An attractive young woman smiles at a man through her apartment window. Once he’s in her apartment, she embraces him.

“How are you going to kill me this time?” she asks.

“I’m going to slash your throat,” he answers.

Soon afterwards, we see them in bed, the man out of frame, the woman atop the man, shot from behind so we see her bare back, and when she emits a little gasp, for a second, we don’t know what it means.

Is she feeling genuine pleasure from their sexual act, or is she pretending to be hurt, killed, from what must be their regular erotic ritual?

Already, a minute or two into the story, the viewer is in unsettling, ambiguous territory, and as things proceed, the viewer will come to find that this is a film that keeps you off balance for its entire two-hour running time.

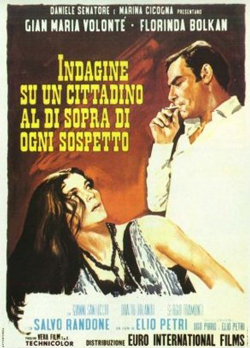

Elio Petri’s Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion was released in Italy in 1970. Petri was 41 at the time, and Investigation was his 7th feature. Once a member of the Communist Party, politically engaged even after he left the Party, Petri felt it his duty to reach a large audience and had no qualms about using commercial genres to achieve this end.

Elio Petri’s Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion was released in Italy in 1970. Petri was 41 at the time, and Investigation was his 7th feature. Once a member of the Communist Party, politically engaged even after he left the Party, Petri felt it his duty to reach a large audience and had no qualms about using commercial genres to achieve this end.

In 1965, he had made the satirical 21st-century science fiction drama, The 10th Victim, starring Marcello Mastroianni and Ursula Andress—a film known now for its Pop Art decor and visual stylings—and in 1968, he’d done the disturbing psychological horror film A Quiet Place in the Country, with Franco Nero and Vanessa Redgrave. Within its genre trappings, The 10th Victim tackled themes such as commercialism and spectacle in capitalistic society—its depiction of a television show where people hunt other people foreshadows reality TV by decades—and A Quiet Place in the Country looked at how outmoded the romantic, solitary artist is in a world that views art as a commodity. For his next film, Investigation, Petri set the story in contemporary, urban Italy, crafting a narrative that examines authority, power, and corruption. He used the crime genre this time, centering his tale around a murder and its aftermath.

The film takes the form of an inverted detective story. That opening scene where the woman gasps in bed is indeed her death scene. The man has slashed her throat with a small razor.

The man then washes her blood off in the shower, takes a nap, gets dressed, and sets about re-arranging the scene—leaving, for example, a light blue fiber from his tie under her fingernail. He takes jewelry out of her dresser and pockets it, though he leaves a wad of cash behind.

We’re not sure what his motivation is for planting clues, but he does everything with a resolute calm. The man seems to know what he’s doing.

Finally, before leaving her apartment, he uses her phone to call the police and report a crime, giving the officer he’s talking to the apartment address and the victim’s name, Augusta Terzi.

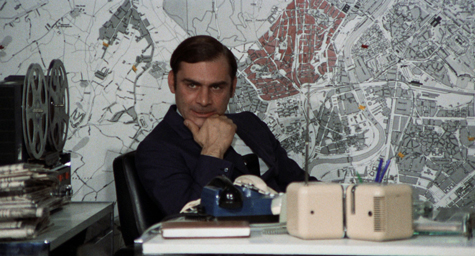

How surprised we are to find, moments later, after the man has driven to work, that his place of employment is a police station and that, in fact, he is the homicide division chief with the metropolitan police force. An underling informs him of the anonymous call they received about a crime at an Augusta Terzi’s apartment, and he tells his subordinate to get over to the scene. His subordinate goes, and the rest of the film will alternate between showing the relationship the inspector had with Augusta Terzi and following him as he does his job during the investigation into the crime he committed.

Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion was made during a period in Italy called The Years of Lead. Social conflict and political violence marked these years, which began in the late ‘60s and ran well into the ‘80s. When Petri shot his film in 1969, student protests and labor strikes were common, as were demonstrations led by Marxists and other militant leftists. The unrest often prompted police retaliation, and clashes between leftists and police were frequent.

