On a cold night, at the outskirts of a peasant village, two Spartan youths wait to perform an ancient rite of passage. A family—father, mother, and their son—approaches, unarmed and defenseless. The young men step into the moonlight and claim their manhood by killing the adults. The boy escapes.

The Spartans have no idea how terrible an enemy they have called forth. Nothing could have prepared them for the boy, Protos, whose name means “destined,” whose cunning and inborn skill with weapons renders his enemies almost defenseless, and whose heart knows no pity. The Spartans have oppressed his people for centuries, and to break their power is to free all those they hold in subjection. As Protos grows to manhood, he begins to understand that his private war against his parents’ murderers is also a struggle for liberation.

1

It was the coldest autumn anyone could remember. Eurytus sat in the shadow of a rock face, tapping the flat of his dagger against his knee as he cursed not the cold but the moonlight. He hadn’t eaten in two days and the moon was as bright as a new gold coin. The night sky was nearly cloudless.

The valley beneath them seemed a stark landscape, full of hard lines and deep shadow. A faint wind blew across it, but the naked branches of its few scattered trees hardly stirred. In daylight it probably would have appeared a different place, but at night, in the tarnished moonlight, it was the land of the dead.

His brother Teleklos was asleep and untroubled by such reflections.

“Go out and wet your blades,” their father had told them. “A warrior kills, without remorse or pity. Become warriors.”

A quarter of a century before, their father had wet his blade in Helot blood. Eurytus thought him very like Teleklos in temperament, endowed with a warrior’s perfect confidence. In his middle forties he was still tall and slim, broad shouldered and powerful. With his black hair and pale blue eyes, which both his sons had inherited, he had the face of a bird of prey.

“To have both of you selected for the Krypteia is an honor for our house. We have too many Helots as it is. When you need food, steal it. Plunder them, even of their lives, and prove your manhood.”

The difficulty was that the Helots also seemed to know about the Krypteia and after dark they mostly kept indoors. It was rare to catch anyone on the roads at night and to venture into their villages might be to disappear forever.

Three days ago they had almost surprised a herdsman, but he saw them in time to save himself, scampering away like a rabbit but leaving behind a reed flute and his dinner bag. They had shared a small loaf of bread and a piece of goat cheese wrapped in leaves.

They had been on the march ever since, farther and farther south, hoping that, a day and a half’s march from Sparta, the Helots might feel themselves safe.

Eurytus knew it might prove necessary to enter a village. They could not return home until they had each made a kill—better to die the worst death than to face the dishonor of failure. But the mere thought of venturing in among the Helots made his skin tingle with fear.

And his fear shamed him. Fear was unworthy of a Spartan and yet it would come, unbidden. To be torn apart by a mob of slaves …

At the ceremony it had seemed so simple. The Elders together had offered sacrifice of a kid at the shrine of Artemis and declared the annual war against the conquered peoples, thus absolving of blood guilt any who killed a slave—who was, in any case, the property of the state—and the ten young men who would go out in pairs to accomplish the rite had been selected from among the best of those who had just finished their military training. Eurytus, described by his instructors as the perfect soldier, brave, disciplined, and cunning, had known he was certain of a place, and Teleklos had been almost as deserving.

“You will enjoy yourselves,” their father had said as Eurytus and Teleklos set out. “It is no different from a hunting party, except that you kill men instead of deer or wild boar—and, trust me, wild boar are more dangerous than the Helots. They are slaves in their souls.”

So they had each been given a dagger and a leather bag full of water and had been sent off south over the hills.

But Eurytus knew this would be no deer hunt. Even a slave will fight for his life. And one man, or even two, cannot prevail against twenty, not armed with a blade no longer than a crow’s wing.

The Krypteia was a test of stealth, no less than of courage. Hence the name: the Hidden. One concealed oneself during the day, for to be discovered was to hazard death, and at night one stole food and killed.

“We will have to go into a village,” Teleklos announced, now apparently awake.

“It is a serious risk.”

“Nevertheless, we have to eat. And when should a Spartan be afraid of risk?”

Teleklos grinned, as if issuing a challenge—and what else could it be? In the moonlight Eurytus could see his face clearly. It was like seeing his own reflection.

They were twins, in appearance as alike as two halves of the same apple yet, like the halves of an apple, not quite identical. The difference was a reflection of their temperaments, which were at odds. Eurytus had long recognized a streak of madness in his brother. Teleklos was not as gifted in intellect, but he was recklessly brave. Aside from skill with weapons, it was the only virtue he thought a Spartan needed. He was born to be a hero, yet would never command troops in battle.

They were near a road, really more of a footpath, a pale streak running north and south between two villages. The brothers had positioned themselves so that they had a clear view of its length, a distance a man might walk in little more than an hour.

“We will wait until the moon is directly overhead,” Eurytus said finally. “If no one has come along by then, at least we can be sure the villagers will be deep asleep.”

“They are asleep already. They sleep like cattle.” Teleklos laughed quietly. “They are cattle.”

When Eurytus didn’t respond, Teleklos apparently felt encouraged.

“It will be easy,” he went on. “We go into a hut, we kill everyone there before they have a chance to cry out. We steal some food, and then it’s home again.”

“Have you ever been inside a Helot village?”

“No.” Teleklos shook his head. “And neither have you.”

“True. But I have wit enough to realize that I have no idea what we might find there. The Helots are poor. Even from the outside we can see that their huts are small. For all we know, they probably sleep like dogs in a kennel—parents, grandparents, little children, uncles, cousins … There might be ten or twelve in one room, covering the floor like rushes. We can’t kill that many without someone living long enough to raise an alarm. We will wait.”

