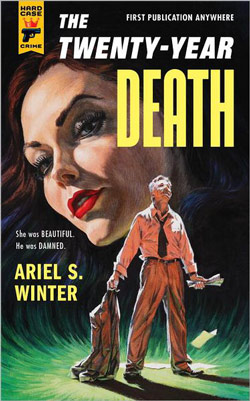

The Twenty-Year Death by Ariel S. Winter (available August 7th) is a single book made up of three crime novels told across decades—from the years 1941, 1951, and 1961—each capturing the style and setting of a giant of crime writing from the era: Georges Simenon, Raymond Chandler, and Jim Thompson.

The Twenty-Year Death by Ariel S. Winter (available August 7th) is a single book made up of three crime novels told across decades—from the years 1941, 1951, and 1961—each capturing the style and setting of a giant of crime writing from the era: Georges Simenon, Raymond Chandler, and Jim Thompson.

The three stories together tell one epic, interlocking tale of an an author whose life is shattered when violence and tragedy consume the people closest to him. In this exclusive excerpt, you’ll get a taste from each of the three!

And don’t miss the special bonus at the end of the excerpt!

MALNIVEAU PRISON

The rain started with no warning. It had been dark for an hour by then, and the night had masked the accumulation of clouds. But once it began, the raindrops fell with such violence that everyone in Verargent felt oppressed.

After forty minutes of constant drumming—it was near eight o’clock, Tuesday, April 4, 1931—the rain eased some, settling into the steady spring rainfall that would continue throughout the night.

The rain’s new tenor allowed for other sounds. The baker, on his way to bed for the night, heard the lapping of a large body of water from behind his basement door. He shot back the lock, and rushed downstairs to find nearly two feet of water covering the basement floor. A gushing stream ran down the wall that faced the street.

Appalled, the baker rushed up the stairs calling to his wife. She hurried past him, down the stairs, to see for herself, as he went to the coat rack to retrieve his black rain slicker. This had happened before. Something blocked the gutter at the side of the street, and the water was redirected down their drive, flooding the basement. Somebody in Town Hall would hear from him in the morning.

He opened the front door and went out into the rain just as his wife arrived from the basement. The force of the storm pressed the hood of his slicker over his forehead. He hurried down the drive with his head bowed; rivulets of water formed long v’s on the packed earth beneath his feet. Now he’d be up much of the night bailing out the basement, and he had to be up at three-thirty to make the bread. The mayor would hear about this in the morning!

He reached the end of the drive, about twenty-five feet, and looked along the curb towards the opening to the sewer. The streetlamps were not lit, but there appeared to be a person lying in the gutter. The baker cursed all drunks.

“Hey!” he called, approaching the man, who was lying face down. The baker’s voice was almost covered by the rain. “Hey, you!” He kicked the man’s foot. There was no response. The street was dark. No one else was out in the storm. The houses across the way and along the street were shuttered. He kicked the man again, cursing him. Water still coursed along the drive towards his house.

His schedule was shot; tomorrow was going to be a nightmare. Then he noticed that the drunk’s face was buried in the water coursing around his body, and the baker felt the first flicker of panic.

He knelt down, soaking his pants leg. The rain felt like pins and needles against his shoulders. Choking back his discomfort, he reached for the drunk’s shoulder, and rolled him away from the curb so that he was lying on his back in the street. The drunk’s head rolled to the side. His eyes were open; his face was bloated. He was undisturbed by the rain.

The baker jerked back. The concrete thought: He’s dead! coincided with a gathering numbness and the uncomfortable beat of his heart in his throat. The baker turned, and hurried back to the house.

His wife, elbows cupped in opposite hands, held herself at the door. “Did you fix it?”

“Call the police,” the baker said.

His wife went to the phone stand at the foot of the stairs. “You’re dripping on the floor; take off your coat.”

“Call the police,” the baker said, not explaining himself. “Call the police, call the police.”

His wife raised the phone to her ear. “The line’s down. It must be the storm.”

The baker turned and grabbed the doorknob.

“Where are you going? The basement…”

“There’s a man dead in the street.”

The baker lived ten minutes from Town Hall, which was also the police station. Nervous, he avoided looking at the dead man as he turned towards the center of town. The rain was still steady, a static hush over everything that served to both cloud and concentrate the baker’s hurried thoughts: A man was dead. The basement was flooded. It was late. A man was dead.

