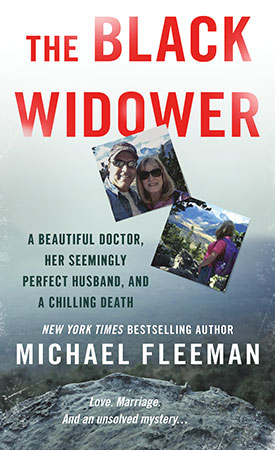

She was his second wife—to die…

Coming off a failed marriage, a beautiful woman named Toni joined an online dating site, hoping to find true and lasting love. Harold Henthorn seemed like her dream come true—a handsome man who said he had “a heart for others.” Only weeks after meeting, they were wed. But Toni’s family began noticing Harold’s dark side—especially his controlling nature, which Toni didn’t seem to mind. Until she met her end at the bottom of a ravine…

Was he a grieving husband—or a black widower?

Harold’s tearful story of his wife’s hiking “accident” just didn’t hold up with Toni’s family—or the police. Then a shocking truth was uncovered: twenty years before, Harold’s first wife had also died suspiciously in a remote area with no witnesses. Soon, more questions arose: Who was Harold Henthorn—a devoted, grief-stricken husband or a cold, calculating killer? Could authorities find a way to connect his wives’ deaths and expose the truth?

ONE

“911, what’s the address of the emergency?”

“Hello, my name is Harold Henthorn. I’m in the Rocky Mountain National Park. I need an Alpine mountain rescue team immediately.”

“What is your exact location?”

“My exact location is Deer Mountain near the summit about one mile south of the visitor center.”

Harold’s voice was urgent, but not hysterical. The cell phone reception came through crisp and clear.

It was 5:54 P.M. Mountain Time. He had reached the main Estes Park emergency dispatch center.

“I’m going to transfer you to the Park so hang on the line,” the operator said. “You’re going to hear some clicking. Right now, I’m calling on my phone here.”

As the sound of dial tones could be heard, Harold said, “I’ll tell you where I am,” but the operator instructed, “I’ll introduce who we are when they pick up the phone.”

She could then be heard telling another operator: “This is Estes and we have a gentleman on Deer Mountain. Go ahead, sir.”

“Thank you,” said Harold. “My wife has fallen from a rock on the north summit of Deer Mountain on the Deer Mountain trail. She’s in really critical condition. She’s had a bad fall.”

“How far did she fall, sir?” asked the new operator.

“Thirty, forty feet. Thirty feet.”

“Thirty, forty feet?”

“I think thirty feet.”

“Are you with her now?”

“I am,” said Harold. “Let me be sure you know my location first. I have really bad cell coverage. I’m on Deer Mountain near the summit. Not the normal regular northern summit, on the southern outcrop.”

“The southern outcrop?”

“If you look up south from the visitor center, there are two very large outcrops. We are not on either one of those two. We are between the two. Between the two outcrops that you can see from Fall River,” he repeated, then gave his location in latitude and longitude coordinates.

“Hold on for one second,” said the operator, who began talking to somebody else in the background. Harold’s breathing could be heard, slow and steady.

A different Park Service operator came on the line.

“OK, who am I talking to?”

This operator had a sharper, more businesslike tone. It was a busy night in the emergency dispatch center. The Park Service had waived the entrance fee this weekend and the crowds were large.

“My name is Harold Hill Henthorn,” he repeated.

“Are you with the patient?”

“Yes, I am, yes.”

“I already have rangers getting ready to come up there,” she said, and then tried to pin down his location further. “So you’re looking at Deer Mountain, you’re looking at two outcrops, and this person is between two outcrops?”

“Yes,” said Harold. “If you’re looking from the visitor center directly south, magnetic south, you’ll see two large outcrops about 9,000 feet. We are not on those two. We are between the two. About 200 feet off the crest of the hill.”

“And tell me some things about the patient,” she asked.

