As a kid I, along with most of the rest of the country, watched the made-for-TV movie Born Innocent. If you don’t know that film, it’s a 1974 title that stars Linda Blair as a once “normal” teenage girl who, mostly due to her parents’ cruel indifference, goes down a path that leads to the hell of life inside a girls’ reform school. At that time I wasn’t familiar with the concept of camp entertainment, or that there were whole subgenres within that realm that had to do with babes behind bars and reform school girls. Born Innocent was just the big TV movie that everybody was talking about that week, and it starred that girl who’d been in The Exorcist, and I wanted to see it.

As a kid I, along with most of the rest of the country, watched the made-for-TV movie Born Innocent. If you don’t know that film, it’s a 1974 title that stars Linda Blair as a once “normal” teenage girl who, mostly due to her parents’ cruel indifference, goes down a path that leads to the hell of life inside a girls’ reform school. At that time I wasn’t familiar with the concept of camp entertainment, or that there were whole subgenres within that realm that had to do with babes behind bars and reform school girls. Born Innocent was just the big TV movie that everybody was talking about that week, and it starred that girl who’d been in The Exorcist, and I wanted to see it.

The movie devastated me. The tale of a likable kid who was emotionally abandoned by her parents and left to fend for herself, with no place or person to turn to for ultimate security, left me shaken. It was so desolate. It made me realize that things like having parents who cared about you, and protection from bullies, were gifts, not to be taken for granted. I hugged my mom extra hard before going to bed after watching the movie.

I re-watched Born Innocent sometime after it was issued on DVD in 2004. By that time I was fully versed in camp entertainment, and I went into the viewing expecting to enjoy the film on that level. I mean, c’mon—Linda Blair, reform school chicks, ’70s clothes and hairstyles . . . press “play movie,” break out the cheese popcorn, and let’s get ready for some giggles. But I didn’t laugh through that sitting, any more than I did when I was younger. I still found the story vastly sad and totally moving. This time my infant daughter got the extra-tight hug.

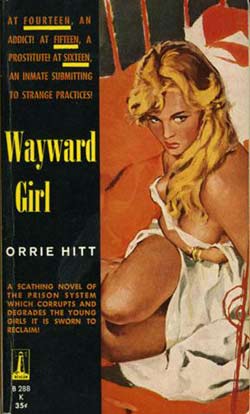

Orrie Hitt’s superb 1960 pulp novel Wayward Girl affects me the same way as Born Innocent. Sure, the book is pure exploitation fodder. You can imagine it being made into a drive-in movie, and you can hear the narrator of the trailer promising you “a no-holds barred, shocking story that reveals the truth about today’s desperate youth. They take drugs their parents haven’t even heard of, their bodies are something they use to get what they need, their schoolbooks remain untouched while they engage in gang fights in the street…”

Yeah, yeah, it’d be an excellent campy movie, right up there with Teenage Gang Debs and all that kind of fare. But really there’s nothing tongue-in-cheek about Hitt’s novel, which, like many of his works, both embraces and transcends the exploitation milieu. Sandy Greening, the “Wayward Girl,” is somebody Linda Blair’s Born Innocent character could have befriended. The two girls might have been able to help each other. Sandy is 16. Her dad’s doing time, sent to the pen when he got nabbed trying to rob a gas station, after being egged on by his wife about all the things their family couldn’t afford on his meager salary. His wife, Sandy’s mom, isn’t exactly pining away for her hubby while he sits in the pokey; she slurps wine around the clock and beds down with the slimeball who pushes dope to Sandy and her crowd. Sandy and her mom had to move to the bad side of the tracks after Sandy’s dad got sent away; but that’s cool with Sandy because, whereas in their old neighborhood it was a stigma to have a con as a parent, where they live now it’s a badge of honor. Sandy, done with school, slings hash at a greasy spoon. But she makes her real money by selling her voluptuous body, for five dollars a pop, to many of that establishment’s woman-hungry male customers. And she needs that extra loot, to support the heroin habit she got saddled with after being turned on to marijuana then to “H” by her mom’s boyfriend and his street dealers.