At the police station, he found that it would not have mattered if the phone lines had been operational. Of the three officers on duty, two had been called to assist with an automobile crash before the phone lines had gone down.

“The rain makes the roads treacherous,” the remaining officer explained. “People shouldn’t be out.”

“But the man’s dead,” the baker insisted, confused that these words had not inspired a flurry of activity.

“We just have to wait for Martin and Arnaud to return.”

The baker sat on one of the three wooden chairs that lined the wall between the front door and the counterwhere the officer sat. Small puddles of water refracted on the tile, tracing the steps the baker had taken since entering the police station. The officer had already taken his name and statement, and now was trying to pass the time, but the baker was unable to focus. He was exhausted.

Martin and Arnaud returned twenty minutes later. They were young men, the fronts of their slickers covered in mud from their recent work at the automobile crash. They glanced at the baker, but ignored him, talking to each other, until the officer on duty interrupted them and explained the baker’s situation.

It was decided that Martin would accompany the baker back to his house, while Arnaud would go in the police car to the hospital to retrieve a medic and an ambulance.

Back out in the rain, the men were silent. The streets were still deserted. Even the few late-night cafés and bars at the center of town were closed. Martin and the baker arrived at the baker’s house to find the body unmoved. It was still blocking the gutter, still sending water into the baker’s home. They stood several feet away in silence, their hands in the pockets of their slickers, their shoulders hunched against the rain.

They only had to wait a minute before a police car followed by an ambulance pulled up in front of the house. The medics jumped out of the ambulance and retrieved a stretcher from the back. Arnaud came to where Martin and the baker were standing.

“We will contact you tomorrow, if we need anything else,” Martin said.

The baker watched the medics load the body onto the stretcher and then into the ambulance.

“Somebody needs to fix the drainage,” the baker said, his mind clearing some now that the body had been removed.

“You’ll have to bring that up with the town in the morning.” “I have to be up early, and my basement is flooded.”

The officers were unconcerned.

The baker’s heart wasn’t really in it.

The ambulance pulled away. One of the officers said, “We’ll let you know,” but he didn’t say what they would let him know. They got back into the police car and pulled away, leaving the street once again empty.

The baker could see that the water was already flowing correctly, draining into the sewer. He turned back up his drive, preparing for a night bailing out the basement.

Inside, his wife came downstairs. “What happened?”

The baker peeled off his dripping coat, and began to roll up the sleeves of his shirt. “Some drunk was taken unexpected.”

THE FALLING STAR

Merton Stein Productions was twelve square blocks enclosed by a ten-foot brick wall with pointed granite capstones every three yards. There was a lineup of cars at the main gate that backed out into the westbound passing lane of Cabarello Boulevard. Every five minutes or so the line advanced one car length. If you had urgent business you were no doubt instructed to take one of the other entrances. Since I had been directed to this one, I figured my business wasn’t urgent.

It was just about noon on a clear day in the middle of July that wasn’t too hot if you didn’t mind the roof of your mouth feeling like an emery board. I smoked a cigarette and considered taking down the ragtop on my Packard to let in the mid-day sun. It was a question of whether it would be hotter with it closed or with it open. When it was my turn at the guard stand, I still hadn’t decided.

A skinny young man in a blue security uniform stepped up to my open window without taking his eyes off of the clipboard in his hands. His face had the narrow lean look of a boy who hadn’t yet grown into his manhood. His authority came from playing dress-up, but the costume wasn’t fooling anyone, including himself. “Name,” he said.

“Dennis Foster,” I said. “You need to see proof?”

He looked at me for the first time. “You’re not on the list.”

“I’m here to see Al Knox.”

He looked behind him, then out to the street, and finally settled back on his clipboard. “You’re not on the list,” he said again.

Before he could decide what to make of me, a voice said, “Get out of there.” The kid was pushed aside and suddenly Al Knox was leaning on my door, wearing the same blue uniform, only many sizes larger. There was a metal star pinned to his chest and a patch below it that stated his name and the title Chief of Security. He stuck his hand in my face and I took it as he said, “Dennis. How the hell are you?”

“Covering the rent. How’s the private security business?”

