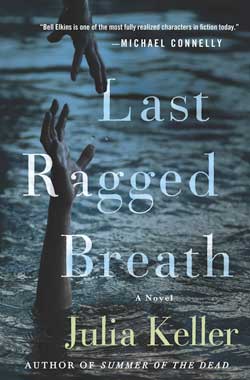

Last Ragged Breath by Julia Keller is the 4th mystery in the West Virginia Prosecutor Bell Elkins series (available August 25, 2015).

Last Ragged Breath by Julia Keller is the 4th mystery in the West Virginia Prosecutor Bell Elkins series (available August 25, 2015).

Royce Dillard doesn't remember much about the day his parents-and one hundred and twenty-three other souls-died in the 1972 Buffalo Creek disaster. He was only two years old when he was ripped from his mother's arms. But now Dillard, who lives off the grid with only a passel of dogs for company, is fighting for his life one more time: He's on trial for murder

Royce's future lies in the hands of Prosecutor Bell Elkins. Will she overcome her toughest case yet?

Chapter One

Goldie was a six-year-old shepherd-retriever mix with a thick yellow coat that had inspired her name, a riotous tail, and chocolate-brown eyes that suggested profound depths of mysterious wisdom. At present that wisdom had coalesced into a conviction that something smelled mighty good—that is, powerful and unusual—somewhere along the slanting bank of Old Man’s Creek. Wet black nose plowing a shallow trench across the rugged terrain, body balanced expertly to accommodate the steep grade, Goldie rammed forward along the upper brow of the creek bank, sniffing and quivering. The smell, as it intensified, became even more intoxicating. It was like a string pulling her along, winding itself tight on a bobbin at the other end. Everything else dropped out of Goldie’s thoughts.

From behind her came the distant syllables of someone calling her name: “Goldie! Here, girl! Go-o-oldeee! Come on!”

She didn’t hear it. Rather, she heard it, but the hearing part and the subsequent ignoring part constituted a single supple action that had nothing to do with volition, nothing to do with stubbornness or calculation. Goldie wasn’t being disobedient. Goldie was being a dog.

“Go-o-o-ldee! Come on!”

She didn’t even lift her head. She knew her name, and she had a definite affection for the man yelling it, but those two facts counted for nothing now. She was All Nose. Her nose was her destiny.

“Goldie, you ornery girl, you. Taking off like that. Leadin’ me a merry chase. Never seen the like.” The yell had subsided into a running grumble. Andy Stegner was getting closer, following the trail of mashed-down dirt and still-trembling branches that testified to Goldie’s hasty journey past them.

He was, at the moment, sorely regretting the fact that he’d stopped to pick her up that morning. Goldie was turning out to be Trouble-with-a-capital-T. His neighbor, Royce Dillard, had seven dogs, including Goldie. That was down from the fifteen he’d had a year ago, which sounded like the aftermath of a massacre but was actually due to the fact that eight of the dogs were dreadfully sick when Royce first took them in, and it was only through Royce’s kindly labors that they’d lasted as long as they did, and were granted, one by one, a serene, dignified death. Stegner couldn’t keep a dog—his wife was allergic to the fur, her only fault as far as he was concerned—but he liked to have company when he checked his raccoon traps. Royce never minded lending one out for a morning’s patrol.

Today, though, Goldie was climbing Andy’s last nerve. The instant they ventured near the creek bank she’d taken off as if she had firecrackers tied to her tail. She seemed determined to ignore him. It wasn’t like Goldie to act this way; she was a good dog. Something had gotten hold of her and wouldn’t let her go, just as surely as Andy’s traps captured skinny gray-black raccoons from October to February, the official trapping season allowed by state law.

Goldie plunged forward, whipping back and forth between the leafless trees. She crossed the dirt and the rocks and the low scrubby bushes and the scat and the sloughed-off hunks of bark and the burrs and the seed pods and the dead insects and the dented green Mountain Dew cans. All emitted excellent smells, smells that under normal circumstances would have caused her to pause and savor—but the smell drawing her forward asserted its dominance. It separated itself from the others. It was the King of Smells. It ratcheted up in deliciousness a few notches more, even after it seemed that it couldn’t get any more wonderful.

Goldie was getting close.

“I mean it, you rascal! You get back here! Goldie, come on!”

