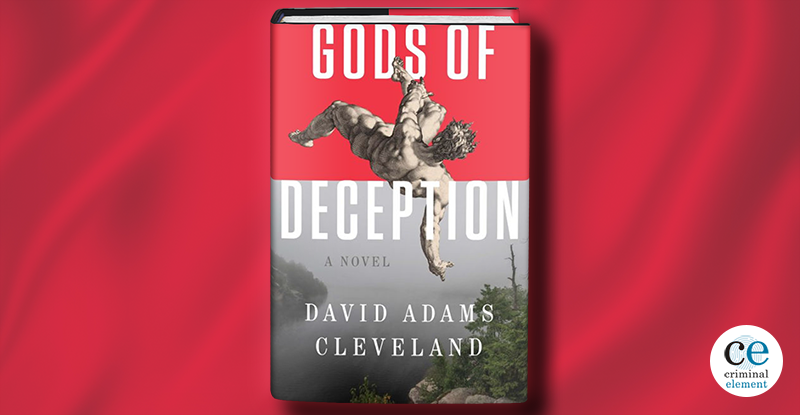

Gods of Deception by David Adams Cleveland: Featured Excerpt

By Crime HQ

April 26, 2022

“In the early days of the Cold War, many Americans simply could not believe that a perfect gentleman like Alger Hiss could be a Red spy. David Adams Cleveland uses his gifts as a storyteller to imagine deeper human truths behind the headlines. Gods of Deception is a lushly vivid tale of a haunted time.”

—Evan Thomas, author of The Very Best Men and Being Nixon

CHAPTER ONE EXCERPT

We are caught in a tragedy of history.

—Whittaker Chambers

JANUARY 21, 1950

ASSOCIATE COUNSEL FOR the defense Edward Dimock, summer tan attractively faded beneath his chestnut hair, sat forward at the defense table as he inspected the twelve jury members filing back into the federal courtroom templed above Foley Square. He cocked his head, squinting, like the expert birder he was, off-blue eyes attentive to any telltale clues in the rapt faces of the eight women jurors, finding himself relieved at the serious, if not severe, freshly lipsticked frowns telegraphing from the oak-paneled jury box. He checked his watch and then the brass wall clock above the jury room entrance: 2:46—twenty minutes since lunch break. (A configuration of hands, an angle of 165 degrees, to be exact, that would forever become annealed in his mind’s eye.) He nodded mechanically, as if a switch in a finely tuned mechanism had been tripped. Forty-three years old, now at the height of his powers, a few gray strands in the upturned flourish of his eyebrows for gravitas, he pensively rested his jaw on his fist.

No, certainly not much in the way of indecision on display, and even less in the forthright stare of jury forewoman Mrs. Ada Condell, who waited grimly in her seat for the judge to inquire as to their verdict. These and other portents of disaster caused Edward to glance down the defense table to where his client, Alger Hiss, sat with stoic determination next to his wife, Priscilla. Her familiar upturned nose and quivering, compressed lips caused Edward’s pulse to quicken, and he ground his fist against the sharp angle of his chin, repressing the urge to gasp out a warning, while bracing himself for the worst. Below, the vague tremor of traffic or the rattle of a subway train vibrating the floor. On the mocha plane of his half-drunk coffee, a ripple moved. Yet another avatar of cosmic cataclysm, which Judge Henry W. Goddard seemed to savor: what the newspapers already heralded as the trial of the century, even a century only half done. Goddard paused again, absorbed in his own little drama of shuffling papers on his bench, per- haps girding himself for the sure-to-come uproar in the aftermath of this four-week ordeal, a thing anticipated by the hundreds of reporters stacked to the coffered ceiling of his courtroom, peering forward as one with pens raised, breath suspended . . . while grave Fortuna, coiled catlike, ready to spring in the left front corner of the jury box, awaited her moment on history’s stage.

Given a moment’s respite (shuffle, shuffle), Edward lifted his gaze to the dull liquid January light flooding the fantail window above the jury box, thirteen stories above Foley Square and the teeming metropolis where he and his father before him had mightily prospered. Yet there was nothing in that cloudy gray to give him pleasure, except thoughts of escape on ardent wings to Hermitage, his Catskill retreat—now, today, in an hour or less, with Annie and the girls and Teddy (all still on Christmas break, the girls from Chapin and Teddy from Yale). Closing his eyes for an extended tattoo of heartbeats, he sought to rally the moral gravitas and professional competency that Groton, Yale, Harvard Law, a treasured clerkship with Oliver Wendell Holmes, his position as top gun at Beekman-Morris, and three years on the War Production Board in Washington had long instilled, the experience and finely honed instincts that now prompted him to abandon his longing gaze for the sullen emptiness of the witness box. He sighed as he contemplated one final time that stage setting, where, only days before, he’d deployed the unctuous theories of psychopathic personality disorder and unconscious motivation against the prosecution’s star witness, onetime ex-Communist and Time magazine editor Whittaker Chambers, with the ghastly results to be confirmed momentarily.

