If The Long Good Friday (1980) is the British crime film that captures the entrepreneurial spirit percolating in Britain just before Margaret Thatcher's ascension to Prime Minister in 1979, a harbinger of the aggressive free market days to come, then director Antonia Bird's Face serves as the bookend to the Thatcherite era. Shot in 1996 as the John Major led Conservative government was fading and released in the changed political world of fall 1997, after Labor Party Leader Tony Blair had taken power, Face is a heist-gone-wrong tale that sheds a bleak light on the era's values and what those values left behind.

If The Long Good Friday (1980) is the British crime film that captures the entrepreneurial spirit percolating in Britain just before Margaret Thatcher's ascension to Prime Minister in 1979, a harbinger of the aggressive free market days to come, then director Antonia Bird's Face serves as the bookend to the Thatcherite era. Shot in 1996 as the John Major led Conservative government was fading and released in the changed political world of fall 1997, after Labor Party Leader Tony Blair had taken power, Face is a heist-gone-wrong tale that sheds a bleak light on the era's values and what those values left behind.

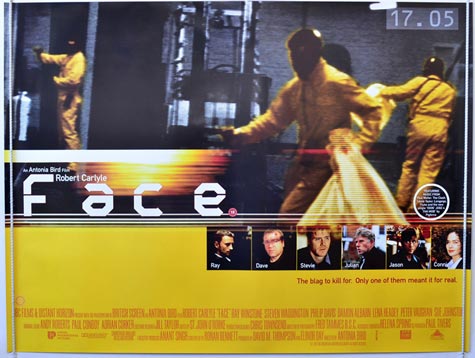

Set in London's dingy East End, where Antonia Bird lived for several years, Face follows Ray (Robert Carlyle), the nominal head of a five-man group that plans to rob a security depot. Their expected haul: two million pounds. Four of the five men know each other well, and the fifth is the nephew of a long-time confederate of the other four.

Ray and Dave (Ray Winstone) clearly have done a lot of jobs and carry themselves with a measure of professional assurance. Julian (Philip Davis) also has experience, but an erratic temperament. Stevie (Steve Waddington), is a big, gentle guy who's a bit slow in the head and who Ray takes care of like a brother. Jason (musician Damon Albarn in his movie debut) is the group's cocksure rookie. A somewhat motley crew who do a job that doesn't bring them the haul they expected, that falls apart in betrayal and acrimony—the film's basic plot bears the influence of Resevoir Dogs, released five years earlier. But where Tarantino's film focuses on its characters only insofar as they relate to their heist and its consequences, Face looks at its criminals in a wide social context.

Ray and Dave (Ray Winstone) clearly have done a lot of jobs and carry themselves with a measure of professional assurance. Julian (Philip Davis) also has experience, but an erratic temperament. Stevie (Steve Waddington), is a big, gentle guy who's a bit slow in the head and who Ray takes care of like a brother. Jason (musician Damon Albarn in his movie debut) is the group's cocksure rookie. A somewhat motley crew who do a job that doesn't bring them the haul they expected, that falls apart in betrayal and acrimony—the film's basic plot bears the influence of Resevoir Dogs, released five years earlier. But where Tarantino's film focuses on its characters only insofar as they relate to their heist and its consequences, Face looks at its criminals in a wide social context.

No glamour or luxury touches these men. They own ordinary cars, live in drab flats, and hang out in neighborhood pubs. They have to deal with daughters and wives, girlfriends and mothers, and they fumble around in these relationships, not always sure of themselves.

Ray tells someone that he was “working honest” till he was twenty four. And through brief flashbacks and the conversations he has with his girlfriend Connie (Lena Headey), we learn of a time when he had ideals. He was a socialist, a trade union activist who attended protests against the government machine. It’s obvious that he inherited his leftist sympathies from his mother, Alice (Sue Johnston), who remains committed to the cause, as does Connie. His mother, even now, day after day, is busy going to a demonstration against the impending deportation of two Kurdish nationals, Communists. Connie is facing budget cuts that will close the home for parentless boys she helps run. Despite the headache of her struggle, it’s obvious Connie will continue battling, and later we see her attending the pro-Kurd rally with Ray’s mother. So it appears that the options of going into crime or giving in apply more to inner city men than women, and Ray has enough perspective on his life to comprehend its ironies.