He was wasting his breath. The dog had it in sight now, mired down there in the creek itself, a broad hump of brown. It was snagged between a rock and a batch of cattails that, wind-whipped and top-heavy, arched low over the greenish-silvery water like skeletal fingers reaching into a fingerbowl. Goldie’s hearty bark startled two turkey vultures, newly returned from their winter journey south, in mid-feast. They rose quickly and corkscrewed away, broad wingspans catching the circular updraft of air currents. They would be back. They had infinite patience.

Goldie slid deliriously down the bank—not even trying anymore to maintain her balance, enjoying the free fall of four scrambling paws and a glorious sense of anticipation—and collided with the hump. The smell exploded in her nostrils. She uttered a brief yip of joy.

She was up to her belly in the frigid water, water that had recently made its late-winter pilgrimage down from the mountain to creeks like this one, and she was thrashing and nipping at the hump, trying to unravel the core source of its splendid stink. She didn’t mind the cold one bit. She pulled at a section of the brown mass. There was a quick sound of ripping cloth as something came away in her teeth—but it tasted bland, and she spat it out, flapping her tongue to rid herself of the unimportant. A few brown threads dangled from her left incisor as she returned to the mysterious mound. She moved to the other side of it, parting the water with her wide golden chest, prodding the object repeatedly with her muzzle.

“There you are, you ornery dog, you!”

Andy looked down at her from the top of the bank, hands at his sides, breathing hard. The left sleeve of his denim jacket was torn and his ball cap had been knocked askew. Low-hanging branches had done the damage. A few years ago he might’ve been able to keep up with her when she broke loose that way, running a good half mile like a furry streak of lightning. But he was sixty-one years old now. And creaky as hell. Arthritis pinched at his joints as if somebody—a mean somebody—had taken a pair of pliers to them.

“Whadda you got there, Goldie?”

He descended the bank carefully, gingerly, heel-hard, keeping his body sideways so that he wouldn’t go headlong if he stumbled, grabbing at the thin branches of spindly trees and then releasing them again after he’d descended further. Goldie had gone for the water at another angle, but he went this way because there seemed to be a bit of a path here already, two faint parallel lanes of pushed-down plants, a running indentation. Then a branch snapped back and whacked him in the face—Dang, he exclaimed—and he broke it off and kept going.

Down below, Goldie splashed around like a young pup. Her tail was going in wild, incessant circles. She was obsessed with whatever it was that slumped by the creek, half-in and half-out, nudging it with her nose, then backing off and barking. Her barks rang sharply in the frigid air of the mountain valley.

“What’s got into you, girl?” Andy muttered as he neared the spot where the dog pranced and bounced and shimmied. Her glee was giving way to agitation. The strong smell was still pleasurable but also perplexing, and Goldie seemed eager for him to help her solve it.

Moving closer, he saw that the hump was covered by a big brown coat. He picked up a wrist-thick black branch at water’s edge. Used it to poke at the object. A few more pokes would be required to dislodge the thing. He pushed at the far end and something broke off, swaying briefly until it spun onto its other side, like a bobbing beach ball. He leaned toward the broken-off piece, holding the stick in both hands now so that he could hook it. He drew it closer to the bank.

Goldie instantly backed off, setting up a hysterical barking. Andy felt his stomach drop. Rational thought fled from his mind. Vomit rose in his throat.

It was a human head. Andy was staring at the place where the face ought to be. He knew a face belonged there because of the gray ear-shaped objects on either side of the central cavity and because of the presence of matted hair at one end. At the other end was the ragged fringe of what Andy now realized was a severed neck. The soft chasm in the center—where you would expect to see eyes and nose and mouth—was scooped out, replaced by a wormy mess.

Goldie, sensing his shock, not sure what she ought to do about it, went from barking to a kind of eerie, sirenlike crooning, an ancient song of lament that was as mindlessly instinctive to her as was her earlier devotion to the voluptuous smell of death.

Chapter Two

The Highway Haven truck stop occupied six and a half acres of asphalt at Exit 127 along the major route linking Acker’s Gap, West Virginia, with points east and west. It was divided into two distinct halves, with six rows of pumps—two pumps per row—on either side. One side was marked TRUCKS ONLY. The other was designated ALL OTHER VEHICLES. On the trucks-only side, the lanes between the pumps were wider, allowing the drivers of the eighteen-wheelers to maneuver with relative ease as they lined up their famished vehicles for lengthy refills. The heavy odor of diesel fuel was like a truth you couldn’t turn away from.