“Better than the public one. Give me a second, I’ll ride in with you.” He backed out of the window, told the skinny kid, “Open the gate, Jerry, this charmer’s with me,” and then crossed in front of my car in the awkward lope his weight forced on him. He opened the passenger door, grunted as he settled himself, and pulled the door shut. The sour smell of perspiration filled the car. He nodded his head and pointed at the windshield. “Just drive up Main Street here.”

Jerry lifted the gate arm and I drove forward onto a two-way drive lined with two-story pink buildings that had open walkways on the second floors. There was a lot of activity on either side of the street, people in suits and people in painters’ smocks and people in cavalry uniforms and women in tight, shiny skirts with lipstick that matched their eyes. Three men in coveralls with perfectly sculpted hair worked bucket-brigade-style unloading costumes from a truck. Workers walked in both directions across a circular drive to the commissary. Knox directed me to the third intersection, which had a street sign that said Madison Avenue. Messrs. Young and Rubicam wouldn’t have recognized the place. We turned left, drove one block over, past a building the size of an airplane hangar, and made another left onto a boulevard with palm trees in planters down the middle of the street. Here there was a four-story building large enough to be a regional high school. It had an oval drive and two flagpoles out front, one flying Old Glory and the other flying a banner with the Merton Stein crest on it. We drove past the oval and pulled into a spot at the corner of the building beside a row of black-and-white golf carts.

In front of us was a door with wired glass in the top half that had the word “Security” painted on it in fancy black-and-gold letters. I suppose the men who lettered all those title cards in the old days needed something to keep them busy now. To make doubly sure we knew where we were, a sign on a metal arm above the door read “Security Office.” Knox started around the car to lead the way when a woman’s voice said something that wasn’t strictly ladylike. We looked, and three cars over a blonde head bobbed into sight and then vanished again.

Knox pulled up his pants at the waistband as though they might finally decide to go over his belly, and went around to where we had seen the woman’s head. I followed. Bent over, arms outstretched, the blonde made a perfect question mark, an effect accentuated by the black sundress she wore, which covered her from a spot just above her breasts to one just above her knees in a single fluid curve. She had on black high-heeled shoes with rhinestone decorative buckles, simple diamond stud earrings and a necklace with five diamonds set in gold across her white chest. In light of the earrings and the necklace, I allowed that the decorative buckles on the shoes might be real diamonds too. What she was bending over was the back seat of a new ’41 Cadillac sedan. A pair of legs in wrinkled trousers was hanging out of the car, the man’s heels touching the asphalt. She said the surprising word again, followed by, “Tommy.”

Knox said, “Do you need any help, Miss Merton?”

She straightened up. There was no sign of embarrassment on the sharp face that came into view, just annoyance and frustration. She brushed her hair back out of her face with one hand, and it stayed exactly where she wanted it, in an alluring sheet that just touched her shoulders. “Oh, Al. Can you help me get Tommy into the car again? He’s passed out and he’s too heavy for me.”

Knox started forward and Miss Merton stepped back out of his way. She looked at me, and a smile formed on her face that suggested we shared a private secret. “Hello,” she said. I didn’t say anything. Her smile deepened. I didn’t like that.

Knox wrestled Tommy’s legs into the back seat, a process that involved some heavy breathing and maybe a few choice words under his breath too. At last he had the feet stowed in the well behind the driver’s seat, and he slammed the door with satisfaction. “There you go, Miss Merton.”

She turned to him, and said in a hard voice, “Tommy can’t expect that I’ll always go around cleaning up after him.”

“No, ma’am,” Knox said.

Miss Merton looked at me, gifted me with another smile, and then pulled open the door and poured herself into the driver’s seat. Knox faced me, shaking his head but not saying anything as the Cadillac’s engine caught and started. Only once the car was out of view did he say, under his breath, “Vera Merton. Daniel Merton’s daughter. She’s always around here getting into some trouble or other. The son doesn’t usually even make it this far. He must have found himself caught out last night.” He rolled his eyes and shook his head again. “The bosses, yeah?”

“The bosses,” I said.

