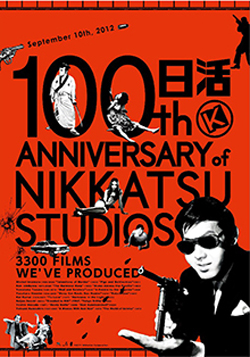

Japan’s output of neo-noir (particularly from Nikkatsu, which was like the RKO of the Asian film industry) was an idiosyncratic blend of yakuza gangster picture and classic film noir. Its most famous practitioner was the wild man of Japanese noir, the director Seijun Suzuki, whose films pushed the envelope (well, destroyed the envelop and set it on fire, actually) not only of decorum and good taste but also of coherence and film language. Suzuki was hardly alone in walking the mean streets, however. What follows is a brief overview of the dark and twisted world of Japanese noir.

A Colt Is My Passport (1967)

This underrated yakuza picture stars Joe Shishido as a hit man hired by one gangster to eliminate the boss of a rival gang. When things go awry, as these things tend to do, Shishido ends up having to fight both gangs. Directed by Takashi Nomura, this movie is an excellent place to start your plunge into Japanese noir. Though it culminates in a big action finish, it’s a curiously contemplative action picture. It will also introduce you to Shishido, the Robert Ryan of Japanese noir. Puffy-cheeked and laconic, Joe the Ace, as he was known, is the dominant actor of the genre and this is probably his best performance.

Take Aim At The Police Van (1960)

Here here you have an early Seijun Suzuki picture, reminiscent of those two-fisted Phil Karlson noirs like Kansas City Confidential and 99 River Street. Michitaro Mizushima stars as the guard on a police van who goes looking for the sharpshooter responsible for killing two of his prisoners. Not insane like other Suzuki films, Take Aim is straight-ahead hardboiled fun. Mizushima also starred in the early Suzuki flick, 1958’s Underworld Beauty.

Youth of the Beast (1963)

Suzuki and Joe the Ace team up for this ultra-violent gangster picture about a thug-for-hire (played by Shishido) who works his way into two rival factions and then turns them against each other. If that sounds close to the plot of A Colt Is My Passport, rest assured that the similarities end there. Here we have Suzuki in full flower, painting in vibrant colors and explosive images, shaking off the confines and restrictions of classic noir and embracing a new staggeringly original style.

Tokyo Drifter (1966)

Suzuki delivers what I would argue is his masterpiece. It’s part gangster film, part noir, part musical, part drug trip. Handsome and brooding Tetsuya Watari stars as a yakuza henchman who tries to turn legit but has to go on the run when some old enemies try to kill him. Not for everyone, this flick is full-tilt insanity from start to finish, culminating with a shootout that works like a kind of violent ballet. Quentin Tarantino has said that he wasn’t particularly inspired by Suzuki when he made the Kill Bill movies, but seeing this film makes the comparison inescapable.

I Am Waiting and Rusty Knife (1957, 1958)

Two early films written by Shintarô Ishihara, a fascinating figure in the early days of Japanese noir. Ishihara began as a novelist, writing the controversial novel Crazed Fruit and adapting it to the screen, thus helping to launch the “alienated youth” genre in Japanese film. He would later go into politics, becoming a hero of the Japanese nationalist right wing and serving several terms as the governor of Tokyo (a position he still holds). His late-’50s work in noir is of the hardboiled potboiler school of screenwriting. I Am Waiting is a romantic gem about a washed-up boxer trying to rescue a nightclub singer from her gangster boss. Rusty Knife is a hardboiled tale about a couple of thugs who try to go straight only to find themselves hounded by the cops. Nothing groundbreaking in those storylines, of course, but these films are full-on classic noir. Both feature lush black and white cinematography and wonderful performances from Ishihara’s charismatic brother Yujiro and the gorgeous Mie Kitahara.

Cruel Gun Story (1964)

Joe the Ace is back as an ex-con drafted by a group of shady businessmen into a hit on an armored truck. Directed by the journeyman Takumi Furukawa, this isn’t the most graceful film ever made, but Shishido is in fine form. Look for a future essay on Joe, who really was, for all intents and purposes, the embodiment of the Japanese noir ethos. He deserves closer attention.

Kurosawa Noir

So far I’ve mostly recommended down and dirty B movies, but no introduction to the genre would be complete without a shout out to the occasional noir output of Japan’s most heralded director, Akira Kurosawa. Though better known for samurai flicks like Yojimbo and quiet dramas like Ikiru, Kurosawa put in his time in Noirville. His three most notable excursions into this territory were High and Low, about an executive who must negotiate with a deadly kidnapper; The Bad Sleep Well, about an ordinary man hunting down his father’s killer; and Stray Dog, about a rookie cop who loses his gun to a pickpocket on a crowded bus. All three films star Kurosawa’s frequent star Toshiro Mifune, and all three take the rough materials of crime pictures and use them for the stuff of powerful drama.

Branded To Kill (1967)

Finally, one can only close out an introduction to this genre with a mention of its most notorious film, Branded To Kill. Seijun Suzuki reteams with Joe Shishido for the thoroughly entertaining/perplexing/confounding story of a rice-sniffing hit man who screws up a job and winds up being hunted by his old bosses. If that plot sounds like the yet another variation on a well-worn tune, rest assured that the film itself is a wholly unique creation. Ultra-violent, borderline pornographic, and resolutely crazy, it was deemed so over-the-top nuts that it got Suzuki fired from the studio. If you Google “not for every taste” this is the movie that should pop up first. If that scares you, go watch some Kurosawa. If, however, that sounds like a great night of cinema . . . Well, you know who you are. If you ain’t seen this yet, get on it. It’s as insane as you hope it is.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of Hell on Church Street.

I should point out that every movie mentioned above is available in glorious form from the Criterion Collection. You can get them from Netflix and you and stream them on Hulu Plus.

Three great Japanese noir novels: Out by Natusuo Kirino, Ashes by Kenzo Kitakata, In the Miso Soup by Ryu Murakami.

The contemporary filmmaker Kiyoshi Kurosawa is terrific, though leaning a bit more towards horror than noir.

So glad you pointed out that they are available online. I look forward to rewatching some of my favorite films from Japanese noir. Great post, Jake! I’d love to read a post about the female protagonists of Japanese noir. My favorite actress from that era is of course Meiko Kaji in [url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUC2NCx4Xbg]Stray Cat Rock: Sex Hunter[/url].