Bonnie and Clyde (1967) might be the most well-known movie about an outlaw couple, and Gun Crazy (1950) might be the best. But the title that many credit as the original gangster couple film was made before either of those.

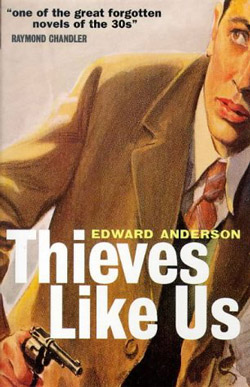

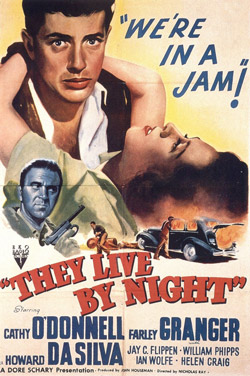

Critically revered auteur Nicholas Ray made his directorial debut with 1948’s They Live by Night, the plot of which largely revolves around an escaped convict and the woman who becomes his lover and traveling companion. Ray’s film was based on a gritty 1937 novel called Thieves Like Us, which was written by Edward Anderson. Anderson was little known in his time and is still under-recognized today. Criterion Collection’s new edition of They Live by Night is a prompt for a fresh look at both the film and novel.

What’s striking about Anderson (1905-69) is that he authored this excellent book—which reads like a mashup of John Steinbeck, Dashiell Hammett, John Fante, and Jim Thompson—yet only had one other novel published in his lifetime. Born and raised between Texas and Oklahoma, Anderson often worked as a journalist and was also a professional boxer and musician. For one stretch, he led the life of a train-hopping hobo. He also made an unsuccessful attempt to work as a screenwriter in Hollywood. With Thieves Like Us, the second of his two novels, he created not just a classic story of a fugitive and his lady accomplice but a memorable tale of Depression-era desperation.

In Anderson’s book—which is set in his home territory of Oklahoma and Texas and is told in a lean, hard way that will win favor from noir fiction enthusiasts—the story opens with the exploits of a trio of men who have escaped from prison together. All were serving life sentences. The cons survive by becoming traveling bandits who rob banks in various towns and then hide out between heists.

In Anderson’s book—which is set in his home territory of Oklahoma and Texas and is told in a lean, hard way that will win favor from noir fiction enthusiasts—the story opens with the exploits of a trio of men who have escaped from prison together. All were serving life sentences. The cons survive by becoming traveling bandits who rob banks in various towns and then hide out between heists.

Eventually, the tale comes to focus on one of the three: Bowie Bowers, 27, who was jailed for the fatal shooting of a shopkeeper during a holdup that occurred when he was 18. Along the way, Bowie becomes romantically involved with Keechie, a no-nonsense, wise-beyond-her-years young woman who is the daughter of a man who aids Bowie and his criminal buddies in their post-jailbreak endeavors. Much of the novel’s tension comes via the dilemma faced by Bowie, who gets torn between his lover and his criminal brethren; Keechie doesn’t mind that her man is a killer and a fugitive, but she wants him to make a life with her and to stay away from the men with whom he fled from prison.

Throughout, the novel is sympathetic to Bowie and his two accomplices, who go by the names T-Dub and Chicamaw. The men have a code of honor by which they live, one that is separate from the normal behavior system of common, law-abiding folk. The way Bowie and his pals see it, the kinds of people who own banks and otherwise take financial advantage of the common man are “thieves like us,” just ones who rip people off legally. The outlaws don’t mind taking money that belongs to those kinds of citizens, and they have no love for the cops who help maintain the system whereby this kind of accepted thievery can take place. But when they encounter somebody they consider “real people,” they will respect such a person and do them no harm. I don’t know if Woody Guthrie ever read this novel, but if he did, I feel assured he would have appreciated its sentiments.

Ray, who later directed acclaimed titles such as In a Lonely Place (1950), Johnny Guitar (1954), and Rebel Without a Cause (1955), began his career powerfully with They Live by Night. With the help of Charles Schnee, Ray wrote the screenplay adaptation of Anderson’s novel. John Houseman—known mostly for his role on the 1970s TV show The Paper Chase but whom film bluffs mostly think of as a collaborator of Orson Welles’s—introduced Ray to Anderson’s novel, and Houseman became producer of the film.

The movie was a long time in the making and releasing. RKO bought the rights to Thieves Like Us as far back as 1941, and Ray’s film was completed two years before the studio finally got around to getting it in theaters. Anderson received a paltry one-time fee of $500 for the film rights. Robert Altman remade the movie in 1973, with a title to match the book’s, four years after Anderson’s death.

The movie was a long time in the making and releasing. RKO bought the rights to Thieves Like Us as far back as 1941, and Ray’s film was completed two years before the studio finally got around to getting it in theaters. Anderson received a paltry one-time fee of $500 for the film rights. Robert Altman remade the movie in 1973, with a title to match the book’s, four years after Anderson’s death.

Plot-wise, there are some differences between Thieves Like Us and They Live by Night, but the deviations Ray made from the details of Anderson’s story are relatively minor and not worth elaborating on here. The biggest thing that separates the two versions of the saga is that Ray imbued Anderson’s starkly realistic tale with a romantic aura. In the book, you know that Bowie cares for Keechie and that she is emotionally dedicated to him, but their love affair is written about in a measured, day-to-day, often bleak way there. For the big screen, Ray made their amorous connection more sweeping and heart-rending. And he added a dramatic, tragic touch to their seemingly doomed relations.

In terms of quality, it doesn’t seem worth questioning whether the book is better than the film or the way other way around. Both are excellent. Some admirers of the novel might take exception to the melodrama with which Ray infused the story, while others will see those strokes as effective and necessary for the big screen.

Personally, I’m not completely sold on Farley Granger, who plays Bowie in the cinematic version and whom Ray wanted for the role after observing Granger at a party. But then, there’s just something about Granger’s screen presence that always bugs me, despite the fact that he has key parts in several movies that I treasure, including Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) and Strangers on a Train (1951), as well as the giallo classic Amuck! (1972).

Check out Brian's 10 Essential Giallo Films!

Cathie O’Donnell is excellent as Keechie in the movie, and all the more so because she’s on the plain jane side—not at all a glamorous leading lady—which is right for this story and her role. Howard Da Silva also excels as the creepy, one-eyed Chicamaw—a role for which Robert Mitchum was considered.

Fans of They Live by Night, and of Ray’s film work in general, will appreciate Criterion’s usual bounty of bonus features on the disc and its booklet.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and reviews and articles of/on books, music, and film. His work has appeared in 25+ publications since 2008. His pieces on crime fiction have also been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Paperback Parade, The Life Sentence, Stark House Press, and Mulholland Books. Brian lives in Durham, North Carolina.

His writing blog can be found at: http://briangreenewriter.blogspot.com. Follow Brian on Twitter @greenes_circles

“But the fundamental right to protest remains as a keystone of our democracy.”