“Things Got Broken”: Anthony Bourdain, Crime Fiction, and the Power of Food

By Lyndsay Faye

June 29, 2018

“It’s been an adventure. We took some casualties over the years. Things got broken. Things got lost…” –Anthony Bourdain

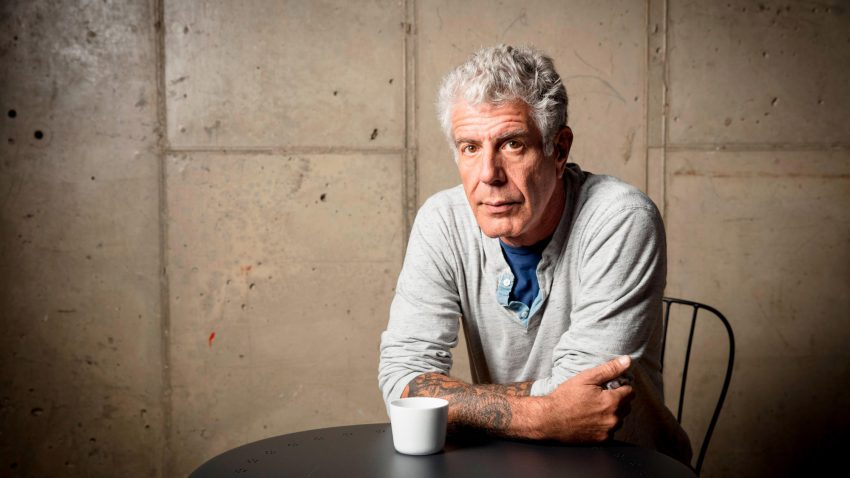

Without an instant’s hesitation, I confess: I write about the late Anthony Bourdain as an avid admirer. Despite his worldwide celebrity chef status, in recent days, I’ve been gratified to note that he’ll be remembered first and foremost as the sort of venturesome romantic about which genre fiction fans most adore reading, not as the overhyped star of a reality cooking show or the owner of a transcontinental chain (he was, thankfully, neither). We mystery enthusiasts favor the sort of amber-lit alleyways that can conceal either a corpse or a secret burger dive, the kind of restaurants that echo with hushed conversations between Mob bosses as well as the hiss of champagne sliding into sparkling crystal flutes. Bourdain traversed these shadowlands—his 6′ 4″ frame slightly stooped, and his skin the deep, scarred brown of a beloved cutting board—and he invited us to tag along. A former chef who worked his way up from dishwasher to television celebrity, Bourdain was voracious not only in his lust for savory noodles and cold beer but for the sort of down-to-earth conversations both aforementioned social lubricants help to enable. He was infamous in his egalitarianism, rabid in his globalism, and loved for his humanitarianism.

He was also a dedicated crime junkie, in more ways than one.

In the wake of Bourdain’s tragic death at the age of 61 in Strasbourg, France, more is being mourned than a father, a partner, a friend, an activist, an icon, and a passionate ambassador for tolerance on a planet that seems obsessed with slamming its doors shut, deadbolting them, and planting landmines along its hallways for good measure. We also grieve over the stories he won’t be telling us and the gore-spattered thrillers he won’t be writing. As Sarah Weinman said in her memorial for Vulture, “… I kept hoping, foolishly perhaps, that Bourdain might return to his first writing love, to the books he wrote and published when his audience was smaller, but still devoted.” The gritty, tongue-in-cheek novels she and so many others enjoyed include A Bone in the Throat, Gone Bamboo, and finally, The Bobby Gold Stories, published between 1995 and 2001. In all three, Bourdain displays a flair for grotesque violence, a gusto for sense memory, and a knack for wry melancholy that would have served future forays into the underworld very well indeed.

