Who Actually Killed Robert Kennedy?

By William Klaber

June 21, 2018

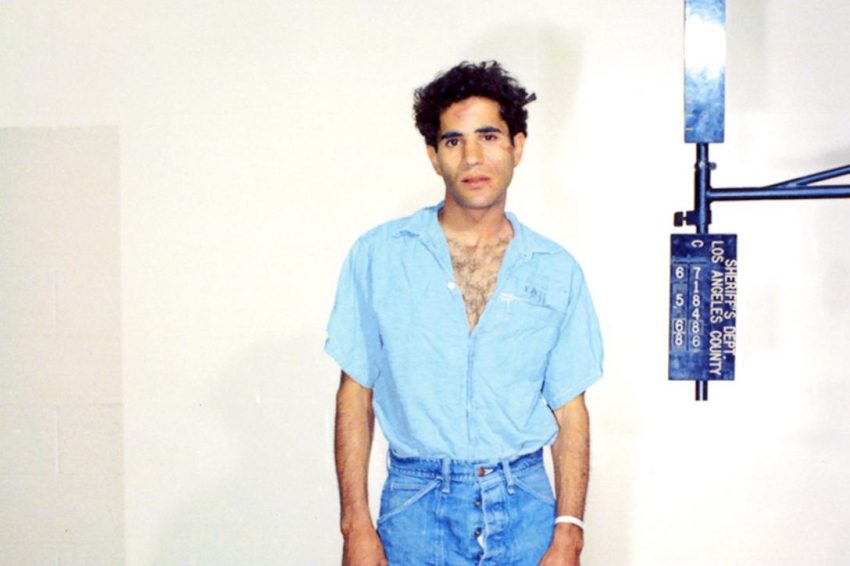

When I first visited the convicted murderer of Senator Robert Kennedy, I was struck by how ordinary he seemed. At that time, in his mid-40s, Sirhan B. Sirhan was kind of like everybody’s kid brother. He was mild-mannered and well-spoken, and unlike most prisoners, he didn’t have a TV in his cell. Instead, he read books and listened to NPR on the radio.

But there was something else, something that made him different from almost any other prisoner—not just in California, any other prisoner anywhere. He had spent his entire adult life in prison for a crime he doesn’t remember. Now, 98% of people reading these words will not believe this—it’s the natural reaction. But as someone who has listened to the tapes of his murder-night interrogations, his jailcell interviews with his attorneys and psychiatrists, and his very strange sessions under hypnosis, I am convinced he is telling the truth. But what could it mean?

What makes the Sirhan case such a puzzle is that, on its face, it could hardly be more open and shut. Robert Kennedy is murdered; Sirhan is captured a few feet away firing a gun. Over time, the prisoner admits to the crime, offers a motive, and says he acted alone.

Finally, a political assassination where there aren’t scary, unanswered questions.

But here’s where it starts to get weird. After Sirhan’s trial—where he is convicted and sentenced to death (commuted to life)—the LAPD decides that all their files on the case are to remain secret. Indefinitely. Why? The police are public servants; the files don’t belong to them. And their flimsy excuse—that they have to protect “confidential sources”—makes no sense. If Sirhan, acting alone, killed Robert Kennedy, who has to be protected?

Then, bit by bit, all through the 1970s, photographs and witness accounts began to emerge—items that were in sharp contrast to the official version of the crime. Calls for the police to open their files increased. But they wouldn’t, and the excuses got more inane. Maybe there were men staying at the Ambassador Hotel that night with women who were not their wives. Didn’t they deserve their privacy? I’m not making this up. Finally, the police were forced to open their files. But that was in 1988, two full decades after the murder.

After the files were opened, a group of researchers—led by Kennedy’s friend Paul Schrade—came together to examine the thousands of documents and hundreds of audio tapes in the newly opened files. This is where I came in. Hearing about what they were up to, I flew west and joined the group. I was there in time to help in the preparation of a formal petition to the LA County Grand Jury to ask them to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate the LAPD for “willful and corrupt misconduct” in its investigation of the murder of Robert Kennedy. Did the petition come with evidence? It did—800 pages of exhibits detailing police “fabrication of evidence, destruction of evidence, and coercion of witnesses.” Using their own files, we had proved that the police had committed serious crimes. But the Grand Jury did nothing.

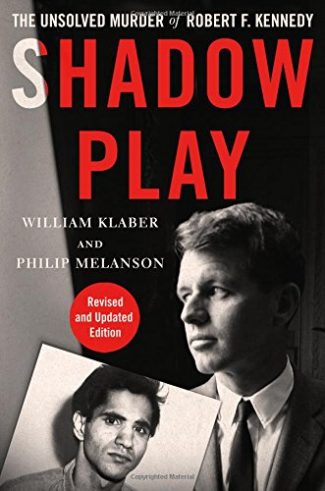

One member of the researcher group was Professor Philip Melanson of UMass, now deceased. He had a quick mind and knew more about the case than I did. When the Grand Jury refused to act, we realized that the evidence would have to brought forth another way. The two of us got to talking one day, and we decided, on faith, to write a book together. Two years later, St. Martin’s Press brought forth Shadow Play, an unapologetic look at a very strange case—a whodunit for smart people.

One member of the researcher group was Professor Philip Melanson of UMass, now deceased. He had a quick mind and knew more about the case than I did. When the Grand Jury refused to act, we realized that the evidence would have to brought forth another way. The two of us got to talking one day, and we decided, on faith, to write a book together. Two years later, St. Martin’s Press brought forth Shadow Play, an unapologetic look at a very strange case—a whodunit for smart people.

Read an excerpt from Shadow Play!

But even smart people might be thinking, I don’t care if Sirhan doesn’t remember. What difference does it make? But what if you knew that evidence in police possession proved to a virtual certainty that a second gun was firing in the pantry that night? And that the police secretly destroyed this evidence? What if you found out that several dozen people reported seeing Sirhan in the company of two other persons and that the police hid these accounts and forced the most prominent of these witnesses to change their stories? What if, after examining the evidence, you concluded that it is very unlikely that any of the bullets from Sirhan’s gun ever struck Robert Kennedy? Now, what might be the meaning of Sirhan’s blank mind?

Does that sound over the top? More fit for the movies? Well, consider that Paul Schrade, a man who was struck in the head by a bullet most surely fired from Sirhan’s gun, went to his last parole hearing at age 92 and said that he thought that none of the bullets from Sirhan’s gun ever struck Robert Kennedy. And just this last December, Robert Kennedy Jr., the son of the late senator, sat down with Sirhan in prison and came out saying that he wanted a new investigation. Schrade and Kennedy are intelligent men, and they have more reasons than you or I to want a truthful account of what happened that night in 1968. Neither man believes that Sirhan was there under his own volition. They have looked at the evidence, and when you look at the evidence, the official version of the crime crumbles. Something else is going on.