Jack Vance’s Edgar Award: A Mystery Novel Wrapped in an Enigma

By Hector DeJean

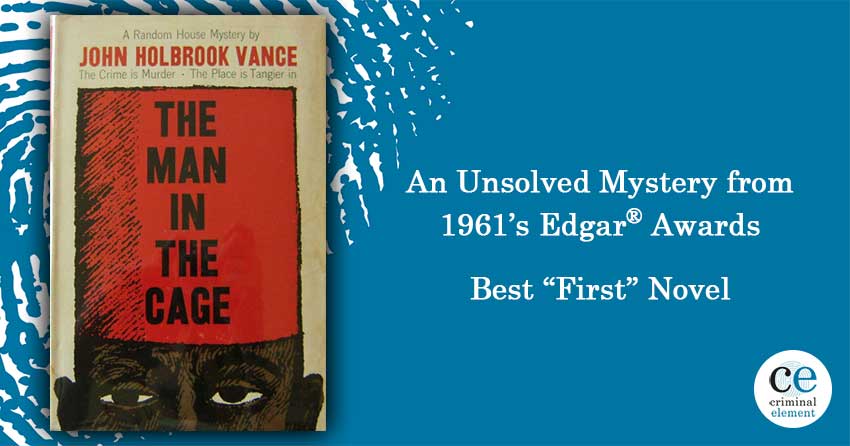

February 22, 2019Jack Vance won the 1961 Edgar Award for Best First Novel for The Man in the Cage. This was not his first novel—far from it in fact. Hector DeJean investigates.

Like many other distinguished science fiction and fantasy authors, Jack Vance won multiple Hugo awards, a Nebula award, a World Fantasy Award, and plenty of other honors. Unlike most other holders of these awards, Vance also has the highest award in the field of mystery writing, an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. The route to that award, though, starts out as an enigma, takes a detour through the strange chronology of Vance’s publishing history, and ends perhaps with a loophole.

Vance was extremely talented and prolific, publishing his first book, The Dying Earth, in 1950, and his last work of fiction, Lurulu, in 2004. In 1957, he published his first mystery novel, Take My Face, using the pen name Peter Held. Later that year, he published another novel, titled either Isle of Peril or Bird Island, under the name Alan Wade. (Different versions exist, and according to some Vance-ologists the book doesn’t really qualify as a crime novel.) A year later, he wrote his first mystery to be published under his full name, John Holbrook Vance. That book’s title, according to sources on the Internet, was Strange People, Queer Notions.

This is where things get odd. Following a trip to Morocco—Vance was as impressive a traveler as he was a writer—Vance wrote a mystery set in North Africa; John Holbrook Vance was the name on this one as well. The book was The Man in the Cage, and it’s quite good—I would even say it’s a standout book, especially for readers curious about Vance who might not care for the conventions of sci-fi and fantasy. The MWA agreed, and in 1961 they gave it an award, making Vance’s awards-shelf one of the more diverse of any American author.

Awarding Vance isn’t the weird part. It’s that the book won the Best First Novel by an American Author award, even though it was not Vance’s first book, nor even his first mystery. Other than it being a very well-done and worthy book, I wasn’t sure at first even how it was eligible for the award. Looking at the other Best First Novel winners from before and since 1961, it’s clear that the MWA’s standards have been continually strict; Fredric Brown had been writing for over a decade when he won the Best First Edgar for his novel The Fabulous Clipjoint. That book, though, was indeed Brown’s first novel, preceded by short stories, and Brown’s sci-fi novels came shortly thereafter. Likewise, Ira Levin seems to have had an impressive writing career before he won the Edgar for what is accurately his first novel, A Kiss Before Dying. Ditto James Patterson, Michael Connelly, and pretty much everyone else who picked up that particular honor.

But in Vance’s case, the award didn’t seem to fit. Was the MWA overlooking his previous mysteries? Did the judges honestly not know about the other books? Did the proliferation of pen names Vance used for his mystery books (In addition to Held and Wade, he wrote as Ellery Queen; I’m not sure when he began to publish mysteries under the name Jack Vance) leave the MWA confused about how many mysteries Vance had written prior to 1961? Were the standards for the Best First Edgar Award simply different then?

We’re revisiting every Edgar winner for Best Novel. Join us!

In any case, the MWA can pride themselves on acknowledging a worthy book by a talented author. The Man in the Cage opens as an American adventurer in Morocco wraps up a smuggling run, delivering a truckload of arms to rebels at the Algerian border. The run goes haywire when the adventurer, Noel Hutson, is given heroin as a payment instead of the cash he was promised, and he refuses to make the return delivery. (Noel also kills someone, but let’s not get bogged down in details.) Shortly before he vanishes, Noel makes some calls to people in Tangier and sends a letter to his brother, and that’s it—he’s apparently out of the picture.

Noel’s brother Darrell arrives in Morocco a month later to find the brother that no one has seen or heard from since the night of frantic calls. Darrell tries to confront the crooked hotel owner who set Noel up with the smuggling job, but that doesn’t get him anywhere, and Darrell begins to look for answers from a stool in the Masquerade Bar, where the expats in Tangier hang out.

The folks at the Masquerade are a memorable bunch, and several could know more than they’re letting on. Before Darrell can put his finger on the guilty party, he finds himself the guest of a Moroccan who worked with the rebels, and who locks Darrell in a cage after taking his passport to see if Darrell was part of what many suspect was a scam Noel was running on the side to fleece his bosses and the shipment’s recipients.

