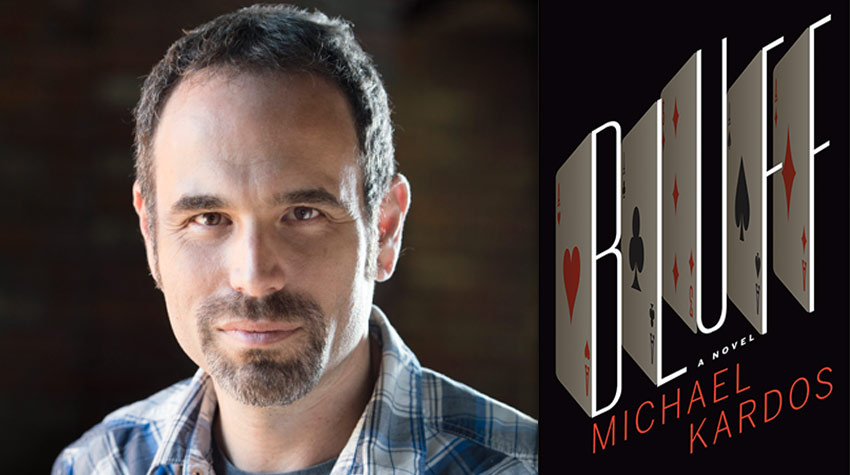

Q&A with Michael Kardos, Author of Bluff

Michael Kardos is the Pushcart Prize-winning author of the novels The Three-Day Affair and Before He Finds Her, as well as the story collection One Last Good Time. He also wrote the textbook The Art and Craft of Fiction. A native of New Jersey, Kardos now lives with his wife and family in Starkville, Mississippi, where he is the co-chair of the Creative Writing program at Mississippi State University. His newest, Bluff, received a starred review from Library Journal; further, Megan Abbott noted: “As lithe and cunning as its characters, Michael Kardos’s Bluff is a masterly exercise in narrative sleight of hand. This is suspense in its purest form—character-driven, immersive and hopelessly addictive. Prepare to be taken.”

Recently, the author kindly conjured up responses to curiosities pertaining to modern magic and its translation to the page, originating an atypical protagonist, crafting sustained suspense, the transferable sensitivity between arts, and the dual importance of discipline and instruction in writing.

What inspired you to write Bluff, and how did you go about researching the topic of modern magic and then translating it to the page?

I was a teenage magician. Not a great one, but not bad. Mostly, I got by on patter and enthusiasm. Anyway, there certainly are parallels between magic and storytelling—from the goal of creating a sense of wonder to the question of how and when to reveal information … these are matters I’ve been thinking about for a long time. I lucked into some of my research: in grad school, I was fortunate to have a magician as one of my students. At 21, he was already touring internationally. This was maybe 15 years ago, but we stayed in touch over the years, and he was a big help when I had questions about sleight of hand as well as the milieu of professional magic.

Poker plays a big role in the novel, too, so I reached out to lots of players at different levels: professional, serious amateur, people who played in casinos, in home games, and online. As far as translating the actual technical bits onto the page … well, the truth is, I cheated at one point by including an illustration of a poker hand.

Your protagonist, Natalie Webb, was shunned after having a liaison with an older magician. In what ways are her circumstances reflective of the real-world double standards that women often suffer, and how does her reentry exemplify the risks and payoffs of the redemptive journey?

The worlds of professional magic and poker are comprised primarily of men. Women aren’t always made to feel welcome by their male peers, and audiences often have certain expectations about the “type” of woman who engages in these activities—everything from what they wear to how they carry themselves. All this, of course, is lousy in life but prime fodder for fiction. An enterprising female magician/cardsharp, it occurred to me, could turn an audience’s predictable expectations into an advantage.

Building suspense is the writer’s equivalent to a magic trick. Can you talk about your process and how the idea of the sleight of hand can be applied to misdirecting readers?

Yes, absolutely! This continues to intrigue me: how a work about magic can take the form of magic. Originally, I even wanted the book itself—the physical object—to somehow be a magic trick. (My editor’s response was something like, “Yeah. No.”) My process with this novel wasn’t so different from the way I usually write: partly planned, partly spontaneous, lots of rewriting to make the voice more authentic. The ending of a novel should feel both surprising and inevitable. And isn’t that true with a magic trick? In essence, all novels—and certainly all suspense novels—contain the bones of a magic trick. It’s just that, in this instance, the parallel is perhaps more evident because of the book’s subject matter.

You’ve been a drummer. Have you found that these seemingly disparate professions have commonalities? If so, what are the similarities to the rhythms of music and writing?

I don’t know if it’s the rhythm, exactly, that is similar, though I suppose a sensitive ear is important for both activities. It’s more, I think, that becoming a drummer taught me the value of doing something steadily for a long time in order to get incrementally better at it. (That, and drumming got me accustomed to rejection and playing to small rooms.)

You are an associate professor of English and codirect the creative writing program at Mississippi State University. In your opinion, what of craft can be taught versus what is intrinsic, and how does discipline factor into the equation?

No one ever asks, “Can violin really be taught?” Yet we hear this all the time with writing. That’s because writing involves the same medium everyone uses—language—whereas a musical instrument has a mode of expression that isn’t what everyone happens to do all day long.

Of course, one’s intrinsic musical proclivity does matter. We can’t all become Itzhak Perlman, even with years of lessons. The thing is, though, you don’t need to become Itzhak Perlman to play the violin well, and neither must you have the intrinsic talent of a Nobel laureate to write some good fiction. Discipline matters a lot, and so does instruction—because discipline can be of limited use and can even be counter-productive if all you’re doing is cementing bad habits.

The bottom line is that some of my students blow me away immediately, and others less so, but there’s no way for me to predict who will ultimately go farthest with their writing. That’s really up to them, the work they put in, their determination and life circumstances, and some luck. So as a teacher, I try to bet on them all.

Leave us with a teaser: What comes next?

With the caveat that it can all change on a dime, I’m currently at the early stages of a novel about the world’s largest art museum heist.

Comments are closed.

Thnaks for Shaering it