What if There was a Third Killer in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood?

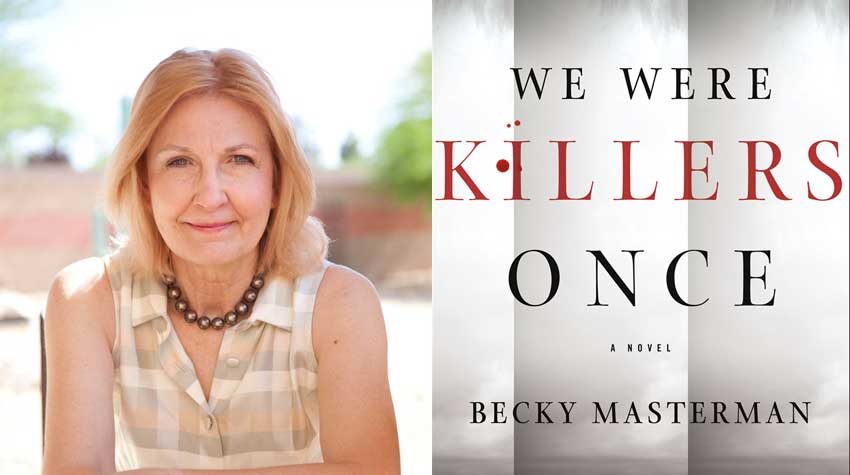

By Becky Masterman

June 3, 2019

Jeremiah Beaufort became my monster while I was thinking of stories for my fourth book in a series with retired FBI agent Brigid Quinn. She adores her late-in-life husband Carlo, an ex-priest. They couldn’t be more different, and she continues to hide her past several years into their marriage.

I was talking to my agent over the phone, and because I hate phones, I was pacing. She said, “I’ve read In Cold Blood a dozen times and I’ve imagined a story where there’s a third man. Another murderer besides Dick Hickock and Perry Smith.”

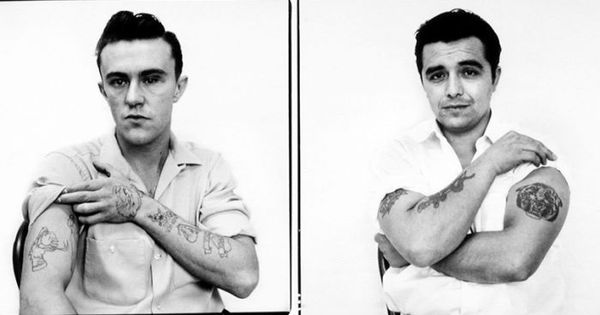

I stopped pacing. “Brilliant,” I said, without confessing I myself had not read In Cold Blood. For the rare individual who shares this aberration, it’s about a family of four in Kansas murdered in 1959 by two petty felons who were subsequently immortalized by Truman Capote. And now I was proposing to riff on a masterpiece, and create a new villain for the story to boot.

“That guy, the third man, has to be alive,” I said, before even picking up the book. “And he’s coming for Brigid’s husband.”

So who is this guy? And what does Carlo have on him?

Would I have to create the creature from nothing, or, like Dr. Frankenstein, find parts of him in the source material of Capote’s book? He would have to be young enough at the time of the crimes to still be dangerous at the time the action of my story takes place. Ideally, he would be as real as Richard Eugene Hickock and Perry Smith, from whose perspective much of the story is told. That’s what makes the book so chilling. So I started to read In Cold Blood, searching for clues.

My villain was waiting to be discovered on page 207. After the mass murder in Kansas, Smith and Hickock were headed east, planning to spend the Christmas holidays in Florida. “Perry noticed them first—hitchhikers: a boy and an old man… The boy—a stocky, sharp-eyed, talkative towhead of about twelve—was exuberantly grateful.” Perry Smith must have gone on at some length about the boy who is never named. Capote offers four pages of recounting how Smith and Hickock picked up the hitchhikers, gathered empty bottles along the road, and dropped them off after splitting the proceeds from the bottles. In light of the rest of the story, it’s a remarkably insignificant episode to be given so much attention.

Why did Perry Smith talk so much about the boy? And what if much of it was a lie? What if he and Hickock picked up the duo before they got to the Clutters instead of afterward, then got rid of the old man, and the young boy stayed with them through their travels? What if the boy was worse than either Smith or Hickock imagined, but Smith grew so fond of him that he changed his confession to take responsibility for all the Clutter murders in exchange for Hickock keeping his mouth shut? Using the pieces provided by Capote, the boy would become my monster.

From there my own story of Jeremiah Beaufort grew. In 1957, when he was twelve, Beaufort killed his little brother with a shotgun near Pascagoula, Mississippi. He said it was an accident, but went to a reformatory for two years. When he came home, his parents wouldn’t let him back into the house. The house burned down with the parents inside; that was an accident, too.

But Jeremiah Beaufort doesn’t think he’s a killer, or rather, he was only a killer once. He tells himself that in order to be a killer you must enjoy the act itself. He first experiences that pleasure when his fate crosses that of Richard Eugene Hickock and Perry Smith. Then he wants to feel the pleasure again.

Of course, he doesn’t see himself as a monster. No one does. Maybe like the rest of us, he regrets some of the things he did in his youth. Maybe he looks back on what he did as a young man with a disgust that haunts him. Maybe he tells himself that if he’s kind to small animals and doesn’t beat his girlfriend, it shows that he’s not a villain at his core. That there was only that one time, okay, two times when he was a killer for the thrill of it. That any other time he has killed, it was out of necessity. Even the occasional nightmares he has about the things he did, these nightmares are an odd comfort because they tell him he must be normal.

Hell, just because you’ve been a mass murderer doesn’t mean you’re a bad man. He tells himself that he’ll never be tempted to kill for pleasure again.

But where has he been all these years, and why has he just resurfaced, a current danger to all who get in the way of making sure his long-ago secret is kept?

For nearly thirty years Beaufort has been in prison, a victim of the Three Strikes and You’re Out law passed during the war on drugs, that committed you to life imprisonment if you were caught three times. Then he got out.

You can only keep up with the culture so much when you’re behind bars that long. You’re likely to know the big events in the news, but if you want to keep your past a secret it’s the little things that give you away. Things like thinking Chablis and Burgundy are still the house wine in a restaurant. Or calling someone a “women’s libber.”

Beaufort imagines himself to be smart, though, with a brain “as sharp as a surgeon’s scalpel.” So he listens carefully, picks up on social cues, and thinks he’s doing a good job of covering his tracks. This despite the question: how stupid do you have to be to get caught three times?

Worse than that, there have been developments in forensic science since the eighties, developments in DNA and latent print analysis. Beaufort is terrified that someday these developments will connect him to a bloody fingerprint or a trace of semen.

And to top it all off, Beaufort gets wind of another confession that Dick Hickock wrote just before his execution.

It’s enough to make even a stone-cold killer sweat. But Beaufort thinks that Carlo has a copy of the confession, and heads to Tucson where he and Brigid live. While he’s confident of finding the confession and silencing the man who has it, he has no idea what he’s actually up against.

Because Brigid was a killer once, too.

Photo © Neal Kreuser