Belfa Elkins parked her Explorer in front of the glass-walled building, a combination snack bar, coffee shop, convenience store, video-game arcade, lavatory, and, for truckers, shower facility. The building divided the truckers’ side from the other side. She had made the drive here from Acker’s Gap in a surprisingly quick fifteen minutes, but knew better than to chalk it up to skill or even luck: There was always a lull between 5 and 6 A.M. on this stretch of interstate, and the clock on her dash told her it was just before 6. Later this morning the place would be packed, crammed with buglike compacts and massive RVs and only slightly less massive SUVs that had turned off the highway and swung hungrily toward the pumps, along with all the big rigs driven by the professionals, the men and the very few women who could handle an eighty-foot length of steel and chrome and momentum—a vehicle that weighed forty tons even before its load was factored in—with apparent ease. After fuel, the next most-desired items for travelers were bathrooms and food, and so most of the drivers of the regular vehicles, after they’d finished their business at the pumps, nosed their cars into parking spots in front of the store. If it were any later in the day, there would’ve been no open slots left; Bell would have been forced to use the spillover lot in the back.

She was an attractive woman with a slender build, medium-length wavy brown hair, and a quiet intensity in her gray eyes. Those eyes seemed to take in everything all at once, filing most of it away for later; there was nothing cursory or slack about her gaze, nothing casual. She was closer to forty-four years old than she was to forty-three, but she looked younger than that, owing in part to an edgy restlessness, a sort of spirited impatience, in her manner. She wore jeans, a taupe barn coat with a dark brown collar, and a blue cable-knit sweater. The thin strap of a black leather purse made a diagonal slash across the front of that sweater.

Just before she opened the double doors with the giant red H painted on each side of the glass, she glanced to her left. The last parking place on that side was occupied by a white Chrysler LeBaron. Nick’s car. She felt a slight but definite pang. In years past, when she arrived at a crime scene and looked around for his vehicle, her eyes would search automatically for a black Chevy Blazer with an official Raythune County seal on both sides. This wasn’t a crime scene, but she’d automatically had the old expectation. Since November, however, when Nick had handed over the Blazer keys to his successor, he had been driving his own car. He had decided not to stand for reelection. His deputy, Pam Harrison, had won easily.

She gave the car a quick going-over with her glance, same as she’d done the three previous times she’d come out here to see him. The Chrysler didn’t suit him. Nothing suited him but the Blazer.

On the curb in front of his vehicle was a pert warning delivered in red stenciled letters: RESERVED N. F. He had his own spot. Unreasonably, that also bothered her; it gave his new job an aura of permanence, of finality. This wasn’t some temporary gig—which she already knew, of course, but seeing it spelled out that way forced a firmer kind of knowing.

Nick Fogelsong worked here now, as head of security for the Highway Haven chain. He wasn’t coming back to the courthouse.

She and Fogelsong had worked together for six years. She was the prosecutor; he was the sheriff. They had been friends since Bell was ten years old—he was one of the few people she allowed to call her by her given name, Belfa—but it was as colleagues, as professionals, that they had truly bonded. They had solved difficult cases. They had faced death together, more than once. They had sparred and argued. They had gone long days without speaking after especially intense quarrels over tactics or priorities or ethical issues—and then resealed their friendship over long chats while chain-drinking cups of black coffee at JP’s, a diner in Acker’s Gap. They’d run the justice system as best they could in this beautiful, beleaguered patch of West Virginia.

All of that was over now. In the fall, after his testimony at a trial that concluded one of their most challenging cases—the middle-of-the-night murders of two defenseless citizens, and other revelations that had shocked a town whose residents thought they were well beyond that kind of dark astonishment—Nick Fogelsong announced he was giving up the sheriff’s post. He didn’t notify Bell before he did it. He was afraid, he told her later, that she’d talk him out of it. And I would have, too, she’d snapped back at him. You bet your ass I would’ve done just that. She was still upset when she said it, still mourning the loss of him as her comrade.