That afterimage still pressed on his guilty soul: Chambers seated in his unpressed trousers, dirty shirt collar curled over his seedy jacket, scuffed shoes. Those deep-set sleepless eyes, sad and tortured yet brimming with the wisdom of the solid earth . . . a man of sorrows, a prophet of doom, who now invisibly inquired of his persecutor about the sad fate of the artist, one George Altmann, on Christmas Eve, a short four weeks before. Chambers’s testimony had craned the necks of jurors and judge alike: hushed, reticent, searching, laconic; a voice that would haunt Edward Dimock all his days, living on to captivate him in years to come from the pages of Chambers’s best-selling autobiography, Witness.

Edward Dimock’s beleaguered inspection of the witness box deepened with regret as he recalled yet again the ineptitude and inquisitorial overreach he’d foolishly undertaken at Alger Hiss’s promptings and assurances—if not vague threats, something his mentor Justice Holmes would have severely chastised him for. “Son, once a man’s reputation is besmirched, threats or no” Edward winced with the pain of one who had disregarded his betters, if not his better instincts, thereby trashing what little remained of his, much less his profession’s, pretension to a moral code.

He reached to the heavy briefcase by his leg, if not for assurance, possibly in prayer that he might be spared the full implications, if not deployment, of what lay concealed within.

A cough, a clearing of the throat, and Edward, starting from reverie, looked to the acanthus-carved bench where, papers finally shuffled, the experienced and respected Honorable Henry Goddard prepared to proceed, arraying his silver-bespectacled aquiline profile to full effect, only to begin a quick inventory of the rapt congregants crowding his oak-paneled courtroom.

A wave of relief washed over Edward that the thing was now out of his hands: that twelve ordinary Americans would do their duty and pronounce a verdict that might contradict the expectations of some of the finest legal minds and savvy commentators of his generation— august public servants and gilded pundits all—and, in turn, repudiate the most astute lawyering money and reputation could buy (the like of which he’d never dreamed possible), thus shifting or at least sharing the blame for his egregious and smarmy psychiatric hucksterism employed at Chambers’s expense. Hadn’t all the Harvard boys on the defense team signed off, in the end? Hadn’t their outrageous ploy been indulged by Judge Goddard? Even if only to even the score by allowing the prosecution to call ex-NKVD agent Hede Massing as a witness, and so fingering Alger dead to rights.

Petite, doe-eyed, redheaded Hede, so Edward assured himself, with her warm and melodic Viennese cadences, had surely sunk them anyway, along with the Hisses’ black maid, Claudia Catlett, and the irrevocable evidence of the purloined secret State Department papers copied on the Hisses’ Woodstock typewriter. Surely the facts, as facts always do, would, in the fullness of time, extract the barbed hook of infamy from a career now in dire jeopardy.

Edward concentrated once again on Alger and Priscilla Hiss, as if for a final reckoning—and for Alger it would be the last time—before history weighed fully, if ambiguously, in the scales of justice. That agile kitelike face (yellow-billed), rigid with righteous indignation, with an air of detached concentration—expensive winter suit, starched shirt with French cuffs always discreetly hidden, soft, becoming tie, and shiny black shoes—swept Edward back to the day only two months before when Alger strode into his Beekman-Morris office to make the case for accepting the role of associate defense counsel (slated for one singular task) in his second perjury trial, equally cajoling and flattering and so, so subtly threatening. Even pressing Priscilla into the act—and it had always been a paired-horse marriage—at their rendezvous in Riverside Park. The still lovely though desperately anxious Pross on her lunch break from Dalton, taking his hand tenderly and pleading the good cause with tear-verging blue eyes, those same strong and so agile fingers—touching his for quick moments—that had clandestinely cantered across the keys of the green Woodstock typewriter, which, even now, stared back like some bleak totemic object of the industrial age from the evidence table next to the jury box.

The thought of all those top-secret State Department documents made for another moment of serenity, a half-smile as Edward loosened his tie: damning evidence produced like a conjurer’s trick by Whittaker Chambers and thus, truth be told, dooming their case from the get-go. With the testimony of that mysterious Red pixie Hede just the icing on the cake, along with the Hisses’ Negro maid. Edward sighed as he again scrutinized the rapt face of the jury forewoman: a final confirmation that, professionally speaking, he’d done the necessary—defending his family—and canny thing in face of insuperable obstacles, even as those damned Altmann sketches had blindsided him. And with this bit of self-assurance, he reached under the defense table to his leather attaché case once again and gave it a reassuring pat that his insurance (nine portrait sketches by the recently deceased artist George Altmann) would not now, not ever— thank God!—require deploying.

So, let history be his judge and jury. Even if the brass clock over the door to the jury room seemed to have barely moved. Even if his wife, Annie, had barely spoken to him in a month, after dutifully sitting in on the first day of the trial. Even if his beloved son, Teddy, had avoided him all Christmas, preferring to spend his time with his Yale roommates in the city. Time and sunlight were the final disinfectant of one’s integrity.