During the robbery, a scene shot and edited beautifully, the five criminals in their yellow jumpsuits, faces covered, terrorize the people in the security depot. They’ve just smashed their way in with a truck altered into a battering ram, and they yell at the employees, threaten them, wave their guns in people’s faces. They're very effective and no one there opposes them, tries to be a hero. But later in his thoughts, Ray contrasts this vision of his stormtrooper self with his memories of the club-wielding cops brutalizing him and like-minded protestors during times gone by. We understand that Ray is grappling with the question of what the hell happened to him and how he wound up doing what he’s doing. Not that he’d admit these doubts to anyone, least of all his girlfriend. When she asks him to accompany her to a protest, he replies “that's not me” and that no matter what he was once, he's moved on. “We've all moved on,” Connie says. “It's what we've moved on to that counts.”

During the robbery, a scene shot and edited beautifully, the five criminals in their yellow jumpsuits, faces covered, terrorize the people in the security depot. They’ve just smashed their way in with a truck altered into a battering ram, and they yell at the employees, threaten them, wave their guns in people’s faces. They're very effective and no one there opposes them, tries to be a hero. But later in his thoughts, Ray contrasts this vision of his stormtrooper self with his memories of the club-wielding cops brutalizing him and like-minded protestors during times gone by. We understand that Ray is grappling with the question of what the hell happened to him and how he wound up doing what he’s doing. Not that he’d admit these doubts to anyone, least of all his girlfriend. When she asks him to accompany her to a protest, he replies “that's not me” and that no matter what he was once, he's moved on. “We've all moved on,” Connie says. “It's what we've moved on to that counts.”

It's the first of the series of bloody betrayals that ultimately destroys the group, and the core motive behind each betrayal is the same—greed. Ray's group has succumbed to the same every-man-for-himself mentality the government's been promoting for years. Everyone seems demoralized in this environment, and no one sums up the infection better than a thoroughly corrupt cop: “There are no public servants. There is no public service. All there is is money and the people who have it.”

What may or may not save Ray is the self-awareness he has that his fellow robbers don't. And despite his remarks to Connie that he's moved past the time he believed in a certain solidarity with others, we see that he hasn't abandoned this position entirely by how he looks out for Stevie. He and Stevie live in the same house, and the devotion he shows to Stevie, the responsibility he feels toward his somewhat simpleminded friend, is a sure indication of the humanity left in him.

Face is one of the few British crime films (or crime films from anywhere) directed by a woman. Would you be able to guess this fact if you didn't know it before you watched the movie? I don't think so. But what does come across is that Face doesn't have a single clichéd female character. Antonia Bird, working with Ronan Bennett's script, gives us no molls, no hookers, no femme fatales. There aren't any idealized women either. Yet it's notable how much the story's women influence the thoughts and actions of the men and how the men openly acknowledge the importance of the women in their lives.

What a great touch it is when Ray and Julian converse about women during a free minute they have. On the hunt for the person they think betrayed them, about to go into a house with their guns drawn, they chat for a bit about what a man has to do to keep a woman. It's mad-dog Julian doling out the advice, which makes what he says that much more surprising. All women want two things, he tells Ray. The first thing is passion (the no-brainer of the two, as he describes it), and the second thing is the secret to success—kindness. Kindness “goes down really well,” he says, with utter sincerity, to which Ray can only agree.

With its political message, Face runs the risk of being heavy-handed, but its pacing and tension prevent that. So do the outstanding performances by everyone involved; all the major players went on to long careers in film and TV, and no wonder. It's a pleasure to watch the ensemble cast deliver the goods in that realistic British-acting way. Humor lightens the film as well, much of it from Philip Davis as the unpredictable Julian, but it's a dry, low-key humor, never winking at the audience. We're a long way here from Guy Ritchie's films, or Tarantino's for that matter. Combine all this with an apt score that comments on the action and London itself—Billy Bragg's Waiting for the Great Leap Forward, Paul Weller's Everything Has a Price to Pay, Gene's London Can You Wait?, Puressence's Standing in Your Shadow, many others—and you have a solidity that makes for a layered drama.

It's the only crime film Antonia Bird ever made (After a long directing career, Bird died in October, 2013 at 62 years of age), but her one contribution to the field serves as a sharp and entertaining look at a slice of Britain put through the wringer by the Thatcherite years.

Some images from Vagebond's Movie Screenshots.

Scott Adlerberg lives in New York City. A film nut as well as a writer, he co-hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series each summer at the HBO Bryant Park Summer Film Festival in Manhattan. He blogs about books, movies, and writing at Scott Adlerberg’s Mysterious Island. His Martinique-set crime novel, Spiders and Flies, is available now from Harvard Square editions at Amazon, B&N, and wherever books are sold.