She’d had an inkling he was losing his enthusiasm, losing his keen edge, losing his relish for the job—but who didn’t, from time to time? Who didn’t occasionally falter, wondering if it was all worth it? This was a place that would challenge anybody’s optimism. It featured, after all, a steady cascade of falling-down shacks and crumbling roads and slow slides into alcoholism and drug addiction, along with red spikes of random violence. To believe in the future around here required a unique kind of fire. You needed your anger, an anger that initially had to be directed at the long line of public officials who, throughout the last century, had sold out the state and its uniquely bounteous natural resources to unscrupulous corporations. An anger that was creative instead of destructive. A vigorous, motivating anger. A righteous anger. Without it, you ran the risk of sinking down into the same sticky pit that had swallowed up the very people you were trying to help.

Fogelsong, though, had given up. That’s how Bell saw it, anyway: He knew as well as she did how much was at stake around here, how much they were needed, and he’d put a Gone Fishin’ sign on the front door of his life. He’d shed his sheriff’s badge and his hope that things could ever change, and he’d walked away.

“Excuse me, ma’am.”

Bell stepped aside, realizing that she was blocking the narrow sidewalk and thus impeding access to the store. Moving past her, a heavy man in a green plaid wool coat pulled at the ragged bill of his Peterbilt cap. “Ma’am,” he repeated.

She followed him in. Rolling off his shoulders was the odor of nonstop tobacco use and truck-cab staleness, a sour, adhesive smell that seemed to be a distillation of everything she was feeling about the day that lay before her.

* * *

The store had few customers at this hour on a Saturday, but still felt crowded on account of all that it stocked: stairstepped wire racks of candy, mini doughnuts, gum, cookies, mints, nuts and sunflower seeds; bright rows of crackling bags of chips and pretzels and popcorn and two-liter plastic bottles of soft drinks; barrels filled with discounted DVDs of John Wayne movies and complete seasons of The Andy Griffith Show; waist-high freezers featuring ice-cream bars and Popsicles. On account of the snapped-in tubes of fluorescent lighting that hummed overhead there was a bright, sunrise feel to the place, an atmosphere bound to eventually surrender its taut freshness over the long course of the day but that had yet to begin that unraveling.

Nick was over at the self-serve coffee section, topping off his chipped gray mug. Bell knew that mug. She’d seen it on the desk in his courthouse office every day—including Saturdays and Sundays, because neither she nor Fogelsong were inclined to take weekends off—for the past half-dozen years, which meant that she’d started her morning with that mug as part of her visual landscape at least two thousand times, give or take.

It didn’t belong here in the Highway Haven, any more than Nick did.

Alerted by the two-note chime that cheerfully did its job each time the glass doors popped open, he looked up and saw her. He waved and tilted his head. She got it, and nodded. He wanted her to meet him in his office at the back of the store. She lifted an imaginary cup to her lips; now it was his turn to nod. She’d be there as soon as she’d fortified herself with some coffee.

His office was located down a linoleum-floored corridor, past the squat red YOUR WEIGHT AND FORTUNE FOR A PENNY machine and the knockoff brand-name cologne dispenser and the locker room and the waiting area for the shower facilities. At peak times, this hall was packed with truckers waiting for their assigned numbers to be called over the public address system; the summons meant it was their turn for a shower.

“Good to see you, Belfa,” Nick said.

“Likewise.”

He edged his way behind the black metal desk, turning sideways to do so. He had a large square head topped by sprinkles of short-cut gray hair and a linebacker’s body—wide shoulders, big hands, but with a certain nimbleness, an essential balance, in his movements. As he sat down, he placed his mug on the blotter so that he could grip both arms of his chair and lean back. Both sides of his suit coat fell open, revealing a snowy expanse of snug-fitting white shirt. Bell noticed the beginnings of a belly on him. Maybe, she thought with a sour little grimace, he ought to spend a penny now and again to keep tabs on that.

The observation was mean and small and unworthy of her, but Bell couldn’t help herself; she was mad at him and she needed to get it on the record, even just in the privacy of her own ruminations. She knew the truth of the old West Virginia aphorism: Hit dogs howl. If you felt like someone had done you wrong, you reacted. You had to. Didn’t you?