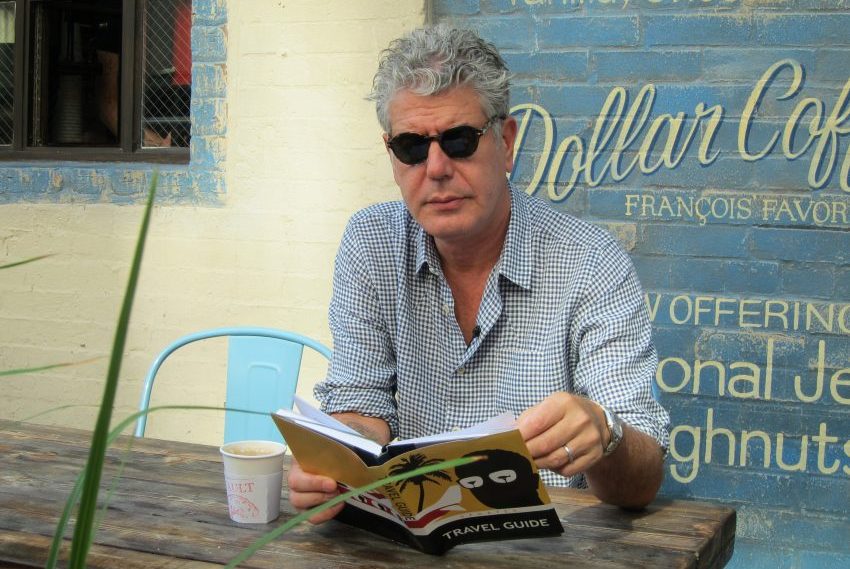

Bourdain ultimately chose to explore the underbelly of the restaurant business in his justly bestselling Kitchen Confidential rather than continue spinning us mobster yarns. But his passion for wordsmithing never waned, and occasionally, on episodes of No Reservations or Parts Unknown, he can be spotted slinking into a rare bookstore like an oversized lynx, obviously salivating. Favorites he listed for Business Insider online in 2013 reveal tastes as eclectic as his palate, ranging from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson to The White Album: Essays by Joan Didion to Ripley’s Game by Patricia Highsmith. In a show of psychic solidarity to which 99% of crime writers residing on Earth will relate, he confessed in a 1997 interview for the New York Times that he felt like writing thrillers was “… a scam I’m getting away with … Doubts gnaw at me when I’m writing. Doing the actual work is tough.” Perhaps as a consequence of such doubts and self-criticism, an absence inside him that he would later “hesitate to call a disease” before a group of opioid abusers on Parts Unknown, his familiarity with crime eventually progressed beyond the theoretical. As he put it in the aforementioned Times interview, “I disappeared. I hung out with really bad people, did really bad things and either didn’t work or bounced around from restaurant to restaurant. I bought into the whole rock ‘n’ roll ethic—drugs, booze, everything—and built my personality around it.”

While it would be ludicrous to suggest that every mystery author has flirted with the dark side in real life—or that all of us even like Anthony Bourdain—I’m under no illusions that the reason I followed his globetrotting song and dance so avidly is because I tick YES boxes for both the former and latter. Addiction, depression, and suicidal tendencies are not strangers to me or to my family. And part of Bourdain’s appeal was the simultaneous brutality and elegance of his honesty. He was candid about his past debauches, even proud of them, as if calling the devil by his name helped to banish him. That frankness—and the willingness to be a good houseguest even to the point of consuming beating cobra heart, fetal duck egg, raw seal eyeball, and most notoriously, unwashed warthog anus—made him the immediate confidante of strangers sharing a common meal rather than a common language. “Behold the worst meal of my life,” Bourdain said ruefully of the dung-crusted warthog orifice. But he went on, “The chief is there in front of his whole tribe offering you his very best. Show respect. I’m lucky to be there. I’m lucky to see that. I’m lucky to have that experience. Chewing some antibiotics is a small price to pay.”

I used a map generator to calculate how many countries I’ve been blessed enough to visit in my 37 years. It came out to 23 (although, I maintain that Ireland, England, and Scotland should be counted as three instead of one). By 2017, Bourdain was nearing his 100th, according to the New Yorker. To say that he had a profound impact on my wanderlust would be an understatement. But still, more than his sincerity regarding mental illness and his peripatetic poetry, I identify with his concept of cooking as an expression of goodwill. Eating together, whether with a godmother, stepdad, sibling, lover, enemy, or total stranger, is a powerful act—and cooking for someone with your own hands still more intimate. As Bourdain told Dave Davies on NPR, offering someone food “changes the whole nature of the relationship. I mean, when somebody’s offering you food, they’re telling you a story. They’re telling you what they like, who they are. Presumably, it’s a proud reflection of their culture, their history, often a very tough history.” When I began learning how to cook, it was motivated by student loans. Later, as I made more money in restaurants, it became about curiosity and a genuine love of good eats passed down through my mom and grandma. And now that I’m, if I do say so myself, pretty adept with the gas flame and the microplaner, I cook to welcome people into my home and to show them affection. Nights that guests are present, we eat grilled whole sea bass, tacos with homemade corn tortillas, roasted pork belly; if I’m writing or researching alone, I’m unwilling to do more than pop the lid on a sardine tin and bust out the Triscuits.