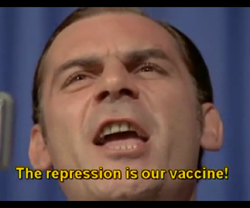

Early in Investigation, we learn that our murderer-police inspector has been promoted out of homicide and made chief of the force’s political division, and on his first day in his new job, he gives a speech that reveals where he stands in regard to dealing with the country’s turmoil. Addressing a room full of police, he explains why the bosses promoted him—why he, in particular, is the right man for the job at this time.

“Memorize this rule,” he says, and tells everyone that inside every criminal, a subversive may be in hiding, and inside every subversive, a criminal may be in hiding. In a way that would please any fascist—and that the Italian audience would have recognized as sounding Mussolini-like—he conflates regular crimes with political crimes, drawing little distinction between ordinary bank robbers and subversives intent on bringing down the state.

He declares that the police, upholders of the law, are defending something that should be immutable, carved in stone. If repression is what is needed to uphold the law and keep society from becoming sick, then repression is their duty. “Repression is our vaccine,” he concludes. “Repression is civilization”

He declares that the police, upholders of the law, are defending something that should be immutable, carved in stone. If repression is what is needed to uphold the law and keep society from becoming sick, then repression is their duty. “Repression is our vaccine,” he concludes. “Repression is civilization”

Ironic, to say the least, that a murderer is mouthing these sentiments, and for the Italian public, it was something of a shock to see Gian Maria Volonte in this role. Volonte was an actor involved with many political causes, and his views were decidedly leftist. He saw eye to eye with Elio Petri in this area, and the two formed a compelling team.

Before Investigation, Petri had cast Volonte in his Sicilian-set adaptation of a Leonardo Sciascia novel, We Still Kill the Old Way (1967), and after Investigation, Volonte would appear in Petri’s The Working Class Goes to Heaven (1971) and his political drama Todo Modo (1976), also adapted from a Sciascia novel, where Volonte plays a character based on Italian prime minister Aldo Moro, later kidnapped by terrorists and murdered.

Throughout his career, from the 60’s to his death in 1993, Volonte starred in movies that grappled with the social and political tumult of the 20th century, and he could play underdogs, commanding figures, or introspective human beings. He played Vanzetti in Sacco and Vanzetti (1971), Lucky Luciano in the 1973 film of that name, and in The Mattei Affair (1972), he was Enrico Mattei, the founder of the Italian petroleum business after World War II.

In the United States, he was best known for his roles in two Sergio Leone westerns, A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For a Few Dollars More (1965)—his humorous histrionics play well against Clint Eastwood’s stoicism—and he’s still best known in this country for those parts. But in Italy, during his long career, he was a huge star, and when Investigation came out, the public appreciated seeing him play a character entirely unlike himself. In thought and deed, the inspector represents the authoritative traits Volonte detested. Yet, he is completely convincing as this man, in no small part because the inspector is a wonderfully complicated character, all strength and resolve on the outside but conflicted within.

Or is conflicted too kind a word for him? Schizoid may be more accurate. The inspector, who remains unnamed through the movie, does not seem to be sure that he wants to get away with his crime. Though busy in his new duties as head of the political division, he keeps an eye on the investigation into Augusta Terzi’s murder, and though he does assist the homicide division at times, helping to interrogate suspects, he also goes out of his way to get the detectives to see that he’s the culprit.

Would they ever believe that their former boss is the killer? How much evidence would it take for them to grasp the fact that he did it? If they could arrest him, yes him, a man above suspicion, they would prove they are the great and merciless force that he so firmly believes is necessary for a strong state.

At one point, irritated by their lack of progress, he goes up to a man in the street and says, point blank, that he is the person who killed Augusta Terzi. He tells the man to memorize his features, go to the police, and give them a complete description of him. The man does, but when the two of them run into each other at the station, the man, comprehending that he’s on the force, becomes so flustered and scared—he cannot believe that the inspector is the same man who called himself a murderer, just earlier, in the street.

Absurdity mixes with suspense, satire with realism, somberness with dark humor. The film gives us a piercing character study, as well as an unblinking look at the workings of a harsh and monstrous system.

