And I don’t think I was the only one who felt this way. The merchandise, toys, comics, board games, posters, buttons, not to mention a whole section of Disneyland. People connected with this movie. But in one way, maybe I took my obsession a little further. Because how many kids knew that Roger Rabbit was based on a book? Not only did I know, I actually read it. Not the Golden Books novelization of the movie, but the original novel. Yes, at eight, I dug up the source material.

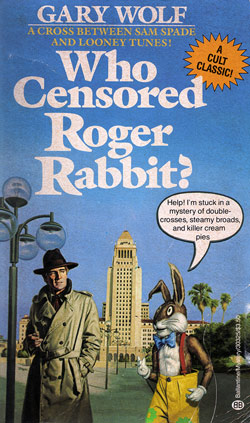

First, a refresher on the movie. Who Framed Roger Rabbit? is a 1940s-style, film noir private detective mystery. P.I. Eddie Valiant is hired by Maroon Cartoons to get incriminating photographs of nightclub vamp Jessica Rabbit in order to get her husband, cartoon star Roger Rabbit, to focus on his work as a cartoon star. That’s right, as a cartoon star, because in this Hollywood, Roger, Jessica, not to mention Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny, and both Daffy and Donald Duck and company are all real, living beings. Valiant finds Jessica playing patty-cake with Marvin Acme (actual patty-cake, no euphemisms here), and when Roger sees the photos, he’s devastated. Marvin Acme turns up dead, Roger’s the number one suspect, and he drags Eddie back into the case to clear his name. Marvin Acme owned Toon Town, a ’toon-only world, and the true motive for his murder hinges on who will inherit the property if his missing will resurfaces. A noir mystery and living, breathing cartoons, what’s not to love?

In Who Censored Roger Rabbit? the ’toons are comic strip characters, not animated cartoons. Jessica Rabbit is shown shooting a television commercial, but otherwise the ’toons are doing newspaper work and comic books. In the first half of the 20th century, in particular in the 1930s and ’40s, comic strip characters were major celebrities, and their creators made fortunes. The comics syndicates truly were like Hollywood studios and their employees stars, so historically, it feels natural for the players in the novel to be involved in the comic strip business, despite some distracting anachronisms—Spider-man is mentioned, but his first appearance wasn’t until 1962, reference is made to Little Orphan Annie hitting it big on Broadway, which didn’t happen until 1977, and television, of course.

One of the nice touches that using comic strip characters allows is that the ’toon characters spout word balloons when they talk. The balloons hover in the air above them, flowery when talking of love, tiny when whispering, blurred when moving too fast. They dissolve or pop after a few moments, leaving white dust on many ’toons’ shoulders that ignorant humans mistake for dandruff. Some ’toons, like Jessica Rabbit, suppress their word balloons in order to better pass as human, but at other times it seems as though Roger isn’t even vocalizing, and Eddie has to read his words to know what he’s saying.

As for passing as human, ’toon racism is rampant in Who Censored Roger Rabbit? There are human-only and ’toon-only eating establishments. Separate elevators. A human police force and a ’toon police force. The comic strip photographer Carol Masters (remember, strips are photographed, not drawn) “lived in a partially ’toon, partially human neighborhood that real estate agents called ethnically enriched, and urban renewers called blighted.” Even within the ’toon community, there are finer shades of racism, with humanoids more desirable than “barnyards.” That a humanoid like Jessica would marry a barnyard like Roger confounds everyone, including Roger. She ordinarily uses her talents to secure human companions. While the movie’s Eddie Valiant won’t work for ’toons because of his personal history, the book’s Eddie Valiant wonders how he could have sunk so low.

So, the plot: Roger Rabbit hires Eddie Valiant to find out why the DeGreasy brothers, owners of the comic syndicate to which Roger Rabbit is under contract, won’t either star him in his own strip as promised or deal him away to parties interested in doing so. Valiant doesn’t think it’s much of a job, but he needs the money so he goes through the motions just to earn his pay. It soon comes out that Roger’s gorgeous wife Jessica has just left him, and moved in with Rocco DeGreasy, and that Roger has been seen making death threats at DeGreasy. When DeGreasy is murdered, Roger becomes the prime suspect only to be murdered himself within hours.

Valiant, made to feel guilty by comic strip photographer Carol Masters, decides to stay on the case, clear Roger’s name, and nab his killer. He’s soon joined by none other than Roger. ’Toons have the ability to create duplicates of themselves, doppels, that do the dangerous stunt work and then disintegrate after an hour or two. Roger’s doppel is far more advanced than that, retaining all of Roger’s memories, and with a lifespan of two whole days. As Valiant (and to some degree Roger) work, people keep asking Eddie if he knows what happened to Roger’s teakettle. Everyone has a different story about the teakettle, and they’re all willing to pay anything for it. But Roger has no idea why.

At the same time, Valiant stumbles across what seems to be a related art counterfeiting scam—original comic strip film negatives and prints are worth substantial sums of money. Rocco DeGreasy’s son runs the DeGreasy art gallery from which originals of Carol Masters’s Roger Rabbit shoots have been stolen. The prints are resurfacing on the illicit art market, and Rocco had them in his possession at his death. Somehow, ’toon pornographer Sid Sleaze is tied in to things, and Jessica once posed for one of Sleaze’s books.

But I have to credit the book as much as the movie in my development as a writer. I read it on vacation with my parents at the Delaware shore in the same week that I read F is for Fugitive by Sue Grafton. These two books were my first foray into adult mysteries, and they made a mystery fan out of me.

But even further, Roger made a noir fan out of me. It wasn’t until high school that I discovered the great noir classics, and again, it was through the movies before the books. The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep, Double Indemnity—Who Framed Roger Rabbit? conditioned me to love these movies. And Who Censored Roger Rabbit? conditioned me to seek out the source material, and read, read, read.

It is often said that the impulse to write comes from a desire to emulate the books you love. In my case, I wore my influences on my sleeve. My novel The Twenty-Year Death is an homage to noir, a trio of pastiches in the styles of Georges Simenon, Raymond Chandler, and Jim Thompson. And I have talked a lot about those three masters while doing publicity for the book. But as interviewers asked over and over, what drew me to noir in the first place, it has been clearer and clearer that the answer is Roger Rabbit.

A long-time bookseller at The Corner Bookstore in New York City and Borders in Baltimore, Ariel S. Winter is also the author of the forthcoming children’s picture book One of a Kind (Aladdin) and of the blog We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie, devoted to the rediscovery of long-forgotten children’s books written by literary icons such as John Updike, Langston Hughes, and Gertrude Stein. His writing has appeared in The Urbanite and on McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, and in 2008 he won the Free Press “Who Can Save Us Now?” short story contest. He lives in Baltimore, Maryland.

This is a great article. It’s been many years since I’ve watched the movie and you really made me want to see it again.