Bligh and his men, for all intents and purposes having been condemned to death on the open water, made an astonishing 3,618-mile journey to the East Indies. Meanwhile, after fleeing Tahiti with some local women and supplies, Christian and a handful of his mutineers disappeared.

Somehow, of all the many mutinies in naval history, the story of Bligh, Christian, and the HMS Bounty took on the quality of a myth. In some respects, this is baffling. After all, the mission of the Bounty and its crew was hardly the stuff from which legends spring. Bligh’s job was to go down to Tahiti to pick breadfruit plants that would then be used as an inexpensive food source on West Indian sugar plantations. In other words, the Bounty was transporting cheap groceries in support of the slave trade.

In addition to the grimy nature of the mission, the ship and her men were all less than impressive. The Bounty itself was so small that the captain had to give up his quarters to make room for the breadfruit. Bligh seemed to be stuck in a go-nowhere job, with his middle age fast approaching, and his professional options dwindling. (“Captain Bligh” wasn’t even technically a captain; he was a lieutenant.) His crew was a ragtag group. Some like Fletcher Christian came from good families that had fallen on hard times. Many others were scared-up, toothless seadogs.

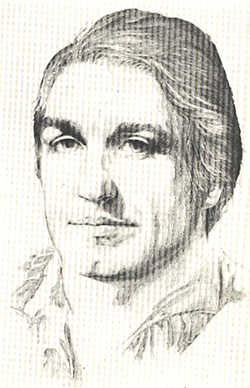

So why did this insignificant incident became the mutiny of all mutinies? The main reason has to do with the starkness of its central story: a group of Romantic Era sailors depart from England in a cramped ship, discover the sensual freedoms of the Tahitian island, and then rebel against the strict discipline of the navy. They sail away, disappearing into the fog of time.

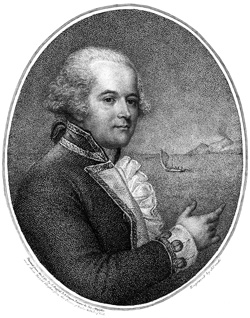

Part of the appeal is to be found in the central characters. William Bligh—the name itself sounds like a disgusted ‘blah’—the man of rules and regulations. When he and his starving loyalists completed their brutal open-boat voyage to Timor, he briefly became a national hero. (One fact beyond dispute in this whole affair is that Bligh’s successful navigation of his battered little lifeboat is one of the greatest feats in naval history.) Over time, however, he became the villain of the story—the tyrant with a lash in his hand and abuse on his tongue. As the writer Caroline Alexander convincingly argues in her brilliant 2008 book The Bounty, this view of Bligh—repeated in histories, novels, plays, and films—is little more than slander. While he was as strict a disciplinarian as most ship captains, Bligh was hardly a tyrant. One point Alexander establishes very well is that fully half of the Bounty’s crew elected to climb into the little lifeboat with their captain—so many, in fact, that there wasn’t enough room for every man who wanted to stay with Bligh.

The third act of the Bounty saga is equally fascinating. Years after the Bounty disappeared, an American naval vessel happened upon an island inhabited by one white man, a few Tahitian women, and a handful of children. The man gave his name as John Adams, the last surviving mutineer of the Bounty. After leaving Tahiti, Adams explained, the mutineers had struck out looking for an island mentioned in one of Bligh’s books, an island the exact coordinates of which were unknown. By sheer luck, or happy fate, they stumbled across the lush, isolated Pitcairn’s Island. When divisions arose between the mutineers and the Tahitian men they’d brought with them (according to Adams, the Englishmen regarded Tahitian women as wives, but Tahitian men as little more than slaves), the resulting battles killed every grown man save for Adams. Among the children was Thursday October Christian, the son of Fletcher Christian and Maimiti, and the first child born on Pitcairn. The island today is still inhabited by the descendants of the Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian wives.

Over the years, the mutiny has found its way into many books and films. Here’s a quick guide to a few:

1. The Bounty Trilogy (Mutiny On The Bounty, 1932; Men Against The Sea, 1933; Pitcarin’s Island, 1934) by Charles Nordoff and James Norman Hall—a rollicking adventure series full of action and romance, but marked by a wild caricature of the “villainous Bligh” and compromised by casual racism and anti-Semitism.

2. Mutiny On The Bounty (1935)—Adapted from Nordoff and Hall, this classic adventure stars Charles Laughton as Bligh and Clark Gable as Christian. Highly entertaining, a perfect example of the simplified revolt-against-tyranny version of the myth.

3. Mutiny On The Bounty (1962)—A brooding, downbeat version of the saga starring grim Trevor Howard as Bligh and a somehow even grimmer Marlon Brando as Christian. Not much more historically accurate than the ’35 version and not as much fun.

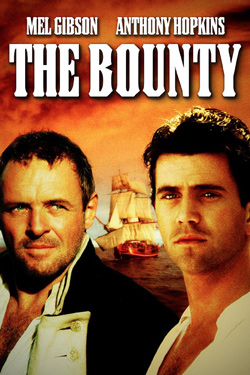

4. The Bounty (1984)—By far the most historically accurate adaptation of the story, this Roger Donaldson film is also the best. Starring Anthony Hopkins as Bligh and Mel Gibson as Christian, the movie abandons the tyrant/rebel dichotomy of earlier versions in favor of a more nuanced, and more interesting view of the conflict. Supporting Hopkins and Gibson (both of whom are excellent) is a Who’s Who of acting talent: Daniel Day-Lewis, Laurence Olivier, Liam Neeson, and Edward Fox.

4. The Bounty (1984)—By far the most historically accurate adaptation of the story, this Roger Donaldson film is also the best. Starring Anthony Hopkins as Bligh and Mel Gibson as Christian, the movie abandons the tyrant/rebel dichotomy of earlier versions in favor of a more nuanced, and more interesting view of the conflict. Supporting Hopkins and Gibson (both of whom are excellent) is a Who’s Who of acting talent: Daniel Day-Lewis, Laurence Olivier, Liam Neeson, and Edward Fox.

5. The Bounty: The True Story Of The Mutiny On The Bounty (2008) Caroline Alexander—There are several good books on the Bounty saga, but this is the first one to get. Deeply researched, cogently argued, and beautifully written, it’s the definitive account of the events leading up to, and out of, that fateful April morning.

Jake Hinkson, the Night Editor, is the author of The Posthumous Man.

Here’s a cool [url=http://www.lonelyplanet.com/pitcairn-island/videos/the-bounty-mutineers-pitcairn-island$lptv_pitcairn]video tour[/url] of Pitcairn’s Island by travel writer Celeste Brash.