“She is a white female fifty years old, great health,” he said. “She had respiration approximately five to eight beats a minute, her pulse is about between sixty and eighty beats a minute.”

“And what’s her main injury?”

“Head injury. Concussion.”

“OK, any other injuries?”

“Could be internal—I don’t—.”

“Is she conscious, breathing?”

“No, she’s not. She has not been conscious. She is breathing. Anywhere between five and eight beats a minute now.”

“OK, hold on just a second.”

There was a pause, dead space for a few seconds.

Harold asked, “Can you hear me?”

“Yes,” said the operator.

“She is going to be evacuated from here,” Harold said. It came out as a statement, not a question. “Is there any way you can bring a helicopter in? A Flight for Life? There is a clearing about 200 meters south of me. There is this clearing where you could easily, easily—”

“Hold on,” the operator interrupted. “I’m on the radio.”

In muffled tones, the operator could be heard saying, “White female … not conscious … She is breathing.”

To Harold, she asked, “Are you a paramedic?” There was a touch of something that sounded like suspicion in her voice.

“No, I’m not, no,” he said, then mumbled something about being “with Civil Air Patrol.”

Harold appeared to grow impatient. “Let me be sure you know exactly where I am,” he said, his voice sharper, “because trying to get a ranger here is going to take you at least an hour on the AT trail.”

“Hold on, hold on, sir!” the operator interrupted again. “They’re talking to me on the radio.” She then asked Harold if he and his wife were engaged in “technical rock climbing.”

“We were not climbing,” Harold answered, “but you’re going to need an Alpine mountain rescue team from where we are right now. Let me ask you a question: There is a clearing about 200 meters south of me.”

“Hold on,” said the operator again, still on the radio.

“You could easily—” Harold started, but the first operator came back.

“Sir, I’m sorry, there are only two of us here today, and we’re kind of switching you back and forth, but I know what’s going on.”

“Here’s the thing,” said Harold. “I will pay any and all expenses for a helicopter. I don’t care if it’s private, I don’t care if it’s commercial. It wouldn’t matter if it was Medevac. I will pay any and all expenses right now if you drop a paramedic down here.”

“I understand that, sir. It’s really on the safety of everybody involved. So that will be up to the ranger in charge.”

“Weather’s good. There’s no wind whatsoever right now. Weather is excellent. Visibility is at least five to eight miles. There’s definitely—I’m not a paramedic, but you could safely drop a paramedic from a ten-foot rope. Easily, you could do that.”

“I understand, but they definitely need to probably get on scene,” said the operator. “They do have Hasty teams and those are the teams that are going to run up there if that’s possible and get to your location.”

“OK, our car is parked at the intersection of 34 [and] 36, our green Jeep,” he said, referring to the intersection of two mountain roads near the trailhead to Deer Mountain trail. “But it’s going to take an hour, a full hour to get here.”

“We definitely have people who are really fast on the trail and they’re in very great shape. Now talk me through—how did you get to that location?”

“We were just having lunch on the outcropping,” Harold said. “Not the two really steep ones, but a really nice outcropping. We come down a little further and, uh, she was trying to get a perfect picture, I think, and fell, and I came around, and she was unconscious. I came down and—”

“You were at Deer Ridge Junction, right, that’s where you parked?”

“Deer Ridge Junction, the intersection of 34 and 36.”

“And how far on the trail do you think you went?”

“We went to the actual summit.”

“The actual summit?”

“Not the summit on the south side—9,012-foot summit. We crested around there, came around the switchbacks, came up to where the Deer Mountain Trail levels off.”

“OK, so you went to the switchbacks where Deer Mountain Trail levels off?”

“We turned directly north.”

“Turned north, OK.”

“Went about maybe, you know, several hundred yards, and there you reach the north outcrops. We didn’t go to the really steep one that you can see from the visitor center or the one to the west of that. We were between the two.”

This meant that Harold and his wife had gone off the trail about 2.2 miles into the hike after making a steady incline as they passed meadows with views of Longs Peak and the mountains of the Continental Divide before reaching a junction where a series of steep sharp switchbacks led to the summit.