Lengthening his focus just above Alger’s cleanly parted hair, he caught a glimpse of his opponent at the prosecution table, Assistant U.S. Attorney Thomas F. Murphy, formidably tall even when seated, his dark mustache flexing optimistically as he stared down at the number-two pencil in his hand with the unshakable confidence of one who’d already caught the glint of the executioner’s raised ax.

The rest of the defense team, Cross and McLean, remained rigid, perspiring, having read those twelve faces as well as he had.

Judge Goddard nodded at the court clerk, who leaped to his feet as if from a jack-in-the-box and demanded the verdict.

“How find you?”

Ada Condell didn’t wait a beat, thus heralding in the chaotic world that would become the Red-baiting McCarthyite decade of the 1950s. In a choked, then clearing high-pitched voice, she declared, “We find the defendant guilty on the first count and guilty on the second count.” Oddly, Edward wanted to reach out a steadying hand to Alger, his onetime Harvard Law confrere and fellow birder, but found him rigid, with arms folded, stiffened brows and clenched lips impervious to time as well as to history, as one hundred-plus pens in the press gallery swept across acres of spiral notepads. Priscilla barely blinked, her traumatized gaze flashing to the wintery space of light from the fantail window, her prim shoulders bent, hands crossed limply in the silk folds of her lap. If he could have spoken to her, this was the query that hovered on his lips like an incantation out of time itself: Oh, my dear Pross, how far from Handytown now?

And with that, he gave his attaché case yet another relieved pat.

Of the following fifteen minutes of instructions to the jurors not to blab about their deliberations, and a quick to-and-fro over the five-thousand-dollar bail, Edward found in later years that he remembered almost nothing. Only a final image of Alger grabbing Priscilla’s hand, whispering in her ear, “Keep your chin up,” and leading her quickly out past the horde of snarling reporters.

With that verdict of dishonor and ruin, Alger exited Edward Dimock’s life, as if he’d never been, which, upon deeper reflection, might indeed have been the case.

For as Edward would remember until his dying day, his thoughts at that moment flowed along these lines: A man who lies so expertly, so convincingly, who threatens with the merest inflection of voice, rarely treads the boards of this life, and then only in pursuit of his spectral shadow. Or as his grandson would put it to him some fifty years later: “Judge, it was as if you inhabited two different stages, two parallel universes; and I’m not entirely sure, even now, if you know the difference.”

Copyright © 2022 by David Adams Cleveland. All rights reserved.

Comments are closed.

I found this post very interesting and informative. Thank you for sharing your special thoughts with us. I definitely share this with my peeps.

TradeKey is the world’s prominent and fastest developing online business.

Pg Slot เว็บตรง แตกไว สล็อตน่าเล่น มีเกม สล็อต เว็บไซต์ตรง แจกเครดิตฟรี ให้เลือกเล่นล้นหลามมากมายแบบอย่าง เสมือนเลียนแบบแหล่งคาสิโนจากสถานที่จริงๆมาไว้บนโทรศัพท์เคลื่อนที่

I have read your article, it’s very informative and helpful for me. I admire the valuable information you provide in your articles. Thank you for posting it.

I am really happy to have found this site at last. Really informative and meaningful activities, Thanks for the post and effort! Please continue to share more as a blog. I have now saved it to my bookmarks so I can keep in touch with you.

cool website, its very very interesting like mine in main303 Slot Gacor

Hey, I’m Jhonny Deep, and I manage to be responsible for developing and executing marketing strategies that drive sales to business-to-business companies.

Really helpful. Much to learn from the post. Thanks a lot for sharing an amazing content

I’ve seen some excellent points here. Amazing stuff, I believe you brought up some excellent points. Continue your wonderful work.

Such a usefull info thanks for sharing this within us .

I’ve seen some excellent points here. Amazing stuff, I believe you brought up some excellent points. Continue your wonderful work.

Write For Us Digital Marketing is a digital marketing agency. They offer a wide range of services to help their clients with their marketing needs.

A scalp vein set called a “Scalp Van Infusion Set” is perfect for injecting tiny volumes of infusion solutions into blood samples. Pediatrics and the treatment of individuals with contractures both regularly employ it. The disposable scalp vein set suppliers is used for venipuncture and intravenous infusions.

Our embroidery digitizing in cheap prices know how to properly digitize a logo based on factors such as fabric, textures, sizes and threads. Most of our staff has been trained in graphic designing or applied art and have an artistic vision to convert your artwork into beautiful embroidery.

The fiber obtained from cashmere goats, pashmina goats, and some other breeds of the goat is known as cashmere wool, or simply cashmere. Cashmere fabric suppliers were already noted, the Cashmere goat, which can be found in Mongolia, China, India, Iran, and other locations, is the “provider” of cashmere wool.

Great post dude.

Hello! Writers, our community is always looking for new voices to contribute to our premier startup platform.

pg slot Big web slots, PG, with a fast automatic deposit-withdrawal system within 8 seconds.

Fantastic article. Your works are distinctive, easy to understand, and contain informative and inspiring material. Keep up the fantastic work!

you are my inspiration The content you create has attracted me.