Darrell is up for all of the challenges he encounters. In addition to its main character, the book also features at least one of Vance’s most memorable heroines. I’ve criticized Vance in the past for usually treating his female characters as doormats, but the strong-willed Ellen McKinstry (niece of the crooked hotel owner), hostile to Darrell but eventually helpful, yet remaining a suspect anyway, is a nice break. Mystery novels are a great place to encounter dangerous women with secrets who may want to kill the protagonist or perhaps they just want to make themselves understood; Ellen arrives fully loaded with ambiguity and recklessness and adds a lot to the story.

Read More: 1961’s Edgar winner for Best Novel!

Vance had a special knack for describing complex settings and societies that would have seemed especially exotic to his readers in the 1960s, whether those places were on other planets or this one, and in The Man in the Cage he does a great job on that score again, giving a sketch of Morocco that’s enough to keep hold the story together, without being excessively wordy. It’s also the only Vance book I’ve ever read that refers to contemporary events, citing Gamal Nasser, Pan-Arabism, and Algeria’s FLN political party.

Given how well-traveled Vance was, he easily could have written many more mystery novels set in places across the globe, instead of using his journeys as the inspirations for interplanetary stories. The Man in the Cage is a glimpse of Vance’s talents in a genre separate from that for which he is best known.

So how did it win its award from the Mystery Writers of America—how did it even qualify for that award? It may have been because it was the first novel anyone ever saw attributed to John Holbrook Vance. Strange People, Queer Notions, the novel mentioned above that would eventually be published under the same name, may have been written before The Man in the Cage, but from all that I can tell, didn’t see print until 1985, almost three decades after Vance had penned it.

It appears Vance kept quiet about his previous two mystery debuts, under the other names; and it appears that the MWA didn’t consider books like The Dying Earth and Space Pirate relevant since they definitely weren’t mysteries. Vance’s victory may not be entirely on the up-and-up, given that his true first crime fiction novel was Take My Face. But if he was going to win via not-quite-on-the-level means, at least he did so with a very good mystery novel.

See Our Revisiting the Edgar Awards Series!

Comments are closed.

You’ve got the fact right. The Man in the Cage should not have been eligible for the First Novel Edgar, because of the two previous publications under the names of Peter Held and Alan Wade, neither of which is as good, both of which are readable. Strange People Queer Notions was published in a limited edition by Underwood and Miller, as were three other Vance mystery novels that had failed to find a publisher at the time they were written, for reasons unfathomable to this reader.

The Man in the Cage, incidentally, also received a TV adaptation, as an episode of Thriller, hosted by Boris Karloff. There also exists a TV movie of Bad Ronald, the most disturbing of Vance’s mysteries. Many vanceans will tell you that their favorites are the two Sheriff Joe Bain procedurals, The Fox Valley Murders and The Pleasant Grove Murders.

All of Vance’s mysteries, as well as his science fiction, are available as ebooks and print-on-demand paperbacks. See jackvance.com for more information.

I read Bad Ronald because George R. R. Martin said it was Vance’s best crime novel, and it was a turd of a book–the worst thing Vance ever wrote, in my opinion. Disturbing, yes, but also tedious–no tension whatsoever in the hunt for and capture of a criminal. And the criminal, by the way, isn’t remotely interesting or compelling.

De gustibus and all that. My favorite of Vance’s non-SF&F is The Dark Ocean, my least favorite is Bird Isle. I’d put Bad Ronald somewhere in the middle, as a well-executed character study. Very few of these titles are classic crime novels: the two Joe Bains, The Deadly Isles, The House on Lily Street, the three Ellery Queens. Sociopathic behavior, tending toward crime, is more of a common denominator. The best of them are quite good indeed, but I’m glad Vance found SF&F a more lucrative occupation.

Bad Ronald isn’t interesting as the result of anyone’s investigatory skill or pursuit. You are right on that count.

Ronald is a sociopath of the first order, seeing others, especially the children of the family who moved into his mother’s home, as possessions. The story is about his devolution as a parasite within the walls of that home, the fantasy world he creates, and his lack of compassion in general.

Before Bad Ronald was published in the early ‘70s accurate portrayals of sociopaths in fiction were rare. They were most often seen as automatons, slaughtering and remorseless until apprehended.

The psycho, Harry Lime, in Greene’s The Third Man regards humanity as an ant hill seen from his great elevation as a collection of ‘dots’. Who cares if Lime’s black market penicillin causes one of the dots to stop moving? Jack Vance brought those ‘dots’ very up close for Ronald’s tender ministrations.

Vance took time and imagination to flesh out the transition from reality into Ronald’s magical Atranta, complete with personalities and an internalized code of behavior. Vance makes the reader understand the psychotic point of view, much as Sandford’s Rules of Prey did years later. He was prototyping the deeply alienated and resentful villain who would appear in many guises in subsequent Vance mystery and science fiction works. It is the sense of brooding and inevitable dread Ronald imposes on his surroundings that makes the story.

Maybe not your cup of tea, but lots more flesh on the carcass than your dismissive summary would indicate.

Michael Connelly won an Edgar for best first novel ,not any connoly

I don’t imagine that Vance’s earlier sf novels would have disqualified him from getting that Edgar, since I presume only “first published *crime* novel” was what was being considered. But of course you’re right that the earlier pseudonymous novels (as I recall, the Wade ISLE OF PERIL does qualify as a ‘crime novel,’ though not a mystery; the Held is both) should have done so. But I suspect that the MWA voters (or vote vetters) might indeed not have known of those two earlier books; even a few years later when I started being a Vance fanatic, it took me a while to learn of their existence.

I’d think one reason STRANGE PEOPLE, QUEER NOTIONS failed to find a publisher in the late 1950s is that its big secret is based on a biological impossibility. Certainly rather spoiled it for me.