The office was small but neatly organized. It had been a mess when Fogelsong first took over: file cabinets askew; monitors linked to the ancient security cameras stacked up every which way, their cords twisted and dangling; dirty cinder-block walls dotted with taped-up notes that constituted a never-ending to-do list. Nick’s wife, Mary Sue, had helped him restore order here over a couple of weekends. The man who’d held the job previously was a retired West Virginia state trooper named Walter Albright; at the company’s insistence, he had agreed to give it up after seventeen years. Nick couldn’t figure out how Albright had gotten anything done—hell, he told Bell, he didn’t know how the man had been able to think straight—amid the frantic, impossible jumble that had seemed to churn around one’s ankles back then, bubbling up like storm water from a backed-up sewer drain in a deluge.

“Cold as all get-out this morning,” Bell said. She took the only other seat in the room, a black metal folding chair facing the desk.

“Thought it might be warmer by now,” he said, by way of agreeing with her. “Never sure if spring’s really coming. Every year about this time, I start to worry. What if it just stays like this? What if somebody somewhere decided that we don’t deserve that pretty spring weather and we get stuck year-round with the cold and the sleet?”

“Know what you mean.” Bell pulled off her jacket and twisted around so that she could hook it over the chair’s rounded back. Seeing Nick Fogelsong in a suit and tie was something she had to get over in stages; she couldn’t assimilate it all at once. His suit was light gray, with a narrow black tie. Even with a couple of extra pounds, he looked good. Dapper, even. Professional. She couldn’t deny it.

But it still wasn’t right for him. He ought to be in a sheriff’s uniform, in the ugly brown polyester pants and shirt, topped off with the broad-brimmed hat and the thin band of gold braid encircling the sweat-darkened crown. There was a part of her that wanted to tell him so right now, to bust through the crust of all the politeness and the nice greetings and the talk of weather—weather!—and to lean forward and say, For Christ’s sake, Nick, stop this nonsense and get back to the courthouse.

To be sure, most people thought Nick Fogelsong’s move a wise one. He was getting older, and this was a sweet deal. Highway Haven’s president had read about his success in a number of cases and made him a generous offer: Fogelsong would oversee security procedures and personnel screening at the company’s eight locations in southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, and he’d still be able to keep his home in Acker’s Gap. The tiny office was only in use when he was visiting this location. His real office—a spacious one, Bell had heard, with a secretary and a wet bar and pictures on the wall, all frills that Sheriff Nick Fogelsong would’ve disdained—was at the chain’s headquarters in Charleston.

Nick pointed toward her Styrofoam cup. It sported a pattern of interlocking red Hs around the white circumference. “Coffee suit you?”

“It’s fine.”

“Good. How’s Carla?”

“Confusing the hell out of me, but otherwise—she’s great.” Bell’s eighteen-year-old daughter lived in Alexandria, Virginia with Bell’s ex-husband, Sam. Carla had graduated from high school the spring before, but decided—just for the time being, she’d said, just for now, adding Really, Mom, I promise—to put off college. Carla had explained that she didn’t know what career she wanted to pursue, and then further explained that it was totally pointless to spend a boatload of money on tuition until she’d made up her mind.

“Kids’re required to drive you crazy at regular intervals,” Nick said. “There’s actually a law on the books to that effect.”

They were quiet for a run of seconds. The catch-up question had been necessary; not only had Bell generally avoided the place since Nick started his new job, but their paths didn’t cross elsewhere, either. She didn’t buy her gas here. The Lester station was closer to Acker’s Gap. Bell didn’t like the crowds that normally thronged the Highway Haven. And there was the other thing, too. There was the fact that driving out this way meant getting just a small, tantalizing taste of what she’d had before on a regular basis, and maybe had taken for granted: Nick Fogelsong’s company and counsel. Sometimes it was better, she thought, to move on. Try to forget.

When she’d called him the night before and requested a meeting today on official business, he said, “Sure, come on by.” She had started to make a counter-proposal—maybe he could head into town and save her a seat at JP’s?—but realized, just in time, that that would be even worse: Sitting across the table from him at the place they’d met almost daily would be borderline unbearable. She preferred to drive out to the interstate and see him here. In new surroundings. In a place where she didn’t have to bump into memories every other second.

“So what can I do for you?” he said.