People always seem to be walking down narrow hallways and pushing into crowded rooms, creating a sense of claustrophobia. The police station itself is underground, adding to the airlessness, the sense of oppression, and people—the inspector especially—comport themselves as if giving a performance.

Something of a chameleon, the inspector behaves with hardness, modesty, arrogance, or magnanimousness, depending on the situation he’s in. Faced with people of varying rank and station in life, he changes his demeanor quite a bit.

His entire relationship with Augusta Terzi, we learn, was based on performance; the flashbacks reveal the sadomasochistic games they played, with he the dominant one and she the willing submissive, until, one day, she reverses the roles and ridicules his manhood. Stung by her criticisms, he falls apart like a little boy.

The movie also had a prophetic side. About halfway through the film, a bomb explodes in the police headquarters, setting off a massive police roundup of students and left wing militants. Police trucks bring hundreds of these youths to the station, where they shout insults at the police, each other, society in general. It’s a scene of near chaos, and the police mistreat any number of the militants, convinced someone among them is behind the terrorism striking against the state.

In real life, on December 12, 1969, while the movie was being shot, a terrorist attack actually occurred when a bomb went off at the National Agrarian Bank Headquarters in the Piazza Fontana in Milan. Seventeen people were killed, 88 wounded. The police attributed the bombing to leftists and arrested over 80 people. An anarchist suspect under arrest died in police custody after allegedly jumping from the fourth-floor window of the police station. Police claims that he had committed suicide were filled with inconsistencies, but an inquiry exonerated the officers involved. In time, all leftists and anarchists were cleared however, and investigators blamed the explosion on members of a Neo-fascist organization. The right wing group’s motivation: to pin the blame for the bombings on leftists so that the state would crack down on the left and the public would be tricked into believing a communist insurrection was happening.

In real life, on December 12, 1969, while the movie was being shot, a terrorist attack actually occurred when a bomb went off at the National Agrarian Bank Headquarters in the Piazza Fontana in Milan. Seventeen people were killed, 88 wounded. The police attributed the bombing to leftists and arrested over 80 people. An anarchist suspect under arrest died in police custody after allegedly jumping from the fourth-floor window of the police station. Police claims that he had committed suicide were filled with inconsistencies, but an inquiry exonerated the officers involved. In time, all leftists and anarchists were cleared however, and investigators blamed the explosion on members of a Neo-fascist organization. The right wing group’s motivation: to pin the blame for the bombings on leftists so that the state would crack down on the left and the public would be tricked into believing a communist insurrection was happening.

Elio Petri captured this exact societal dynamic in his film. When it opened in February 1970, with Italy tense and the investigation into the Piazza Fontana bombing in full swing, he feared that Italian authorities would ban the film. The public also thought the government would quickly yank it from theaters.

For its opening night showings in Rome, there were long lines. Advanced word on the film was good, and people wanted to make sure they saw it before it disappeared. As it happened, the government did not ban the film, and it went on to be a domestic and international success. Petri garnered praise everywhere, as did Volante, Florinda Balkan—who plays Augusta Terzi—and the inimitable Ennio Morricone, whose score is at once jarring and antic, like the music to a blackly comic circus. It perfectly captures the film’s Kafkaesque quality.

Winner of the Grand Prize at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival, the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America for Best Mystery Screenplay, Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion is Elio Petri’s best work in a career filled with excellent films. Among films that critique the police and abuses of police power, it ranks among the very best ever made. It’s rare to find a film that blends a suspenseful crime story so well with its political concerns. Prescient when it was made, it has aged superbly.

Not only is the inspector nameless throughout the story, but the city portrayed is never specified as Rome or any specific metropolis. In its broadest terms, as a study of corruption and the authoritarian impulse, as a look at the bleak absurdities inherent in bureaucracy, this is a story that could take place anytime, anywhere, and if you have any doubts about that after watching the movie, all you have to do is go online and read the news.

Scott Adlerberg lives in New York City. He co-hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series each summer at the HBO Bryant Park Summer Film Festival in Manhattan. He blogs about books, movies, and writing at Scott Adlerberg’s Mysterious Island. His most recent book is the genre-blending noir\fantasy novella Jungle Horses, available from Broken River Books.

Read all of Scott Adlerberg's posts for Criminal Element!