Sandy’s also part of a mixed-gender gang. The leader of that outfit is the closest thing she has to a steady guy. When her beau fatally knifes a member of a rival gang, the local cops zero in, and as part of their dragnet operations, they set Sandy up to get caught hooking. Off she goes to a reform school. But the fuzz at least do her the favor of sending her to the “good” reform school: the progressive one, where girls are seen for “who they are, not what they have done.” At the school, Sandy is allowed to finish her high school work, she has a job in the library, and if she behaves herself she’s eligible not only for early release but, while she’s still there, weekends on leave where she gets to spend time in the home of a “nice family” willing to help out these troubled girls.

Sound too good to be true? Well, duh. But I’ll let readers unfamiliar with the book learn about the school’s matron, the “nice” family, and all that happens after Sandy leaves the school and goes back on the outside. If you’re like me, you’ll find all of it engaging and fascinating. And you’ll shake your head in disbelief but you won’t laugh. And you’ll want to hug somebody after turning the last page, if not all throughout the read.

Orrie Hitt, “The Shabby Shakespeare,” wrote a head-spinning number of pulp novels. (Look for a “Hall of Famer” career retrospective article on him by me, right here, in the near future.) I’ve been going through his books like they’re candy, the same way he wrote them. Many of them are worthy of inclusion in this series. I’ve chosen to single out Wayward Girl because it’s my personal favorite of all the Hitt titles I’ve read so far (along with Call Me Bad), and because it affects me in the same way as an old movie that left a permanent impression on me when I was young.

Following is an assortment of striking passages from the book. I purposely left out any (and some of these are dazzlers) that give away too much plot:

At first Phil had given her the smokes for nothing but as soon as she had acquired the habit he had asked for money. There had been only one thing to do. She had started picking up men on the street and bringing them up to the room. At the beginning she had charged two dollars for her favors but she’d grown wiser with the passing of time and had boosted her price to five – and ten if she could get it. Soon she had too many men to continue using the room and Tommy had given her a key to the club. A few of the other girls also had keys and they used the back room for the same purpose. There were two cots and more than one night she had made her money on one cot while another girl had been making hers on the other. She had felt no shame, simply a regret that she could not promote more money for her wares.

***

She had nothing in common with her mother. Flora Greening was simply another person with whom Sandy shared the same room.

***

The courtroom was not a big place and Sandy saw her mother was there, sitting to one side and simply staring at Sandy as she entered. Her mother’s eyes looked red, as though she had been on the wine all night long, and it was obvious she had been crying. A tiny sneer pulled at Sandy’s mouth. What was her mother crying for? You took your chances and sometimes the turn of the wheel came against you. What did her old lady expect when you lived on Central Avenue? You gave it away or you sold it. Was there much of a difference?

***

Suddenly, watching the people, Sandy felt sorry for herself, sorry for her father, even sorry for her mother, sorry for everybody who had made a mistake. How had she? But she knew the answer to that one. It had been easy, easier than going to school and enduring the remarks of the kids and making something of herself. In that instant she hated her past life . . . hated everything and everybody that reminded her of what she had been. But mostly she was unhappy with herself because she had been so stupid. She should have stayed away from the grass and the H and she should have made her connections uptown, getting from twenty-five dollars up for a throw instead of from ten dollars down. A guy did the same thing to you for fifty bucks as he did for five. Why sell yourself short?

***

It seemed to her that everybody was trying to change her but there was not much she could do about it. Let them have their fun, let them earn their money, and when she got out she would do as she pleased. To fight against them was only to make matters worse for herself.

Read about more Lost Classics of Noir.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and various things about books, music, and film. His articles on crime fiction books and authors have also been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Crimeculture, Paperback Parade, Black Mask, and Mulholland Books. He lives in Durham, North Carolina, with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, their cat Rita Lee, and too many books and CDs.

Read all posts by Brian Greene for Criminal Element.

Great lead-in with the connection to “Born Innocent”. That was “Must-Watch” TV back-in-the-day. Great article Brian.

OK HW