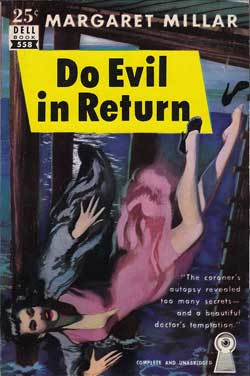

Note: This post kicks off a series celebrating the career of one of mystery fiction’s true giants, beginning with the novel Do Evil in Return.

This month marks the centennial of the great Margaret Millar. At her peak, Millar was about as successful as a mystery writer could be. She published 27 books, won the Edgar for best novel (twice), served as president of the Mystery Writers of America, and won the Grand Master Award for lifetime achievement. Her fan base was so notoriously fervent it caused one critic to remark, “Millar doesn’t attract fans; she creates addicts.”

All of which makes it remarkable that Millar isn’t as well known today as she should be. The reason for this, ironically enough, is bound up in one of her strengths as a writer: she did a little of just about everything. She wrote noir novels, hardboiled novels, classical whodunits, suspense novels, and pitch black comedies. She wrote books about women. She wrote books about men. One of the primary joys of being a Millar addict is that you never know what you’re going to get, and this very unpredictability is probably the reason that she remains a cult figure today. You can’t pin her down the way you could with—oh, just to pick an author completely at random—Ross Macdonald. Yet the personality, the authorial voice, of her work remains remarkably consistent. Mordant, inventive, and psychologically curious—the chief characteristic of her writing is quality. That’s why Millar attracts addicts. You never know what you’re going to be get, but you know it’s going to be pretty damn good.

Her best noir novel is probably 1950’s Do Evil In Return. It tells the story of a doctor named Charlotte Keating who turns away a young woman looking for an illegal abortion. Later that night, Keating starts to feel bad about it and tries to track down the girl, Violet O’Gorman, only to discover that she’s missing.

The book follows Keating as she attempts to find out what happened, but the deeper she goes, the more her life seems to intertwine with the history of the dead girl. As is so often the case in a Millar novel, the hero has a complicated personal life. Unlike the relatively autonomous protagonists of so many mystery novels, Millar’s characters tend to be locked into a series of complex relationships (in something like 1945’s The Iron Gates, they seem absolutely trapped). Keating is sleeping with Lewis Ballard, the husband of one of her patients, Gwen—and their already shaky liaison gets thrown further off balance when Keating starts to get close with Lt. Easter, the cop assigned to the case.

Charlotte Keating is one of Millar’s most compelling protagonists. She’s smart and capable, but like all noir heroes, she’s at the mercy of her own decisions—not just her decision to turn away a young woman in need, nor the decision to have an ill-advised affair with a married man, but the accumulated decisions of a lifetime. And hers is not a life that’s been lived particularly poorly, either. Keating isn’t a burn-out or a deadbeat, just a normal woman at the mercy of time and loss, a victim of the reality that everything we do has unforeseeable consequences. At one point, the cop Easter is trying to talk her out of her suspicions. “I think the real reason you don’t want to believe that Violet killed herself,” he tells her, “is that it would leave a scar on your conscience.” Her response is an almost perfect distillation of Millar’s worldview:

“That’s what a conscience is made of, scar tissue,” Charlotte said. Little strips and pieces of remorse sewn together year by year until they formed a distinctive pattern, a design for living.

One of the great strengths of Do Evil In Return is the aura of dread that hangs over everything. At the opening of the book, this overhanging anxiety is quite literal:

The afternoon was still hot but the wind carried a threat of fog to come in the night. It slid in through the open window and with curious, insinuating fingers it pried into the corners of the reception room and lifted the skirt of Miss Schiller’s white uniform and explored the dark hair of the girl sitting by the door. The girl held a magazine on her lap but she wasn’t reading it; she was pleating the corners of the pages one by one.

Here Millar sets up a world that will prove to be a relentlessly sinister place, a place where even a hot California afternoon is menaced by an encroaching darkness. The craft is impeccable—evocative and economical, establishing a tone of unease while introducing the scene of a nurse and a patient awkwardly sharing space together, landing finally on the small nervous image of the girl turning down the pages of a magazine.

As is so often the case with a Millar novel it’s difficult to talk too much about the plot without giving away the pleasure to be had in all its twists and turns. While a Millar novel will often end (sometimes in the final sentence) on a sudden revelation that reconfigures everything that has gone before, this is not the case with Do Evil In Return. Yes, the final chapter reveals the solution to several outstanding mysteries, but the feeling at the end isn’t a sense of relief so much as a permanent melancholy. Far more than most mystery writers, Margaret Millar knew that life itself was a mystery without a solution.

Jake Hinkson is the author of several books, including the novel The Big Ugly and the newly-released short story collection The Deepening Shade.

Read all of Jake Hinkson's posts for Criminal Element.

PS. Next up: Millar’s 1955 BEAST IN VIEW