“How far from the top of the peak do you think you are?” asked the operator.

“We didn’t actually go to the peak. We were not at that area. We were in the saddle between those two and we came on down.”

“And if you look up at the peak, how far do you think you are from the peak?”

“I can see the top, maybe two hundred feet from the top.”

“Two hundred feet from the peak?”

That placed them somewhere before those switchbacks on the north side of the mountain overlooking the Fall River Valley and the Park Service’s Fall River Visitor Center and, to the right, the town of Estes Park.

“Yeah. They’re not going to see me from where the pine trees are grown out,” Harold said. “I’m not sure how long the cell coverage is going to be.”

“How much battery power do you have left, sir?”

“It’s not great,” he said. “What I can do is—I can’t imagine them being within an hour if they’re hiking from Deer Ridge. Worst case scenario, if we lose complete contact here, I’ve got a whistle someplace, I’ll blow that whistle every 15 minutes from the top of the hour, starting at 7 o’clock.”

It was now after 6 P.M. The almanac had sunset for 6:46 P.M. but the trees and high peaks would make it darker earlier.

“There’s no way you’ll be here before seven if you walk in,” Harold continued. “Again, if there’s any chance I can persuade you to think about a chopper, in this light wind. Normally in the park it’s just blowing like crazy. I will pay any expense.”

“They’re asking you to put as many bright items out as possible to see if they can’t see you,” said the operator. “Is anybody near you, sir?”

Harold didn’t answer. Instead, he said, “OK, I’m looking at the visitor center right now, and I’m flashing a mirror, but I can’t see the sun, so there’s minimal chance you can see this.”

“You’re in some pine trees there?”

“Pine trees, yeah. You’re not going to see anything. It’s too dark. I’m definitely now in view of the visitor center, to the magnetic north. Is there somebody at the visitor center?”

“You know, I’m not sure,” said the operator.

“I’ve got a purple bag. I’m moving a purple bag right now. I’m in the shadow.” There was now the sound of rummaging around.

Harold asked if the rescuers were driving to the highway junction where he parked.

“What’s that, sir?”

“They’re driving to the junction?”

A change had come to Harold’s voice. Annoyance crept in.

“I’m not sure if they’re there yet because I’m working on a different side of the Park,” the operator said. “Are you back with your wife right now?”

For several minutes now, Harold had not mentioned his wife or her condition.

“I’m right here,” he said. “I’m right with her.”

“How is she doing?”

“Her respiration is weaker,” he said.

“Her respiration is weaker?”

“Yeah, five beats a minute.”

It was the second time he made reference to “beats.” The operator didn’t seem to know what he meant.

“Five beats a minute?”

“Yeah.”

Then she asked, “Do you know how to perform CPR?”

“I do, I do,” he said.

Trying to assess the woman’s condition, the operator asked, “More about this fall, sir. Was it like a sliding fall or did she fall directly?”

“I didn’t see it exactly. I was messing with one camera, she was messing with the other one.”

“You didn’t see her fall?”

“I didn’t actually see. I saw the motion but I—”

“Do you have any flashlights?”

“Yes, I do. I do have one.”

“You have a flashlight. And how much battery power do you have on your cell phone?”

“Not much, half power.”

“I’m going to give you another number just in case we do get disconnected. Do you have something to write with or will you remember? Or you can call 911, and they’ll transfer you back to us”

“I’ll do that. That will be the fastest way.”

“Let me get your cell phone number, sir.”

He read it off to her. A 303 area code—Denver area. “And your name, please?” he asked.

“My name is Kelly.”

“Kelly. Thank you. Appreciate your help.”

“And there’s also an Elizabeth in here.”

“OK.”

The operator now explained why a helicopter couldn’t be dispatched. “I want to let you know, most of our helicopters are Medevac helicopters.”

“I understand.”