“Had a briefing from the state police. Wanted to make sure you were aware of what’s going on.” She’d found a paper clip on his desktop and proceeded to take it apart while she talked, twisting and bending it. “Major new distributor of oxy. Need to be on the lookout.” Oxy meant oxycodone, one of the prescription drugs that had drastically increased the crime rate in the area.

Only Nick Fogelsong had ever seemed to understand, in the same visceral way that Bell did, just how prescription drug abuse had gotten a deadly purchase on the region. Recreational drugs, by contrast, were easy to deal with. Pot, cocaine, even methamphetamines—those were familiar blights, the users easy to spot, the dealers bottom-feeding louts whom deputies could scoop up like excrement in a public park. But prescription drugs were different. They were legally supplied, in many cases, by physicians, physicians who either didn’t know—or didn’t care—that the pills were ferociously addictive. After only a few weeks, people who had sought relief for a torqued back or an infected tooth found themselves dependent on the pills, with no way to pay for them—except criminal activity. And by that time, they’d moved on from doctors to dealers.

These were people who never before in their lives would have contemplated an illegal act—but who, when confronted with a clawing, ravening need for the golden ooze of contentment that slid through your gut when you swallowed a pain pill, would do anything to feel that settle-you-down sensation, just one more time. And then one more time after that. Just once more. Swear. They weren’t looking for a way to get high. They were looking for a way to feel okay again.

“Shit,” Fogelsong said, putting as much frustration into a single syllable as it could hold. He and Bell hated the drugs, but they hated, too, the circumstances that sent people hurtling toward them.

By what right could you tell a family from back in the hollows that things would ever get better? That if they worked hard and got an education and avoided traps like alcohol and drugs, they’d be able to find a good job and know a different kind of life? It wasn’t true. The mines were dead. The pay at the shiny fast-food places along the interstate was laughably low, not even close to being enough to live on, much less raise a family on. The real enemy was an invisible one, a force that trapped people even more definitively than the mountains did. It was an attitude, a default setting of defeat. You could always leave; but if you stayed, you faced long odds and, more than likely, a short life.

“So that’s all we know so far,” Bell said. She twisted the paper clip back and forth until it was no longer a paper clip, but a short straight piece of steel. She didn’t have to tell him what he already knew: Truck stops were notoriously common distribution points for the pills—and for the heroin that was, perversely, cheaper than pills and thus had begun an entirely new spiral of addiction in these hills, an auxiliary misery. “The state police are being extra attentive,” she added. “Notifying local law enforcement, prosecutors, school authorities—everyone who understands the drug trade and has a stake in stopping it.”

He fingered his tie gingerly, as if he’d just discovered it was there. “Not a good time for the bad publicity,” he said. “What with the new resort coming, I mean.”

A Virginia-based firm that called itself Mountain Magic had recently purchased a twelve-hundred-acre parcel stretching across portions of Raythune, Collier, and Steppe counties. The plan was to build a resort to rival The Greenbrier, the historic and palatial facility in White Sulphur Springs that had hosted kings, queens, senators, presidents, and CEOs. Because no matter what else was going on with the people of West Virginia—poverty, addiction, despair—the landscape was a thing apart, a separate and unassailable fact. In the spring to come, like all the springs before it, the mountains would rise into a seamless blue sky, the massed interlocking trees on the sides of those mountains would make a solid block of spectacularly vivid green that drifted its way into your dreams, and the brown rivers would move so fast that their supple surfaces resembled the sleek back of a muscular animal in a stretch run.

“Oh, come on.” Bell’s response to his point was sharp and dismissive. “Won’t matter a damn. The billionaires who’re putting up money for that thing don’t care about local crime stats. They hire their own armies. Once the resort’s up and running, the place’ll be crawling with private security.” Too late, she remembered that Nick was now private security himself; her remark could be construed as a dig.

Well, hell. He was a big boy. He could take it.

“Might cut down on their bookings, though,” he said. There was no indication he’d felt insulted. “The negative press, I mean.”

Bell shook her head. “No way. That resort won’t be connected at all with what’s going on locally. The guests’ll come and go and never set foot beyond the tennis court or the golf course or the sauna or whatever the hell else they build.”

“You don’t sound too happy about it.”

