All of that uninhibited freedom, though, has at times fostered a sense of lawlessness in San Francisco. For every sailor who awoke in a brothel in the Barbary Coast, another awoke on a ship, kidnapped by “Shanghai” Kelly; while the Beats were reciting poetry in North Beach, Sonny Barger was forming the notorious Oakland chapter of the Hells Angels; and as the hippies were frolicking in Golden Gate Park, the Zodiac Killer was tallying victims all across the Bay Area.

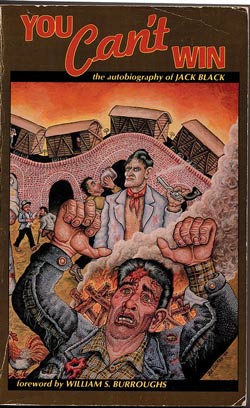

It’s not surprising, then, that two great crime books to come from San Francisco were written by authors with checkered pasts. You Can’t Win by Jack Black, and Shake Him Till He Rattles by Malcolm Braly, were penned by career criminals who straightened out in time to capture their respective eras in San Francisco history. Though written decades apart, the books share a voice that is particular to that of an ex-con. It is a voice that is tough yet empathetic, unflinching yet forgiving. It is neither self-pitying nor self-flagellating. It is the voice of a life lived hard.

You Can’t Win, first published in 1926, is the autobiography of Jack Black, who was at various times a burglar, a convict, a dope fiend, a “yegg,” and a member of the Johnson Gang of thieves. Black crisscrossed the country at the turn of the 20th century, learning his craft (thieving, not writing) from a cast of characters so vivid, their names alone will make you smile: The Sanctimonious Kid, Salt Chunk Mary, Sticks Sullivan, Foot-and-a-half George, and Montana Blacky, to name just a few. After many visits to San Francisco, Black eventually settled down in the city, his decision no doubt influenced by his stay in nearby San Quentin prison.

You Can’t Win, first published in 1926, is the autobiography of Jack Black, who was at various times a burglar, a convict, a dope fiend, a “yegg,” and a member of the Johnson Gang of thieves. Black crisscrossed the country at the turn of the 20th century, learning his craft (thieving, not writing) from a cast of characters so vivid, their names alone will make you smile: The Sanctimonious Kid, Salt Chunk Mary, Sticks Sullivan, Foot-and-a-half George, and Montana Blacky, to name just a few. After many visits to San Francisco, Black eventually settled down in the city, his decision no doubt influenced by his stay in nearby San Quentin prison.

Open to any page in You Can’t Win and you will see why it was the favorite book of William S. Burroughs, who wrote the introduction for the AK Press reissue. Black’s teeming prose, his rat-a-tat-tat rhythm, and his use of street slang are obvious influences on the Beats, especially Jack Kerouac. You Can’t Win is also stuffed with delightful old time colloquialisms: professional thieves were “yeggs,” cops were “bulls,” opium was “hop,” and everyone was addressed as “kid,” no matter their age.

Black tells us at the beginning of the book that he is going to write about the things he stole during his life as a thief just as he took them, “with a smile.”

Black makes good on this promise, describing a life filled with one hardship after another, beginning with the death of his mother at age ten. He is then shuffled to an orphanage until age 14, when he is let out into the world alone. For the next thirty years, Black alternates between the life of burglar and that of an inmate.

Black’s story would make you cry, if only he let you. But Black never lingers on any of these grim episodes for too long, and he never allows self-pity to overwhelm him. It is this unyielding spirit that resonates long after the details of Black’s life become fuzzy. Like the way he responds to the various abuses he endured in prison, including lashings, weeks of solitary confinement in “the box,” and the one that almost broke him, being placed in a straightjacket:

I’ve heard a lot about the humiliation and degradation of flogging. If anybody was humbled and degraded in my case it was not I. It may sound strange when I say I am glad now, and was glad then, that they lashed me. It did me good. Not in the way it was intended to of course, but in a better way. I went away from the tripod with fresh confidence, with my head up, with a clear eye and mind, and sustained with a thought from the German, Nietzsche, “What does not kill me strengthens me.”

Remind me to adhere to Black’s outlook on life the next time the barista at Peets screws up my coffee order.

