Before tapping out novels on the keyboard, my working hours were spent in various assignments as a police officer and, prior to that, as a fire department paramedic. Those two former careers certainly bolster the third. Countless memories of people at their worst and best drift through my mind.

In extreme situations—the kind of turning point that novel or movie plots hinge on, or the events in which cops are called to intervene in dozens of times per day—a choice is present.

I’m fascinated by people, the choices they make, and the fly-by moments when those decisions are made. Choices are tests. Often, people don’t view those moments in which they made a choice as pivotal, but that lack of recognition doesn’t diminish how key the choice and the moment are. I chose to become a sergeant.

A sergeant does the extra difficult things, such as take full responsibility for the scene, discipline an officer who went too far, tell a citizen the officer made no foul, or knock on a doorway in the middle of the night to deliver a death notification.

Sometimes I didn’t travel to do those notifications, I intercepted.

Two brothers, around ten and eleven years old, were trusted to stay home for just an hour or so without an adult around. They’d passed this test many times. What the parents didn’t know was that the boys had figured out the combination to their father’s briefcase. They knew this was where he locked up his pistol. They also knew where the ammo was and how to load the gun. Many times, they played with this forbidden grail, always putting it away just in time, right before the adults came home.

They kept their daring secret until the lone survivor explained it all to me.

That night, as they were alone and again playing their finite game, it ended in the tragic way readers will have guessed. One boy called 911 to beg for help because he’d accidentally shot his brother in the chest with a large caliber handgun.

The first responders, strangers to this boy, were all tested.

The walls were streaked with red because the shooter held his lifeless brother, got covered in blood, and wailed about the house before going for the phone and, eventually, the door to let us in.

We do what we do: make the scene safe, get to the victim fast, and secure the weapon. One officer is shooting photographs within minutes. But the paramedics and firefighter stand down. This makes the boy ask the obvious.

“Why aren’t you helping him?”

My officers, the paramedics, and the firefighters looked away from his teary face. It fell to me, the sergeant on scene, to tell the little guy that we could not help his brother.

The survivor’s pain erupted in screams and a physical collapse. It gutted us, but headlights approached, so I left him in the care of my colleagues. I had to intercept the returning adult.

Put yourself in that car. Jump out and rush for your front door the way adults will if they’ve left younger children alone then, upon returning home, find every emergency vehicle imaginable. A police squad car, a supervisor’s patrol vehicle, an ambulance, and a fire engine are blocking your driveway.

I remember a mom and a grown sister charging the front door.

Now, the test has come due for the adults in the family.

I stopped both women and made them listen to me before going inside. I told them the boys played with their father’s gun and one was dead, the other—let’s call him Toby—was inside and just learned that it’s final. We could not help the dead boy.

The adult sister asked me who was alive.

“Toby.”

Her face crumpled in horrified, aching sympathy. “Poor Toby.”

She passed the test. It was all about Toby now, how to recover from this awful mess.

Before I was a street sergeant, I worked in the Crimes Against Children Unit. This grisly specialty squicks out most cops to the point that they avoid assignment to the CAC unit. I’ve chatted with children who were obviously threatened not to reveal a sinister secret to me or any other adult. The burden of such an ugly compromise—and the post-traumatic stress on these youngsters who are made to protect an adult—is staggering.

The diverse ways that adults in these children’s lives respond to the affected little one is amazing. Some parents don’t notice the crumbling psyche, others go all in, as far as it takes to uncover and heal the trauma.

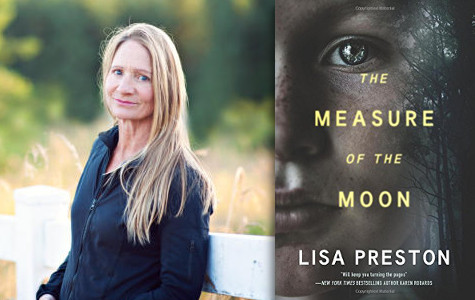

In writing The Measure of the Moon, I wanted to create a parallel novel exploring the world of traumatized children from the viewpoint of the child, the adult, and the elderly, from traumas both acute—it happened last night—to chronic. It happened when the child was five. Or, it happened during World War II.

Defining moments carved in my writer’s soul find their way to the page. Readers familiar with Orchids and Stone know that I delve into questions about what it would take to motivate a person to help a stranger and whether life poses questions that cannot be answered? (A lot, and yes.) Moon tackles similar questions from new angles. Sometimes a fresh look offers new resolutions, fortitude and hope.

Read an excerpt from The Measure of the Moon!

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Lisa Preston is the author of Orchids and Stone as well as several nonfiction books on animal care. Her experiences as a mountain climber, fire-department paramedic, and police sergeant are channeled into fiction that is suspenseful, fast paced, and well acquainted with human drama. She has lived in Arizona, California, and Alaska and now makes her home in western Washington.