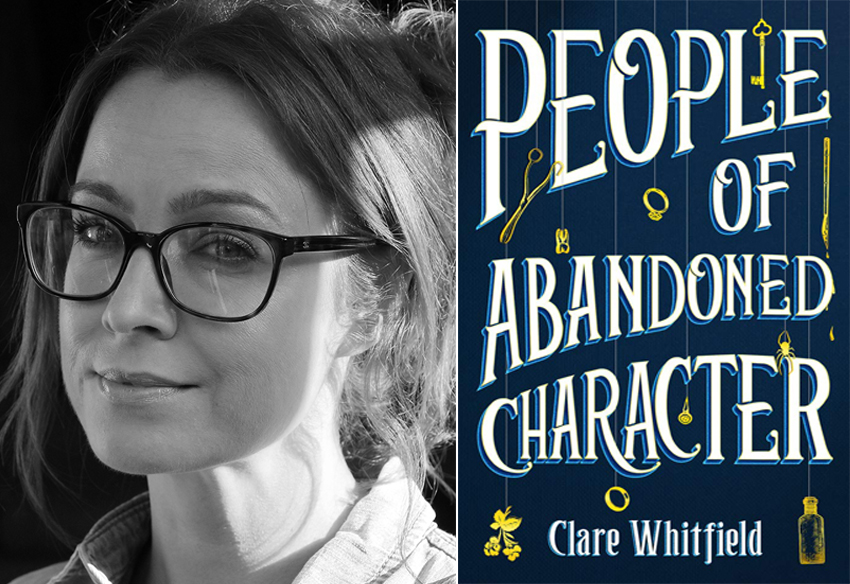

Clare Whitfield on Marriage, Class, and Jack the Ripper

By Clare Whitfield

April 29, 2021

The idea for People of Abandoned Character, a story about a woman who thinks she may have married Jack the Ripper, came from a night class at a local college. The teacher had handed out newspaper clippings from 1888 reporting the murder of Polly Nicholls and we were asked to write from the point of view of someone living at the time, but it couldn’t be a policeman or victim. I chose what I thought was the next obvious person—his wife. It got such a strong reaction from the class that the idea stayed with me. It haunted me on occasion, like the ominous figure himself. So what better way to cathartically work out this demon than by making it the subject of my debut novel.

At the center of the story is a toxic marriage. When someone is married to an abusive partner today, we understand it’s hard to leave, but in class-ridden Victorian English society in 1888 it was nearly impossible, especially for women. What if your husband is better connected? What if you have no one to run to, no refuge or welfare, or even the opportunity to earn a decent living. How do you “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” as the wealthy kept telling the poor? The numbers don’t stack up. That’s what my main character, Susannah, must work out if she is to survive her terrible marriage.

I started to research not only about the murders but about the cultural landscape. It struck me how similar the social-economic situation was to today. There was the same crazy hand-wringing from self-appointed social commentators about how the country was getting worse. The national culture was being eroded from within by the invasion by foreigners or radicals with their strange tongues and ideas. Society’s morals were declining and most importantly— who was to blame?

It became apparent that the better classes honestly felt as if they were going to be overrun. That their way of life was at threat. I think that’s like today too. But there was no mystery to solve. The rising tide of anger came from years of grinding systemic poverty and fermenting rage at a rigged class system. Britain may have been at the peak of the Empire, but the wealth was hoarded in the hands of a few who believed everything they had was down to innate superior intellect and good breeding, and absolutely nothing to do with starting a hundred-yard sprint at the 99th yard.

In a funny way, Jack the Ripper did what social reformers had failed to do for years—shine a light on the state-sponsored neglect of the poor. Wilful demonization of the poor is something we have a long tradition in, but I don’t feel any sentimentality about it. I just think that when we look back at our histories—personal or national—we have an obligation to own the whole truth, not just the bits we get fluffy and warm about. We should acknowledge the good and bad because that’s what all humans are.

I took so many notes and had files and files of research—about every aspect of the era, nursing, the health system, politics, lunacy, and the murders. I read about Victorian houses and studied guidebooks for newly married housewives. I read books on fashion, underground societies and I wandered around Whitechapel and went on a Jack the Ripper tour. Researching the murders was the easiest part—I was sticking to the reported news items and there weren’t that many victims. But what paint would Victorians have on the walls or what were their bathrooms like? Did they commute? (Yes.) And what was the travel system like?

I expected to read about extreme poverty, a rigid class system, and women being second-class citizens since so many rights, such as voting, didn’t come until years later. I wasn’t even surprised to learn about the lunacy laws that meant people could be interred in private-run for-profit asylums if they could fudge the necessary paperwork. What I didn’t expect to learn was that nursing was only recently regarded as a respected profession. My main character starts her story as a nurse at the London Hospital in Whitechapel and I really enjoyed learning about the formidable Eva Luckes, a confidant of Florence Nightingale, who became matron at the age of twenty-six and undertook huge nursing reforms and turned it into a skilled and respected profession at the London Hospital. This was part of a wider coordinated effort by a gang of women like Luckes and Nightingale, to define nursing as a skilled trade with a decent wage and benefits and achieve true independence and respect for their nurses.

Writing a novel of historical fiction felt like a huge undertaking but in the end, a lot of historical detail came out during the editing process because the story must come first. While it was interesting, it was an invaluable lesson in balancing research and storytelling.

Buy People of Abandoned Character here:

Comments are closed.

the knot tightened instead of loosening making it more difficult to untie. The groom, had a nervous laugh. I think he began to sweat. People began to see what was happening and also joined in the laughter at his predicament.