She shrugged. “If it means new jobs—good-paying ones—I’ll be over the moon. But there’s been no word yet about how many local people they intend to hire. If they’re going to use our land, the least they can do is put our people to work.” She was getting wound up, despite herself. “This state’s been exploited long enough, don’t you think? We’ve suffered for years from absentee landlords and all of their promises. Maybe it’s time we just told them to go away and leave us alone. Go use up somebody else’s natural resources. These are our mountains. Ought to be our decision about what happens to them.”

Nick created a crooked arch with both sets of fingertips. He waited a few seconds to let some of her anger burn off, and then he said, “It’s progress, Bell. Progress and change.”

“And you think I’m against all that.” She was irritated. What did he take her for—some barefoot granny back in Briney Hollow who still reminisced about the superiority of horse-pulled wagons and outdoor privies?

“No,” he said. “I just think you’re anticipating the extra aggravation that strangers always bring—even strangers who’re investing money in the region. Can’t say you’re wrong about that. I’ve met the company’s marketing guy. Name’s Ed Hackel. Not exactly the shy, retiring type, that’s for sure. Slicker’n goose grease. After he shakes your hand, you feel like you oughta check for your watch and your wallet. But then again—that kind of job, you’ve got to be a hustler.” He let the arch collapse and put his palms flat on the desktop. Scooted his chair in closer. “Heard any timetable yet for breaking ground?”

“They’ve run into a snag.” She watched as the news altered his posture, causing him to sit up straighter. “That marketing guy you mentioned—Hackel—has been calling the county commissioners about twice an hour all month long and raising nine kinds of hell. There’s a thin strip of land on the southern border of the acreage that the company’s already purchased. They’ve got to have it. Provides their best access to the interstate.”

Fogelsong nodded. This was old news. “Belongs to Royce Dillard. They’re giving him a pile of money for it.”

“Yeah. Trouble is, he changed his mind. Doesn’t want to sell.”

“Lord,” he said. “That’s Royce for you.” Dillard was a recluse, a man who lived in rural Raythune County in a cabin he’d built with his own hands, amidst a silence broken only by the barks and howls of a retinue of old dogs—mutts and castoffs, mostly, dogs whose homelessness had destined them, before Dillard’s intervention, for legally sanctioned elimination by an animal control officer. Dillard was only seen in Acker’s Gap every few months or so, when he walked into town pulling an old wagon and bought his supplies. He stopped as well at the post office, where he’d sweep the accumulated mail out of his post office box into a plastic grocery sack.

“It’s not like they’re asking him to give up his home,” Nick mused. “His cabin’s on a little sliver of land over by Old Man’s Creek. They’ve got their eye on a bigger chunk he bought back in the eighties. With the settlement money given to Buffalo Creek survivors. Way I hear it, he’s always planned to open some kind of animal sanctuary on the spot. Dogs, I believe, are about the only living creatures Royce has any use for. The parcel’s just been sitting there, though, all these years.”

“Company’s got to have it. No land—no resort.”

Nick nodded. “Predictable, I guess, that he’s making a fuss. Royce is an odd bird. But he’s got his reasons for being a bit peculiar. Had more than his share of tragedy, that’s for damned sure.” He thought about it. “When he was five, six, seven years old, there’d be a TV crew here every February twenty-sixth, on the anniversary of the flood. Wanting to do an update. Wanting to know how much he remembered about that day. Then it tapered off. Folks forgot.” Nick rubbed his chin. “Don’t imagine Royce ever forgets. Not for a day, maybe not even for an hour.”

Bell stood up. Time to go. She could have handled this errand by phone, and right now, very much wished she’d done so. What did she hope to gain by seeing Nick in person? Their relationship had changed too much, too fast.

Restless, not sure if she ought to shake his hand—they’d never followed social rituals like that before, but things were different now—she fingered the uncoiled paper clip and then used one of the sharp edges to scratch at a spot on the back of her other hand. “I’m sure the whole mess will somehow find its way into a courtroom,” she said. “And at the end of the day, the only people who profit will be the lawyers.”

“Funny way for a lawyer to talk.” He was ribbing her, just like in the old days. “Takes one to know one, huh?”

“I guess.” She wasn’t in the mood. “Getting back to the business at hand—keep an eye out, will you? Hate to see another pill mill get a foothold around here. If you see anything suspicious, give Sheriff Harrison a ring.”

