The Getaway starts in prison. Scenes of star Steve McQueen running textile machines and clearing brush are filled out with real convicts from the Hunstsville, Texas, prison where they were shot, a fact that the viewer can intuit from the faces, movement, and body language of the men on-screen even without reading any of the thousands of pages that have been written about the movie; its star, Steve McQueen; and director Sam Peckinpah. Presenting that kind of naturalistic footage raises the stakes on a movie—will the fictional story live up to that level of presumed realism? And can an actor hold up his end, bringing a convincing presence when dropped into that kind of environment?

The Getaway starts in prison. Scenes of star Steve McQueen running textile machines and clearing brush are filled out with real convicts from the Hunstsville, Texas, prison where they were shot, a fact that the viewer can intuit from the faces, movement, and body language of the men on-screen even without reading any of the thousands of pages that have been written about the movie; its star, Steve McQueen; and director Sam Peckinpah. Presenting that kind of naturalistic footage raises the stakes on a movie—will the fictional story live up to that level of presumed realism? And can an actor hold up his end, bringing a convincing presence when dropped into that kind of environment?

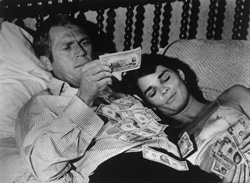

In the case of The Getaway, Steve McQueen is the perfect choice to bring off a character who has to seem at home in the world of violent criminals, realistically handling scenes of anarchic violence and high-stakes crime. McQueen had been raised by a part-time prostitute who had a string of violent boyfriends and who would abandon him for years at a time to relatives or the state. By his teens he was a truant and petty thief who had been in a series of foster homes and institutions. He credited an orphanage called the Boys Republic with giving him his only stable home, and was famous for demanding extravagant perks on set which (it was revealed years later) he donated to the home. A stint in the Marines burnished the persona of quiet power and physical competence that, coupled with ice-blue eyes and chiseled good looks, would make him the ’60s leading “anti-hero” and top box office draw.

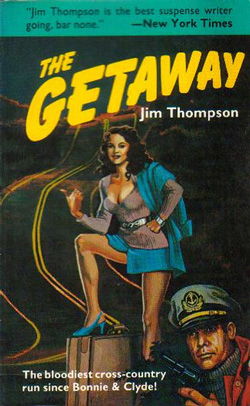

The Getaway’s source material is famous to fans of noir: the 1957 novel of the same name by Jim Thompson. The project had been through Sam Fuller’s hands before it ended up with Paramount’s Robert Evans. Evans and McQueen had first negotiated with Peter Bogdanovich, who was pulled in to another project, so McQueen turned to Sam Peckinpah, who had directed him in Junior Bonner the year before. Unknown to Peckinpah, McQueen retained the right to the final edit, and so the final product would owe a lot to his vision of the film.

Sam Peckinpah needed a hit. The hard-drinking director (a series of biographies leave the impression that he rarely passed a sober night during his adult life) was coming off the failure of Junior Bonner, the wistful story of a rodeo star in his declining years, and wanted to go back to the action films that had made him internationally famous. Peckinpah was also famous for rancorous, hard-drinking sets and fights with producers and staff (he fired 15 crew members during the shooting of Major Dundee, on which star Charlton Heston both threatened to run him through with a sword and worked without salary to keep the surly director on the project).

The concept of The Getaway may be Thompson’s, but Peckinpah’s imprint is on every detail, from the bloody, hard-edged violence, to the use of nonprofessional actors and authentic locations to ground the action, and the solid, dependable performances from Peckinpah’s stable of journeyman character actors: Ben Johnson as the manipulative, black-hatted Benyon; Bo Hopkins as Frank Johnson, the haplessly violent armed robber; and the menacing, unpredictable Rudy Butler, played by the seething Al Lettieri, who had just turned in a masterful performance as the antagonist of the Corleone family in The Godfather earlier that year.

Peckinpah’s insistence on realism would serve The Getaway well. During the shooting for his most famous film, The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah, dissatisfied with the “squibs” provided by his crew, the small explosives designed to portray bullet effects, reportedly grabbed a revolver and blasted live rounds at a nearby wall. He told the stunned crew, “That’s the effect I want.” Peckinpah insisted on recording the actual sounds of the different guns being used, a revolutionary demand in an age when studios typically used the same pallid “bang, bang” noise for all guns fired, regardless of the type. Peckinpah had also pioneered a technique of quick cuts and slow-motion images that accelerated the momentum of violent scenes while increasing their impact with audiences.

The Getaway was a commercial success and is a still a touchstone for fans of action films. McQueen’s seemingly effortless command of the screen and his fluid physical grace still work perfectly in the context of Peckinpah’s minutely orchestrated violence. It has been remade (badly) and referenced by many other heist films. Movies like Heat, Reservoir Dogs, City of Industry, and The Town all owe something to Peckinpah, and the admirers and imitators of Jim Thompson are legion. The influences of the creators and stars of The Getaway can be felt, subtly or not, every time the plot turns on a daring robbery, duplicitous accomplices, faithless lovers, and a briefcase full of money.

Dennis Tafoya is the author of two critically acclaimed novels, Dope Thief and The Wolves of Fairmount Park, and numerous short stories appearing in collections such as Philadelphia Noir from Akashic Books. His work has been nominated for two Spinetingler awards and his novels have been optioned for film. His third novel, The Poor Boy’s Game, is due from St. Martin’s Press in 2013.

Thanks for the reminder of an excellent film and all the foibles of the folks associated with it. In spite of the reviews, I must confess that I really liked Junior Bonner. That movie came across as a tale that needed to be told.