Why are we still so fascinated with Leopold and Loeb? It’s been nearly a hundred years since they murdered a fourteen-year-old named Bobby Franks, but we’re still talking about the case. Numerous books have been written about them and nearly as many movies have been inspired by their crime. As recently as 2005 there was an Off-Broadway musical about them. What’s the appeal?

There’s no complete answer to that question, but it hasn’t stopped filmmakers from asking. Alfred Hitchcock freely adapted the story in his 1948 Rope, starring John Dall and Farley Granger as the killers. While the results are entertaining, there’s a curious disconnect in the film that is only exacerbated by the fact that Hitchcock used the project largely as a way to experiment with continuous long takes. Though Rope was told from their point of view, Hitchcock completely skirted the issue of sex between the two men (Leopold and Loeb were lovers), depriving us of an important layer of their relationship. Of course, 1948 being 1948 there was only so much a film could even imply, but Hitchcock didn’t find much to substitute in the absence of the sexual power dynamics.

In contrast, Tom Kalin’s 1992 Swoon might be seen as a swing in the opposite direction. Coming at the forefront of the New Queer Cinema movement, Swoon put the relationship between the killers at the center of the story. While fascinating in many respects—with several haunting passages augmented by beautiful black and white cinematography—the film doesn’t really develop Leopold and Loeb beyond a broadly sketched sexual tug-of-war.

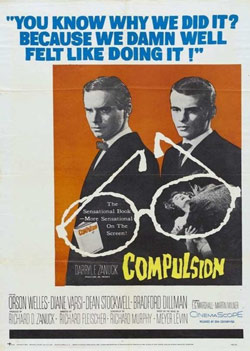

The film made from his book is a surprisingly intelligent and frank treatment of their case. Compulsion makes no real effort to disguise the fact that the young men were lovers, and it explores the psychosis of their relationship vividly. Leopold (for clarity’s sake I’ll use the real names of the killers) is played with an icy fragility by Dean Stockwell. He’s brilliant, knows seventeen languages and can already outdebate his professors on Nietzsche’s concept of the “superman,” that superior individual not bound by normal notions of morality. Leopold maybe half a genius, but he’s also helplessly in love with Loeb, played by Bradford Dillman as a pampered, coldhearted psycho. Leopold has the intellectual concepts, but Loeb has the real ice in his veins. If the idea of romance is that two lovers complete each other, the exact opposite seems to have been the case with Leopold and Loeb. At least as they are presented here, neither of these guys could have killed someone alone, but together they were able to cancel out each other’s humanity. Drunk on a mix of narcissism and philosophical delusion, they became one giant id. As the young killers, Stockwell and Dillman are excellent, and their scenes together are intense, intimate, and chilling. Had the film stayed with these two guys it might very well have been a masterpiece.

As we start to focus on Welles and his legal tactics, however, Compulsion loses its power. The first hour of the film is an uncommonly intelligent and disturbing film noir, followed by thirty minutes or so of a routine courtroom drama. The movie more or less abandons the two killers at the start of the trial, in much the same way Leopold and Loeb were overshadowed for a while, obscured by the light shining on their celebrity lawyer. But just as in real life, we return to them when the movie is over and ask ourselves the same urgent, unanswerable question: how could they have done this terrible thing?

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of Hell on Church Street.

For more on the trial, read the overview at [url=http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/leoploeb/leopold.htm]Famous Trials[/url].

Thanks for this article. The Booby Franks murder, the Lindberg baby kidnapping and the Sacco and Vanzetti trial are each memories from my childhood. All happened long before I was born but all came up time and time again in the pop culture of the 1950s.

Orson Welles was hired as an actor on the film, but according to TCM’s Robert Osborne (who was on set) Welles was allowed to direct most of the courtroom scenes in that last half of the film. (With the director’s blessing!)

I lived in Puerto Rico in 1969 and had Nathan Leopold as an Algebra teacher at the Commonwealth High School. Being a poor math student, he tutored me during the 1969 school year. I even have his autograph in my yearbook. His past eventually came to light to the administration of the school, and he was released as a teacher. I found him to be a quiet and thoughtful man, never realizing who he was until years later.

AR-

Thanks so much for the comment, and for sharing your memory of Leopold. That’s fascinating.