“That’s what I’m here for.” Nick stood up as well, indicating with a sweep of his big hand the monitors stacked neatly along the wall and their shifting stream of gray-and-white images, recording what went on at the cash registers and in the corridor leading to the showers. Another set of monitors displayed the scenes from the area around the pumps and from the perimeter of the store. “Had to update everything. Top to bottom. Damn near every piece of surveillance equipment we have. I can’t quite figure what Walter Albright was thinking—letting it deteriorate the way he did. Half of the security cameras weren’t in working order. Management told me to spend whatever it took to bring us into the twenty-first century. All I needed to hear. By the way,” he said, shifting his tone as he shifted his topic, “I mentioned to Mary Sue that you were coming by. She made me promise to ask you over for dinner tonight. Nothing fancy—probably venison chili—but it’s been way too long. I know it’s short notice and all, but—”

“Can’t. Tell her thanks, though.”

“Okay. Another time.” He waited. Usually Bell would explain a turn-down. But she didn’t, so he had to pry. “Better offer?”

“As a matter of fact, I have a date.”

“Well. Well, now.” His face broke open into a smile. “Do I know the lucky fella?”

“No.”

Once again, he waited for more details. Her expression informed him that none would be forthcoming. The silence lengthened, thickened. Many things occurred to her within that silence, and Bell noted them, one by one: Nick was now on the outside of her life, looking in, and even though she’d acknowledged that leaving the sheriff’s job was his decision, that he had to do what was best for himself and for Mary Sue, she still wasn’t reconciled to the change. She missed him. She knew he missed her, too. But if she acted as if they were still close—if she talked with him about her life, the way she’d always done before—then she would be letting him off the hook too easily. He had abandoned her, dammit. He had to face the consequences of that.

Finally, Nick said, “Guess both of us had better start our day’s work.”

She put the straightened-out paper clip in her pocket and lifted her jacket from the back of the folding chair. Once it was on, she picked up her purse and her coffee cup.

“Hey,” Nick said. She paused at the threshold. “We offer free refills on the coffee,” he said lightly. “Make sure you take advantage. For the drive home.”

Bell didn’t know what she’d wanted him to say right then, but it sure as hell wasn’t about coffee. She was hit by a fusillade of unsolicited memories: cases they’d worked; long afternoons they’d spent together, going over evidence or interviewing witnesses; meals they’d shared while they laughed and swapped stories and demonstrated the kind of support for each other that didn’t require words. Just a steady accumulation of days in each other’s company.

“One more thing,” he said.

Here it comes, she thought. Now he’d say something heartfelt, something about how he, too, remembered their daily interactions back in Acker’s Gap, and missed the camaraderie of a shared purpose. Missed, even, the impossible hours and the constant frustrations.

“No charge for the paper clip,” he said.

She gave him a brief wave to acknowledge the levity.

The front part of the store, when she rounded the corner and returned to it, was a different place now, with all three cash registers going full tilt, with lines of customers snaking around the racks and bins, waiting to pay for gas and gum and coffee and lottery tickets and peanuts and candy bars and sunglasses and cigarettes. Bell moved in a haze, preoccupied by her memories of previous mornings with Nick Fogelsong, work mornings, mornings when they’d felt the weight of the world but never really minded it because each had the other one right there, ready to take up the slack when one of them grew weary. The past was a tricky bastard. It called and called to you—and when you turned around and tried to grasp it, it disappeared.

Reaching the double glass doors, she took a quick look back at the busy store. She was mildly surprised to see the fat man—the one who’d walked in just ahead of her, the one in the green plaid coat and the cap with the oval Peterbilt logo—still on the premises. Must be stocking up. He stood at the start of the soft drink aisle, shoulders hunched, hands in his pockets, apparently torn by an existential dilemma regarding two-liter plastic jugs of Dr Pepper: diet or regular? The only visible motion came from his jaw, as it grappled with a bountiful plug of snuff, and his eyes, which roved restlessly.

Copyright © 2015 Julia Keller.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Julia Keller spent twelve years as a reporter and editor for the Chicago Tribune, where she won a Pulitzer Prize. A recipient of a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University, she was born in West Viriginia and lives in Chicago and Ohio.

Read this as an ARC – I love this series – this is her best yet – the writing is really superb – and the plotting in this one, based on an historical event, made me buy a non-fiction book about the Buffalo Creek Disaster of 1972 – just an excellent read!