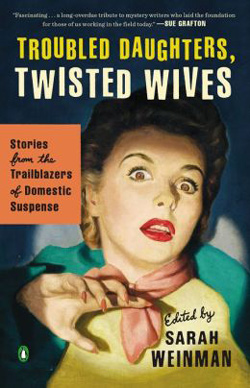

Fourteen chilling tales from the pioneering women who created the domestic suspense genre

Murderous wives, deranged husbands, deceitful children, and vengeful friends. Few know these characters—and their creators—better than Sarah Weinman. One of today’s preeminent authorities on crime fiction, Weinman asks: Where would bestselling authors like Gillian Flynn, Sue Grafton, or Tana French be without the women writers who came before them?

In Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives, Weinman brings together fourteen hair-raising tales by women who—from the 1940s through the mid-1970s—took a scalpel to contemporary society and sliced away to reveal its dark essence. Lovers of crime fiction from any era will welcome this deliciously dark tribute to a largely forgotten generation of women writers.

“Mortmain” by Miriam Allen deFord

“I’ll be back on Thursday, Miss Hendricks, and I’ll drop in here in the afternoon. It’s only three days, and I don’t anticipate any change. You know what to do. If anything happens, you can call Dr. Roberts; he knows all about the case. I wouldn’t go away, with Marsden like this, but — well, it’s my only daughter, you know, and she’ll never be married again — at least, I hope not! — and she’d be heartbroken if her old dad weren’t there to give her away.”

Dr. Staples turned to his patient.

“Good-bye, old man; I’m leaving you in Miss Hendricks’ charge till Thursday. You won’t be sorry to have three days free of me, eh?”

Dr. Staples put on his gloves and picked up his hat from the table by the bed. The sick man nodded feebly, essaying a slight courteous smile. The nurse nodded too, her eyes downcast. She was afraid to look at the doctor — afraid to let him see the incredulous joy in her face.

“So long, then.” He was gone, shutting the door quietly after him.

What unbelievable luck! Cora Hendricks felt herself trembling with excitement. How she had schemed and planned — and it had never occurred to her that anything would keep Staples from his daily visits to his patient. Now she had three whole days and nights.

Today. It was only three o’clock. She could do it today. His four o’clock medicine. By five she would be finished here; by six she could be on a train. By Thursday she could be where Staples would never find her. No — that was foolish. She mustn’t disappear. She would phone Dr. Roberts, and he would come. Perhaps he would summon Staples back, perhaps he would take the whole responsibility. Either way, it would make no di?erence to her. Afterwards, she could go, and then — then her new life would begin.

She sat silently by Marsden’s bed, on the other side of the table, and let her eyes, that she had not dared to let the doctor see, rove around the big room. Back of the framed photograph of Marsden’s dead wife was a sliding panel that hid a safe. She knew the combination; Marsden had given it to her when he wanted her to bring him the insurance papers for the doctor to look at. Marsden knew he was going to die soon.

At night, when he was asleep, she had opened the safe again. It was full of money. She had not counted it all, but without the bonds — they would be dangerous — there was nearly ten thousand dollars in currency. Her hands shook at the memory.

She could have taken it then, and gone away, but three things had restrained her. First, there was a lingering scruple of professional ethics, at deserting a patient in the middle of the night. Then, he might waken suddenly and understand, and she knew that in a drawer of the bedside table was a loaded revolver. He was probably too weak to use it, but once in a while he gathered sudden accesses of strength. And finally, it would be quite obvious where and how the money had gone. Marsden would tell the doctor in the morning, and they would have hold of her in short order.

But she must get it. She must. There were urgent reasons. There was her own realization that time was slipping past her, that professional calls were growing fewer, that there was nothing saved. And there was Terry.

Terry had been her patient once, long ago, before she knew anything about him. He was just a rich man taken ill in a hotel. That was when she was young and full of ideals and rigorous virtues. Probably, if she had never met Terry, the money would have lain in that safe forever for all of her. But after they had fallen in love she had found out — gradually. Terry was a professional bank-robber: that was the bald truth of it. He was also handsome, cultured, fascinating, and she was mad about him. Slowly his in?uence conquered all the ideals and most of the virtues. If she had been scrupulous and honest since, it was from expediency, not from principle. And then Terry had been caught. But he had not been armed — Terry was too wise ever to carry a gun — and he had received a light sentence — ten years. He was a model prisoner; with good behavior, his term would be over now in three more months. They were going to be married when he got out. He must never run such risks again; she must have money for him — plenty of money. They must be able to go away somewhere, change his name, live new lives. It was with Terry, in whispers across a high-ridged table in the visitors’ room, that she had planned this thing.

From Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives by Sarah Weinman. Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © 2013 Sarah Weinman.

For more information, or to pre-order a copy, visit: