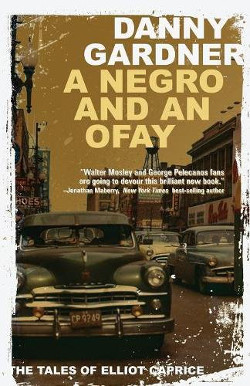

A Negro and an Ofay by Danny Gardner is the 1st book in The Tales of Elliot Caprice series.

A Negro and an Ofay by Danny Gardner is the 1st book in The Tales of Elliot Caprice series.

On the surface, A Negro and an Ofay is a crime novel. Underneath, Danny Gardner’s book is about family—the one you have and the one you make. It’s about going home again and making amends. It’s about learning who you are after a long search.

Elliot Caprice has been to college, been to war, been a Chicago cop, and been on the run. By the time we catch up to him, he’s run out of places to run, and he’s contemplating what happens next. This leads him into a case involving the missing driver of a recently rich woman.

Tangled in the question of whether or not Caprice can succeed at finding his man is whether he’ll be able to save his uncle’s farm from foreclosure, something that nags at him the way only family guilt can. Find the man, get the money, save the farm seems like an easy enough equation, until he discovers he’s not the only one looking for the chauffer—and that the others are willing to kill to find him.

Of course, before he can do any of that, Caprice needs to get himself out of jail.

“You are in the custody of the St. Louis County Sheriff. You’ll be detained until you can appear before a judge. Got it, smart guy?” Fatty said, just before he kicked Elliot in the ribs.

Elliot rose to his feet. Skinny pushed him down the stairs.

“Why am I here when I vaguely remember bein’ dry-gulched in Belleville?”

“You had a police issue thirty-two on your person,” Skinny said. He produced a key ring. “Get comfortable. Make friends.”

He shuddered as the cell door slammed behind him. It sounded eerily similar to the lid of his M18 Hellcat. The blast of body heat combined with the cold limestone felt just like ol’ Lucille’s air-cooled engine exhaust. He was rudely reminded of the involuntary smells men create when their glands respond to despair; sweat and filth, rushed through the air on panicked breaths. Elliot immediately turned back toward his jailers.

“Look here, constable. How’s about my phone call?”

“No calls on Sunday. Gotta wait until morning. Could be in front of the judge by then,” said Skinny.

“That’d be too bad for you, halfie. Beatty is a hangin’ judge,” said Fatty.

“I’m colored. They’re all hangin’ judges.”

There’s a theme in storytelling of turning to home or the people one grew up with when all other options fail, and that’s what Caprice finds himself doing. His childhood friend is a pastor turned sheriff. His former employer has fallen out of favor but not forgotten about him. And the town itself remembers him as a trouble maker and trouble finder but still welcomes him back in their own ways because he’s one of them.

He took his coffee as he had on the job: black and strong. He used it to chase down two hard-boiled eggs plus toast. It took him all of ten minutes to eat without pleasure. A cop’s breakfast. Just enough to keep him on his toes. He laid down a dollar, the tip equal to the bill. Once fed, his brain bathed in caffeine, Elliot was prepared to get himself a haircut and a shave, some duds to show up to his meeting looking professional, and to claim the wheels Izzy gifted him from the yard. It was the colored man’s post-prison trifecta.

… After a straight razor shave, Elliot felt, if not like a new man, at least a clean one. He tried to pay but Boots would have none of it.

“Welcome back, baby boy.”

Caprice balances between worlds and tends to feel out of place a lot of the time because of it. Light-skinned, he hates “passing” because his experience has been that strangers always eventually see him for who he is to them. Caprice would have no difficulty believing that sixty years later people would judge the President by his darkest relative even with the segregation dining areas and water fountains gone. He often “outs” himself and seems disgusted by the hypocrisy and imagined supremacy, but he also has little patience for his “folks” playing games for crumbs because he knows firsthand they’ll be the first to get screwed in the end.

In other words, Caprice is a complicated, complex character who has his own code constructed from his experiences. He’s not necessarily proud of the things he’s done, but he’s not down for wallowing either, and he’s willing to learn and grow.

Specifically, he’s willing to finally let other people in. He’s willing to lean on people who have had his back in the past and people he once protected. Sometimes maturing requires learning we can’t do it all by ourselves, and for Caprice, he spends a lot of the book fighting against this notion.

George’s voice was resolved. “This sin chain linked all the way to my little town. I’m going.”

“I go where George goes.” Ned Reilly walked in through the back door.

“Ned, I don’t think—”

“Save it. If he’s goin’, make room for me.”

Before Elliot could get another word in, the front door opened. In walked Frank Fuquay followed by none other than Amos Doyle.

…

That’s how two and one-half Negroes and two and one-half ofays conspired to bring the FBI to the doorstep of a syndicate associate bearing a grudge.

A Negro and an Ofay is a great book, and the gangsters and crooked authorities in mid-century Chicago make for a fun plot. But the core of this book is its heart.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Neliza Drew lives in South Florida with her husband and too many cats. When not writing, she teaches kids how to punch each other. Her debut novel, All the Bridges Burning, has been called “a triumph.” She can be found online at nelizadrew.com and on Twitter and Instagram as @nelizadrew.

Russia confirmed it had withdrawn from the key towns of Izyum and Kupiansk on Saturday, saying that the retreat would allow its troops to “regroup”.