“They’re not really trained to do technical type things. They do land in certain areas.”

“You would not need technical to get to me,” Harold said.

“They can’t like drop somebody from the helicopter.”

“From a ten-foot rope?”

“No, sir, that’s not been done in my experience. But we do have EMT-qualified rangers.”

“I understand, yeah. It’s—She needs to get out of here. She needs to get to the hospital.”

What the operator didn’t tell him was that no civilian could order up a rescue helicopter. The risks to the crew were too high. Only a rescuer on scene could make that determination.

“And what is your name, sir?”

“My name is Harold Henthorn.” She asked him to spell it, he did.

“And your wife’s name?”

“Her name is Toni. T-O-N-I.”

“OK, and does she have any other health issues?”

“None at all. We were staying at the Stanley Hotel. She has no health issues at all. I’d better save the cell battery here.”

“Why don’t we do this,” said the operator. “I’m going to hang up with you and check with the ranger first to see if there’s any information that we need. We’re going to hang up, and you’re going to turn off your phone. I don’t know if it causes more battery power to turn it off and turn it on.”

“It’ll save the battery.”

“If you want to try to call us back in twenty minutes, if we set a time frame.”

“OK.”

“OK, so hold on line a second and we’re going to see if there’s any additional information that we may need.”

“All right, Kelly, thank you.”

“OK, so I’m going to hang up with you. If you want to leave your phone off, if that makes you feel better, definitely do that option. Call us if anything changes with her.”

“I will call you at exactly 6:30.”

“At exactly 6:30?”

“Yeah, at exactly 6:30.”

“And like I said you can always call 911, and they’ll transfer it over.”

“OK, thanks so much. Thanks, Kelly.”

But Harold Henthorn didn’t wait until 6:30. At ten after 6, he called 911 again, his voice more frantic.

“Respiration is really getting shallow,” he said.

“Did you do CPR?” asked the operator.

“I haven’t started.”

“But they’re getting shallower?”

“What do you recommend?” Harold sounded a little out of breath. “She had no respirations.”

“I’m not quite sure,” said the operator. “I’m going to check with somebody else on that. Were you waving at all? We have a ranger that’s parked on a road that he thinks he may have visibility of someone. He wanted to make sure it’s you. Can you see a vehicle with lights on?

“Yes, I can. Yes, absolutely.”

“Were you waving at him?”

Again, he didn’t answer. Instead, he said, “Let me give you a compass heading on that. Hang on a second. I’ve got a light on looking for a compass. It’s a very small light. I’ve got it.”

Harold was breathing heavily. The operator told him to relax.

“I’m just looking for the compass headings,” he said. “It’s hard to get level.” He said he was 10 to 15 degrees off of magnetic north. “I have started a small fire in a completely enclosed rock enclosure with wet moss on it thinking he can see the smoke.”

“Sir, there might be some climbers in your area. Are you sitting right on the edge looking over a 150-foot fall line?”

“Probably.”

“Can you hold for a moment, I have another emergency call, OK?”

She put Harold on hold. “Dispatch, this is Kelly, what’s your emergency,” she said, answering the other call.

A man came on the line. “Hi, Kelly, this is just a concern from one of our tour guides, people getting too close to the elk in upper Sheep Lakes. They got out there too close and kind of ended up driving them—.”

“I’m sorry, sir,” she interrupted, “we have an emergency going on, but I’ll let them know.”

Another call came in from a ranger responding to a car that wouldn’t start. She disposed of that and said, “Harold, are you still there?”

He said, “You said you have climbers in my area?”

The operator said a ranger was trying to find him. “He’s seeing other people. He wants to make sure which one you were. He’s trying to get that down. Looks like there’s people above you and people below you.”

“Shoot, this phone is cutting out.”

“Sir?”

But Harold had disconnected. He called back and got another dispatcher, the one named Elizabeth. He told her, too, he’d started a fire. “Did they see smoke?”

