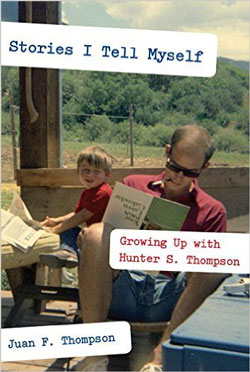

For anyone who has an impression of the kind of lifestyle Hunter S. Thompson led, the notion of him being somebody’s father can be disconcerting. The drugs, the guns…I don’t recall any Gonzo parenting sections in the guides I’ve read about best practices in raising children. Juan F. Thompson, who was born in 1964 and is the only child of HST, both confirms the suspicions most of us would have about his famous dad’s parenting ways, and shows us sides of HST that many will find surprising.

Juan doesn’t hold back in describing the difficult times of his childhood. The hardest era for him seems to have been when his parents, who split from each other when he was a pre-teen, were still together. When Juan describes episodes from this time of his life, we see the worst in his father. We see HST abusing his wife in various ways, then becoming a manipulative good old boy when she calls the local police for help, assuring the cops that everything is just fine in their household—the little lady just had too much to drink and doesn’t know what she’s saying. Juan offers blunt statements about his dad, such as, “He was a very bad man who tormented my mother, whom I loved dearly and depended upon.”

However, the father-son relationship improved after the couple’s divorce. Although there were still plenty of difficult times for Juan as Hunter S. Thompson’s offspring, there were also more harmonious and “normal” moments between father and son. Through Juan’s remembrances, we see things like HST becoming giddily excited at the prospect of his son’s wedding engagement, being a loving grandfather, and having rituals with his son like the two of them enjoying classic movies together (part of the movie-viewing tradition was that they cleaned guns while watching the films, and while that might not be something Ward Cleaver would do with Wally and Beaver, it was a bonding experience for HST and Juan).

Sometimes the father’s concern for his son’s well-being manifested itself via HST calling on friends to take Juan under their wings for a time. One time, he got Jimmy Buffet to take Juan on a month-long sailing expedition, to remove him from the fray of HST’s stormy world. Here’s Juan, who has a son of his own, reflecting on parenting:

What do fathers want most from their sons? Do we only want them to be happy? Do we want them to be like us? Do we want forgiveness? Do we want them to be better than us in love, work, money, fatherhood? Do we want to be loved by our sons? Is it enough that they want to still talk to us when they grow up? I don’t know what my father wanted from me? He was happy when I graduated with honors from college; he was happy when I got married to a woman he respected; he was thrilled when my son came along. I know he was glad I was able to support myself and that I wasn’t a drunk or drug addict. I know he needed my forgiveness.

Despite the book’s subtitle, not all of the content directly involves HST. This is Juan’s life story from the time of his birth until his father’s death by suicide in 2005, and there are whole sections that don’t really have anything to do with HST. Still, the narrative never gets too far away from the son’s reflections on his father’s character and their relations with each other. Even when Juan tells of times in his life in which his dad did not play an active role, the shadow of HST still looms. And when Juan stays focused on his dad, there are segments that anyone interested in HST will find absorbing, like:

Despite the book’s subtitle, not all of the content directly involves HST. This is Juan’s life story from the time of his birth until his father’s death by suicide in 2005, and there are whole sections that don’t really have anything to do with HST. Still, the narrative never gets too far away from the son’s reflections on his father’s character and their relations with each other. Even when Juan tells of times in his life in which his dad did not play an active role, the shadow of HST still looms. And when Juan stays focused on his dad, there are segments that anyone interested in HST will find absorbing, like:

Though he is often called an iconoclast, my father had a superstitious temperament. He found comfort in ritual, as I do. He wasn’t religious in a conventional sense, but he believed very strongly in an inherent moral order and in the concept of righteousness, and he believed in unseen forces that enforced that order.

Throughout the book, Juan drives home the point that his father had the duality of being a man who was fiercely rebellious yet one who became disgusted if he saw someone not obey basic social niceties.

Where the book suffers, however, is with too much reflection and self-analysis from Juan. We think of the “show versus tell” ethic in writing as applying to fiction, but in this book, Juan would have been better off simply describing the episodes of his life with his father, pointing to his thoughts and emotions that resulted from all these dizzying experiences, then letting the readers imagine the rest. Instead, there are passages where Juan agonizingly inspects his own psyche and heart about being HST’s son, and while probably cathartic for him, it bogs the book down.

All told, this is an eye-opening read that will be of interest to anyone that wants to see into the man behind the Gonzo writings, as the anecdotes Juan tells about his dad are balanced and compelling, and they let us see Hunter S. Thompson in both extreme moments and day-to-day life.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and reviews and articles of/on books, music, and film. His work has appeared in over 20 publications since 2008. His pieces on crime fiction and film have been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Crimeculture, Paperback Parade, Mulholland Books, and Stark House Press. He is a regular contributor to The Life Sentence crime fiction web site, and Shindig! music magazine. Brian lives in Durham, North Carolina. He can be found on Twitter @brianjoebrain.