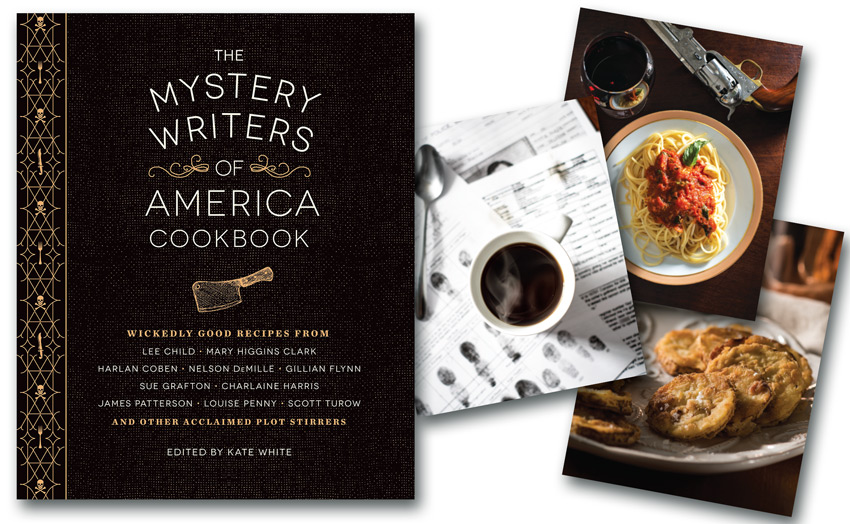

When the MWA produced The Mystery Writers of America Cookbook and asked me to contribute a recipe, I couldn’t imagine inventing one except through the eyes of Captain Valentine Wilde. I first introduced Val—a very loosely interpreted avatar of myself, as most of my protagonists end up being—in The Gods of Gotham, and he continues to play a pivotal role in sequels Seven for a Secret and The Fatal Flame. A brash, wry, gregarious, flamboyantly dressed thug with a bevy of luscious female consorts, a devoted British boyfriend, and a morphine problem, Valentine struggles to produce so much as a harrumph of verbal affection toward his scrapper brother, 19th-century NYPD “copper star” Timothy Wilde. Yet throughout the trilogy, he proves a zealous home cook, lobbing potent insults and immaculate foodstuffs at his younger sibling in displays I can only refer to as autobiographical. Eventually Tim—who is a bit dense regarding his nearest and dearest—catches wise. “You napped a crate of oranges off the back of a wagon once,” he remarks through tears in The Fatal Flame, recalling the orphaned boys’ penniless brushes with starvation. “We were kings for a whole week. Remember?” It’s the closest he comes to telling his only surviving kin “I love you” in the entire trilogy. For the MWA cookbook, I consulted recipes from early American guides to homemaking and carefully recreated a chicken fricassee with touches of Val’s exuberant flair. The mere idea of cooking it by myself, for myself, is physically off-putting. Tony, Val, and I are cut from the same tablecloth.

In an arresting article for Eater.com titled “Fiction Confidential: Is the Real Anthony Bourdain Lurking in His Early Novels?,” critic Maria Bustillos identifies uncanny parallels between the chef-author’s true confessions and his fictional counterparts in ways I find disturbingly familiar as a writer. She takes special note of a passage from Gone Bamboo in which Henry Charles Denard, an assassin trained by the CIA who is all but identical to Bourdain in physical appearance, drives drunk and alone along a perilous mountain road:

A few hundred yards ahead, the road took a steep drop down the other side of the mountain to the sea. The road was ungraded and unbanked; one could easily fly right off the side of that mountain, and Henry considered that option, toyed with the idea as if playing with himself, not serious, just to see how bad things were…