He gave a hearty laugh and slapped me on the back. “I’m telling you. This place is filled with crazies. Come on into my office, I’ll fill you in.“

POLICE AT THE FUNERAL

I sat on the edge of the hotel bed trying to convince myself that I didn’t want a drink. The argument that it had been three months since my last drink—and that had only been one Gin Rickey—and almost seven months since my last drunk wasn’t very convincing. I tried the argument that I would be seeing Joe for the first time in four years, and Frank Palmer, Sr., the lawyer, and probably Great Aunt Alice too, so I should be sober when I saw them. But that was the reason I wanted a drink in the first place.

I glared at the mirror attached to the front of the bathroom door. I knew it was me only out of repeated viewing, but now, about to see my son, I saw just how broken I looked. My hair was brittle, more ash-gray than straw, and my face was lined, with crow’s feet at the corners of my eyes, sunken cheeks, and broken blood vessels across the bridge of my nose. I looked worse than my father did when he died, and he was almost ten years older then than I was now.

“You don’t want a drink,” I said to my reflection. Then I watched as I sighed, exhaling through my nose, and my whole body sagged.

Why the hell was I back in Maryland, I asked myself, back in Calvert City?

But I knew why. It was time to pay Clotilde’s private hospital again. And I owed money to Hank Auger. I owed money to Max Pearson. I owed money to Hub Gilplaine. And those were just the big amounts, the thousands of dollars. There were all kinds of other creditors that wouldn’t be too happy to know I was three thousand miles from S.A. There had to be money for me in Quinn’s will. Otherwise Palmer wouldn’t have called me.

The door from the hall opened in the front room. It crashed shut and Vee appeared in the mirror, framed by the square arch that separated the rooms. “Don’t you just love it?” she said.

She was in a knee-length sable coat with a collar so big it hid her neck. She wasn’t bad to look at normally, deep red hair, un-marked white skin, and what she was missing up top was made up down below. In the fur and heels she looked sumptuous.

“It’s the wrong season for that,” I said.

She came forward. “He’d been saving it.”

“I hope he’s planning to p—to give you more than a fancy coat.”

“He’s paying for the suite.” She opened one side of the coat, holding the other side across her body, hiding herself. But I could see that she wasn’t wearing anything underneath anyway. She slid onto the bed behind me, putting her hands on my shoulders. In the mirror, a line of pale skin cut down her front between the edges of the fur.

“He didn’t wonder why you weren’t staying with him?”

She faked shock, raising a hand to her mouth in the perfect oops pose. “I’m not that kind of girl,” she said, and then she made herself ugly by laughing, and flopped back on the bed, her whole naked body exposed now, her arms outstretched, inviting me to cover her.

“You were just with him,” I said.

“But now I want you. That was just business anyway.”

I shook my head, my back still to her, although I could see her in the mirror.

She dropped her arms. “What’s wrong with you?”

“I want a drink,” I said.

“Then have one.”

“I can’t.”

“Forget what the doctors say.” She was losing her patience. “You’d feel a lot better if you took up drinking again instead of always whining about it. Now come here. I demand you take care of me.”

I looked back at her. She should have been enticing, but she was just vulgar. “I’ve got to go.” I stood up.

“Like hell you have to go,” she said, propping herself up. “You bastard. You can’t leave me like this.”

“The will’s being read at noon. As it is I’ll probably be late. That’s what we’re here for in the first place, remember?”

“You pimp. I’m just here to pay for you. I should have stayed with him upstairs. At least he knows he’s a john, you pimp.”

“If I’m a pimp, what’s that make you?”

“I know what I am, you bastard. You’re the one with delusions of grandeur.”

I could have said, that’s not what she thought when she met me, but what would be the point? I left the room, going for the door.

She yelled after me. “You’ll be lucky if I’m here when you get back.”

I went out into the hall. I should have left for the lawyer’s before she got back. I had heard her go through that routine more times than I could count, but it was the last thing I needed this morning. No matter how much she got, she couldn’t get enough. An old man couldn’t satisfy a woman like that. But when I first met her, I hadn’t felt old. She’d made me feel young again, and I hadn’t realized what she was until later. I wasn’t any pimp, I’ll say that, but a man’s got to eat, and she was the only one of the two of us working.