“Did you light something?” asked Elizabeth, not privy to the previous conversation. A fire in the park after a long dry summer could provide yet-another complication.

“I’m burning moss,” he said.

In between speaking with the dispatcher, Harold reached out to somebody else via text message.

“Barry … Urgent … Toni is injured … in estes park … Fall from rock. Critical … requested flight for life. Emt rangers on way. Please come to Denver next flight. Low cell batt. Please return message.”

Barry Bertolet was Toni Henthorn’s brother. He was also a cardiologist in Mississippi.

When Barry didn’t immediately respond to the text, Harold left a voicemail message: “Check your phone. I have a low cell battery and can’t talk.”

Barry responded with a text asking Harold if he needed help. Harold replied with “H,” which Barry took to mean that he did need help with a capital H.

Barry then called the National Park Service dispatchers while more texts poured in from Harold. One of them came at 8:25 P.M. Eastern Time—which meant it was sent at 6:25 P.M. Denver Time—and read: “Pulse 60 Resp 5.”

“What is status?” Barry texted to Harold at 6:39 P.M. Denver time.

“No min pulse,” Harold ominously replied.

Barry’s fears deepened when Harold texted at 7:12 P.M.: “CPR critt.”

“Is ranger there?” Barry texted back.

“No,” texted Harold.

At about 7:30 P.M. Harold texted, “Can’t find pulse.”

“Maybe still there,” Barry texted of her pulse. “Keep on with CPR.”

“Y,” replied Harold.

At 7:55 P.M., Harold texted Barry: “Cpr … Help 10 min out.”

* * *

Back at the dispatch center, the phone lines were lighting up. While Elizabeth talked to Harold, Kelly reached out on another line to another unidentified law-enforcement official, a man, who sounded like a supervisor, seeking help for Harold.

“Going crazy over here,” said Kelly. “We have a rescue; a woman took a forty-foot fall on Deer Mountain. She’s unconscious but breathing. He’s starting to ask questions like when to start CPR, and I didn’t know how to answer him.”

“She’s breathing, she’s just unconscious, right?” the man asked.

“Respiration is slowing.”

“Shit,” he said. He suggested having Harold call 911 again and connecting him to a police officer who could run Harold through “the protocol”—the series of chest compressions and blowing into a patients’ mouth to try to revive her.

Kelly repeated how busy it was in the operations center. “It’s all backed up, just so you know,” she said—and asked if he could come in and help. He said something about needing childcare and would do the best he could.

It took a few minutes, but somebody knowledgeable in CPR at the Estes Park Police Department was tracked down and given Harold’s phone number. Harold’s phone lit up and he answered.

“Hi, is this Harold? This is Julia from the Estes Park Police Department. They tell me you need some assistance doing CPR.”

“Any help you could give me,” Harold said.

Julia asked about the injured woman. “Is she awake?”

“No, unconscious.”

“I’m going through my questions really fast with you. Is she breathing?”

“Her breathing has gone from ten to five to nothing, to zero.”

Things were buzzing down in Estes Park, too, and Julia urged Harold to have patience. “I’ve got an officer who’s going to help me answer the other line so I can work with you directly,” she said. “What we’re going to do—let me let my officer through the door here, hang on—Is anybody else there with you?”

“No, just me.”

“What we’re going to do is, we’re going to start some compressions. What have you been doing so far?”

“Compressions. Compressions and stop.”

“When you do your compressions, I want you to press down firmly, two inches, with only the heel of your lower hand touching the chest.”

“I’m doing that, yes.”

“I want you to pump the chest hard and fast thirty times at least twice per second.”

“I did that.”

“Let the chest come up all the way up between pumps and tell me when you’re done with that.”

After a couple of seconds, he said, “OK.”

“I want you to check her mouth for an object and remove anything that you may find, if she has anything in her mouth.”

“She has no object in mouth.”

“With your hand under her neck, pinch her nose closed, tilt her head back again, give two more regular breaths and then pump thirty more times.”