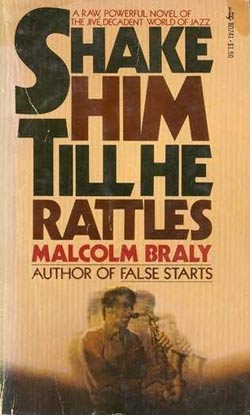

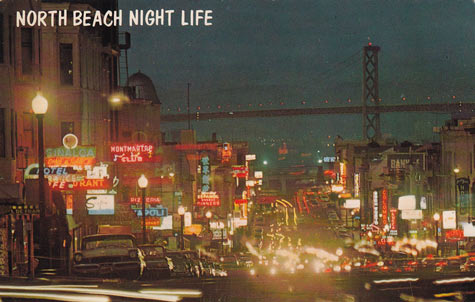

Shake Him Till He Rattles (1963) jumps forward a few decades to when the Beats prowled the streets of North Beach. Lee Cabiness, the protagonist of Shake, is a saxophone player who only wants to blow his horn without regard to money or career. He is thwarted in this simple pursuit by Lieutenant Carver, the local police bully who wants to take North Beach back from the Beats and reclaim it as the “fine Italian neighborhood it once was.” Carver’s initial attempt to strong arm Cabiness into becoming a drug informer fails, and Carver vows to take revenge on Cabiness by any means necessary.

Shake Him Till He Rattles (1963) jumps forward a few decades to when the Beats prowled the streets of North Beach. Lee Cabiness, the protagonist of Shake, is a saxophone player who only wants to blow his horn without regard to money or career. He is thwarted in this simple pursuit by Lieutenant Carver, the local police bully who wants to take North Beach back from the Beats and reclaim it as the “fine Italian neighborhood it once was.” Carver’s initial attempt to strong arm Cabiness into becoming a drug informer fails, and Carver vows to take revenge on Cabiness by any means necessary.

Cabiness spends the rest of the novel dodging Carver with his sidekick Furg, being seduced by a rich girl slumming it in North Beach, and longing for his ex-girlfriend who may or may not have been turned out by a local pimp. He takes on all of this while deciding whether or not he wants to get serious about a career in music.

Shake is more consciously literary than You Can’t Win, but it documents the vibe of its era in much the same way. Instead of opium you have “stuff,” instead of bulls you have “narcos,” and in place of pimps you have “fish.” It’s “dragsville” when you have no “bread,” and everyone needs to “dig” something or other. It is a bohemian North Beach, where jazz can be heard at every street corner, where a drug dealer uses live geese as an alarm system, and where musicians pawn lawn mowers for twenty dollars.

But North Beach was more than just a physical location, as Braly makes clear. It was also an attitude. “This was the Beach. You didn’t take things big. Or, at least, tried to avoid that appearance—it wasn’t cool. And to be cool was both fundamental virtue and prime commandment.”

Cabiness tries to live up to this unemotional standard, but is called on it by Claire, the wounded rich girl using him for her boy toy. “Beneath that rhinoceros hide of yours, you’re a rosy-eyed romantic. You believe those things you play on your horn, and everything else you say and do is part of a lie, and it’s not even your own lie.” Claire’s assessment rings true for not just Cabiness, but for most tough guy protagonists in all of crime fiction.

While their prose and genres are different, Braly and Black share a tone that is a result of their years spent as criminals. For instance, when describing tragic events, they are never overly sentimental. Like when Black’s best friend is shot in the face in a burglary attempt, Black offers only this brief account, “A twitching shudder ran through him. He straightened out his body and threw his arms wide. He was dead.” Similarly, after Cabiness’s best friend dies in a drug overdose, Cabiness snaps the dead man’s girlfriend out of her hysteria with this simple statement of fact, “(Cabiness) pointed at the blanket. ‘That’s not Furg,’ he told Ann. ‘Furg’s gone.’”

But Braly also shares Black’s forgiving nature. When given the opportunity to avenge Carver, a man who more than deserves avenging, Cabiness cannot go through with the plan. “He’d never imagined it would be difficult to step on a spider, but when the spider moaned and scuttled, broadcasting its pain, it was different. He couldn’t do it.”

I suppose it’s not surprising that two ex-cons would write so matter-of-factly about the depravity of the world. What is surprising for me, though, was how these authors could endure that depravity and yet still write books that are so joyful and life affirming.

Leading image from foundsf.org

Court Haslett is the author of Tenderloin, a crime novel set in 1970's San Francisco. You can follow him on Twitter @courthaslett and at The Rouge Reader

Thanks for a great post. I live near San Francisco and didn’t know this.

I was 30 years old and on my last year of my fourth term when i read you can’t win. I had been roughed up pretty bad by the cops this time Wich almost left me paralysed. Wrongfully suspected of possessing drugs i was convicted only of resisting arrest ironically posses. became a misdomenor here anyway. Like Black i was paroling “hating anything bigger than a grasshopper” and hell-bent on causing as much destruction as i could. Then something happened just like it happens in the book- kindness. Ten years of incarceration did me just as much good as it did Jack…so did one act of kindness and someone caring.I haven’t had any run ins with the law in 5 years now. I hope Californians read this story.