Bourdain later essentially repeated this anecdote, but in a nonfiction setting, for his 2010 memoir collection, Medium Raw. While careful not to leap to any explicit conclusions, Bustillos rightly finds it “distressing, to think that this beloved figure has been picturing such a terrible moment for so long, for reasons we may never know.” And while any author worth their salt, so to speak, will make an effort to conduct proper research before wading into unfamiliar territory, Bourdain’s fiction frequently rings as true as his nonfiction. When describing a heroin-addicted chef begging to be admitted into a methadone clinic in A Bone in the Throat, he writes fluidly:

The person being medicated would add orange drink to the cup from the plastic pitchers on the counter and then stir the mixture with thin wooden stirrers. It was typically a swollen, puffy-fingered hand, covered with purple stripes and scar tissue, that would raise cup to mouth.

Bourdain, by his own admission, was enthralled by glamorously transgressive behavior from his youth. He went through a phase sporting nunchucks discreetly strapped to his thigh, openly listed an impressive array of drugs his fellow cooks and him marinated themselves in when he published Kitchen Confidential, and idolized punk rock bands like The Ramones. In one of my favorite of his essays, “A Life of Crime,” he waxes rhapsodic about his love of reading crime novels, writing crime fiction, and streaming the true crime accounts playing on the CourtTV channel as the soundtrack to life at his apartment:

While I sip my morning coffee in bed, friends are betraying friends on the stand, pathologists coldly recite the particulars of damage to bones and tissue, stone killers affectlessly describe the circumstances leading up to murder, dismemberment, arson…and worse. Lawyers aggressively examine and cross-examine, shrieking with feigned outrage, while outside my windows, car alarms whoop and wail—the occasional urban percussion of shattering safety glass when yet another young entrepreneur makes off with a car stereo. It’s like jazz to me, and I miss it when I’m away. The familiar criminal sounds are almost comforting.

Bourdain loved New York, from glassed-walled towers to Alphabet City drug dens. And he loved the rest of America as well, in a deeply patriotic sense, the sort that eagerly flings the door wide and suggests here, try some of my food, and I’ll try some of yours rather than the variety that peers suspiciously through the peephole. He was a champion of authenticity who was still down to earth enough to admit his drunken-midnight-mistake food was a tub of “The Colonel’s” questionably orange macaroni and cheese. At the time of his death, he was actively hard at work on a massive project at Pier 57, which was meant to become a 155,000 square foot cafeteria featuring dozens of ethnic and regional cooking styles imported from foreign food stalls championed by Bourdain. It was set to open in 2019.

Countless people have expressed shock in the wake of Bourdain’s death, and in many ways, they’ve every right to do so. In an ever-darkening campaign against misogyny, why should we be robbed of an outspoken #MeToo advocate? In an increasingly bleak political landscape, must we suffer the loss of a true ambassador for his country? In times rife with unkindness, can’t we keep the man who famously saved an elderly Olive Garden reviewer from online ridicule and sent an 11-year old leukemia sufferer on a culinary tour of Spain? But to those who read his work with care or who happen to be familiar with disorders of the mind, a bleakness underlines his prose that strikes a chord—one which many of us have experience resisting. To any who are doing so now, I urge: resist a little longer. And then a little longer after that. Seek help. I’ll close with a passage from the essay “Advanced Courses,” which is grim and funny and thoughtful and classically Anthony Bourdain:

They come to [my] readings in their civilian clothes, but I know them from their faces—the gaunt, haunted, thousand-yard stares, the burns on their forearms, the pink and swollen hands, the way they hold themselves in that permanent defensive crouch. The look that says, “Expect the worst and you’ll never be disappointed.” In those faces there’s pain, hope, and a deep appreciation for irony.

Bourdain wasn’t referring to victims of violence or even the battered shells of men haunted by our criminal justice system; he was referring to cooks. And I hope that wherever he is now, as he explores entirely new planes and new vistas, he will never again be disappointed.

Comments are closed.

Thanks for writing this. It’s beautifully done and now I must read his crime books. Thank you

Very nice piece, but just a fyi that would have been easy for you to have researched – the Pier 57 project was nixed last December. Bourdain still planned to some day do “something” along those lines somewhere else in NYC, but there were no plans in the works.

Well done. Sharing now!

Nice post! This is a very nice blog that I will definitively come back to more times this year! Thanks for informative post

This article is really very interesting and effective.Thank you for sharing I think you should also write an article about pet bowl manufacturers