“That’s exactly what I’ve been doing.”

“Just keep on doing that routine and make sure you’re doing at least twice per second. Make sure the heel of your hand is on the breastbone in the center of her chest right between her nipples. Have you removed any outer clothing so you can tell exactly where you need to be?”

“Yes, yes.”

“That’s definitely what we want to do,” said Julia. After a few seconds, she asked, “And tell me when you start with the two breaths.”

“You’re telling me exactly what I’ve been doing,” said Harold.

“What I’m going to do now is I’m going to count for you as you go through the breaths. I’ve got my computer on and I can count so we can make sure we’re getting that blood flow.”

But Harold didn’t do that. He spoke over her, saying something about his “cell battery” and that “I’ve got to turn off.”

Exasperation in her voice, the dispatcher said, “Okay, call 911 any time and you’ll get me. Keep on checking her mouth.”

“Thank you, do you know the ETA of the rangers?”

“No,” she said brusquely.

“Could somebody find that out and text that to me, please?”

“I will, definitely,” she said.

* * *

It was now 7:30 P.M., darkness enveloping Rocky Mountain National Park, temperatures plunging into the 40s. It had been more than an hour and a half since Harold Henthorn had initially called 911. He dialed the dispatch center directly and got operator Kelly again.

“You guys have an ETA on the rangers?” asked Harold.

“We actually have a ranger in the area,” she said. “If you can start using your whistle, he’s trying to find you.”

“OK, great, thanks a lot. OK, bye.”

After a couple of minutes, Harold called the dispatch center again.

“It’s Harold.”

“Oh, hi, Harold.” It was another operator, this one a man named Chris.

“You guys have my location yet?” Harold asked.

“We think Ranger Faherty is close,” said Chris. “He gave the other rangers his coordinates, and they’re trying to figure out how close he is to you. He’s been yelling for you. Do you hear him at all?”

“If he tells you where he is, I can direct him exactly to me,” said Harold.

“I don’t think he knows exactly where he is in the dark now. He was just reading his coordinates off of a GPS. Do you have your specific GPS coordinates?”

“No,” said Harold. He said he had gotten his coordinates off a map.

In the background, the dispatcher could be heard talking on the radio to the rescue ranger, who was trudging through the darkness with a heavy pack full of medical equipment somewhere near Harold.

Faherty could be heard asking the dispatcher, “He’s in the valley between the rock outcroppings?”

“You know where that is?” the operator asked Faherty.

“Yeah, makes total sense,” said the ranger. “I didn’t see him in there, I scanned that.”

About a half hour later, Harold called the dispatcher one last time. It was 8:01 P.M., and the ranger was just a few feet away, carefully going down the steep slope toward Harold.

Within minutes, he was there.

Guided by the light of a small fire, U.S. Park Service Ranger Mark Faherty found Harold Henthorn at the base of a cliff. From the moment Faherty arrived, it was a scene unlike anything he’d encountered before. The first thing Harold did when the ranger emerged from the woods was go over to the woman, who was lying on her back on the hard ground, her head wrapped in some kind of cloth, and start pushing down on her chest.

Faherty told Harold to stop, saying he’d handle it now.

The woman appeared to be of middle age and dressed for a day hike in blue jeans, pink shirt, brown boots over gray socks. Blood soaked her light red hair from what appeared to be a severe head wound. She didn’t move.

Faherty checked her vital signs. Her pupils were fixed, she had no pulse and she wasn’t breathing.

At 8:12 P.M., Faherty called the Rocky Mountain National Park’s Incident Command Post to report that Toni Henthorn was dead.

***

Copyright © 2017 Michael Fleeman.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Michael Fleeman is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer and editor and the author of several true-crime books published by St. Martin's Press, including the New York Times bestseller The Stranger in My Bed and Crazy for You about the Andrea Sneiderman murder case in Atlanta. Fleeman will be appearing in the second season of Investigation Discovery's Tabloid, a series about sensational true-crime stories.