte to my enemies, who have been of such help in my career.” He seemed to be having his fun through everything. Gotta like that.

You convinced me, Scott. A copy of the book is on its way to me.

I think you’ll like it, Brian.

I’ve been reading it today. Superb novel.

Glad you enjoyed it, Brian.