Why read Agatha Christie murder mysteries today?

Christie remains one of the most read authors of all time, but this is the question that struck me when I read Joan Acocella’s essay “Queen of Crime” in The New Yorker.

Acocella suggests that one of the pleasures of Christie’s books is “her portrait of the times: the period between the two world wars, and, above all, the changes that took place after the second war.” She continues:

“Her people are upper middle class or, sometimes, upper class. They gaze with astonished disgust at housing developments and supermarkets. They complain bitterly about how heavily they are taxed and how they can no longer afford to maintain the grand houses they saw as their birthright. Eventually, they sell these huge piles to the nouveaux riches.”

In her re-reading of the long list of murder mysteries that Christie produced over several decades until her death in 1976, Acocella makes a compelling point about the way that Christie’s detective stories create a world of people who look with dismay at all that is modern, all that is changing.

The detective story formula that Christie perfected, and that has shaped the genre every since, has at its center a need for order in a world of moral corruption, irrationality, and a disillusion with the current plans for the future. There is a comfort in getting through one of Christie’s novels, particularly the series of Miss Marple murder mysteries, where the kindly and acutely rational Miss Jane Marple of the village of St. Mary Mead finds immorality at ever turn—and is not surprised.

But much of Acocella’s essay left me wondering if Christie’s murder mysteries give us more than a window on the English past and the pleasure of a well-crafted murder story.

I wonder if it's time to learn now, in our present moment of social change, when old systems seem older than usual, and when the disorder feels more disorderly, from Christie’s well-hewn stories and chaotic writing practices.

Not only are her books about supposedly proper folks who gather in dark-paneled drawing rooms, and about English class structures as firmly rooted as the stone foundations of the manor houses where bloody bodies are found, they are also about a social order that was quickly changing. All that seemed familiar and known was put into doubt and disarray, and every murder was about much more than a corpse in the library.

Which had me asking, what, if anything, might her novels show us about our own time?

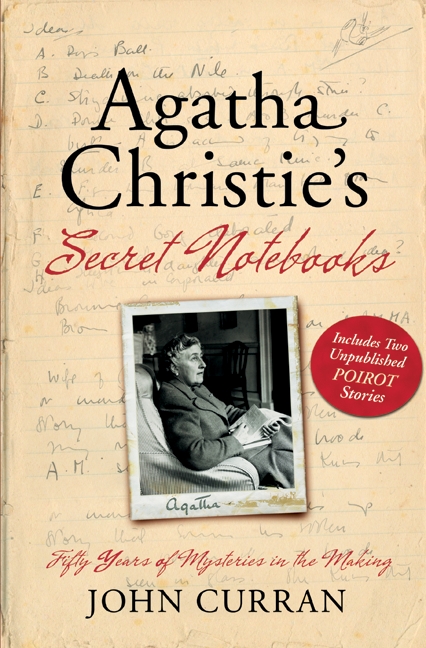

Images courtesy of Tea with Mary Kate and AgathaChristie.com.

James Polchin can be found Writing in Public.