I took the elevator downstairs to the lobby. Instead of pushing through the revolving doors to the street, I went into the hotel bar. The lights were off since enough sunlight was creeping through the Venetian blinds to strike just the right atmosphere. It took my eyes a moment to adjust. When they had, I saw that I was the only person in the bar other than the bartender, who stood leaning against his counter with his arms crossed looking as though he was angry at the stools. I went up to the bar. “Gin Rickey,” I said.

He pushed himself up, grabbing a glass in the same motion. He made the drink, set it on a paper doily, and stood back as if to see what would happen.

I drank the whole thing in one go. I immediately felt light-headed, but it was a good feeling, as though all of my tension was floating away. I twirled my finger, and said, “Another one.”

The bartender stood for a moment, looking at me.

“Room 514,” I said. If Vee’s “friend” was paying for the room, he could afford a little tab.

The bartender brought my second drink. “Don’t get many early-morning drinkers,” I said, picking up the glass.

“It’s a bad shift,” he said.

“And let me guess. You worked last night too.”

“Until two ayem.”

I tipped my glass to him and took a drink. He watched me like we were in the desert and I was finishing our last canteen. I set the glass down, careful about the paper doily. “If you came into big money, I mean as much money as you can imagine, what would you do with it?”

He twisted his mouth to the side in thought. Then he said, “I’d buy my own bar.”

“But this was enough money so you didn’t have to work again. You could settle down anywhere, or don’t settle down, travel all over.”

“What would I want to leave Calvert for?”

“Get a new start. You said yourself you were miserable.”

“I said it was a bad shift.”

“Aren’t they all bad? Every last one of them.”

He put his big palms down on the bar and leaned his weight on them. “No, they’re not. Are you finished with that? Do you need another?”

I waved him away. “When you’re a kid, you know how you dream you’ll be a college football star or a fighter pilot? How come you never dream of just being satisfied?”

“I like tending bar.”

“Right.” I drained the last of my drink, and felt composed, at least enough for the reading of the will, even with Joe there.

“Kids don’t know anything anyway,” the bartender said. “What do you do, mister?”

“Nothing anymore. I was a writer.”

“Anything I would have heard of?”

“Probably not,” I said.

“You need another?”

I shook my head. I had a soft buzz on, and it felt good. It felt better than it should have. “Put the tip on the tab,” I said. “Whatever you think’s right.”

“Thanks, mister.”

I shrugged. “I just came into some money.”

“Well, thanks.”

I waved away his gratitude. It was making me feel sick.

I walked out of the bar and pushed my way through the revolving door in the lobby onto Chase Street. The August heat and humidity had me sweating before I got to George and turned south towards downtown. Calvert hadn’t changed much since Quinn and I lived here in 1920. Or was it ’21? The Calvert City Bank Building over on Bright Street that now dominated the skyline hadn’t been there, and there had been more streetcars instead of busses, but overall the short and stocky buildings of the business district were the same. I remembered when those buildings had seemed tall, after Encolpius was published and I suddenly had enough money to marry Quinn. Now Quinn was dead and Encolpius and all my other books were out of print and even Hollywood had thrown me out and my life would never be as good as that day here in Calvert thirty years ago.

I was one poor bastard. If I had known how much of our married life was going to be screaming at each other and trying to outdo the other with lover after lover, pill after pill, drink after drink, I would have—at least I hope…yeah, I would have called it off. Quinn knew how to make me jealous from across the room. It was only natural when I started stepping out. And there were the two miscarriages and then Quinn started bringing a bottle to bed and finishing it in the morning, so of course I did the same. It got to the point where I couldn’t think without something to get me going. We tried the cure, once in New Mexico, once in upstate New York, but it didn’t last long, and when we got to Paris, we didn’t care anymore, it was all-out war.

Copyright © 2012 by Ariel S. Winter.

You’ve read the excerpt now CLICK HERE TO ENTER FOR A CHANCE TO WIN a copy!

A long-time bookseller at The Corner Bookstore in New York City and Borders in Baltimore, Ariel S. Winter is also the author of the forthcoming children’s picture book One of a Kind (Aladdin) and of the blog We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie, devoted to the rediscovery of long-forgotten children’s books written by literary icons such as John Updike, Langston Hughes, and Gertrude Stein. His writing has appeared in The Urbanite and on McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, and in 2008 he won the Free Press ”Who Can Save Us Now?” short story contest. He lives in Baltimore, Maryland.