“I’m hungry now.”

“Nevertheless, we will wait.”

This was met with sullen silence. Brave as he was, Teleklos had never learned to defy his brother. Instead, he hunched his shoulders and went back to sleep.

Let him sleep, Eurytus thought.

“I’m hungry now.”

It had been exactly the same when they were eleven years old and their military instructors decided that the boys were becoming sluggish.

“A Spartan should be strong enough to fight on an empty belly,” one of them had announced. “Too much food is turning you into women. Corinthians can be women. Athenians can be women and no one notices the difference. But Spartans have to be men. Learn to do with less.”

After five or six days the boys learned they could not “do with less.” Some tried to run away, to return to their parents, which, of course, was impossible. A few just curled up on the ground and couldn’t be roused.

Teleklos’s solution was more drastic—he wanted to attack the instructors’ mess in the midst of their evening meal.

“Don’t be a fool,” Eurytus had told him. “What can you achieve except a sound thrashing and perhaps even expulsion? Then, if you’re not a Spartan anymore, what are you?”

“I’m hungry.”

“Wait.”

“I’m hungry now!”

“Wait until tonight and we’ll steal some food.”

“How will we do that?”

“I’ll think of something.”

It was summer and the training was entirely out of doors—even Homer was taught under the shade of an olive tree. The boys slept on the bare ground. Cooking was done over pits dug in the earth and filled with coals. The larder was in a tent to keep the flies off.

Of course the instructors pitched their tents all around it, so one had to be quiet.

In the darkest part of the night, Eurytus nudged Teleklos awake.

“Let’s go.”

There was a sliver of moon, so they had just enough light to find their way. The night air was thick with cold and Eurytus was shivering—but more from sheer excitement, he suspected. It was like war except, probably, without the threat of death. He had no idea what the punishment might be for stealing food, but it would be bad.

The tent was secured to the ground with pegs. It was no more than a matter to prying one loose and slithering in beneath the flap.

Once inside, they could smell bread.

“We take two loaves and we leave,” Eurytus said, his voice hardly more than a whisper.

“And some beer and cheese.”

“Teleklos, listen to me—”

But it was already too late. Where only a few pale slivers of light came in through the tent seams around the roof, Teleklos was stumbling among shelves of jars that might have held anything from wine to cooking oil. Almost immediately one of the shelves collapsed with a crash.

And then Teleklos began cursing loudly because a jar had landed edge down on his bare foot.

Eurytus could already hear a murmur of alarm from the instructors’ tents. They had hardly a moment before they would be discovered, and someone would have to take the blame.

But perhaps not both.

Ever since they were six years old, keeping Teleklos out of trouble had seemed to be half the business of Eurytus’s life. Whatever punishment was about to be visited upon them, Teleklos was so rash that he would make it ten times worse for himself. It was necessary to get him out of there.

Eurytus felt around on a table and found a heavy butcher’s knife. He used it to cut a large rent in the back of the tent and practically kicked Teleklos out through it.

“Hide yourself,” he whispered tensely. “Better yet, go back to bed. Get away from here.”

Once Teleklos was gone, Eurytus sat down in the dark, awaiting the inevitable, his heart clenching with fear.

The instructors were not pleased. Eurytus was whipped on the soles of his feet until they ran with blood and then they were wrapped in vinegar-soaked rags. It was a fortnight before he could walk.

He had endured his punishment without crying out.

When he had recovered, he took Teleklos out into the woods and thrashed him. Teleklos did not even attempt to defend himself—he knew he deserved it.

“I was punished for being caught,” Eurytus told him. “You have been punished for being stupid. Next time, listen.”

It was advice Teleklos had heeded through all the years that followed.

“And next time I’ll go steal food on my own.”

And he did, always bringing it back to share with his brother. And he was never caught again.

So, hungry or not, Teleklos would listen and they would not go into a Helot village unless they had to.

Perhaps half an hour later Eurytus jarred him awake.

“Look down there.”

Eurytus was pointing toward the northern village, where a tiny rectangle of light had appeared.

“Someone has opened a door,” he said softly, as if afraid that someone, perhaps a thousand paces distant, might hear him.

“Whoever it is probably only wants to come outside to piss,” his brother answered, sounding annoyed.

“Who would trouble to light a lamp for that?”

The light seemed to flicker, suggesting that perhaps someone—perhaps more than one—was passing in front of or through the doorway. Then, suddenly, the light collapsed.

And all at once Teleklos became as alert as a hunting dog.

“There is movement,” he announced, with a low rumble of laughter. “Two—no three. They are walking toward the road.”

“A family, do you think?”

Eurytus stared into the distance, seeing nothing. But he was prepared to take Teleklos’s word. Teleklos had the eyes of a hawk.

“Two adults, one a head taller than the other. And a third not quite as tall as either.”

“That sounds like a family.”

“If it is, I claim the woman.” Teleklos grinned. He had a taste for that sort of thing.

“As you wish. But then you kill the child as well. I will take the man.”

* * *

Uncle Neleus was dead. Protos could see the grief in his father’s face, the way his teeth drew away from his lips and the flesh around his eyes appeared to thicken. Uncle Neleus had been his father’s brother, his elder by two years. For himself, Protos had been astonished by just the naked fact of death. At fourteen he knew well that people died, just as he knew that the gods lived on Mount Olympus. But his uncle’s death had shocked him, no less than if a swan had waddled in through the doorway and then transformed itself into Father Zeus.

Eventually he supposed he would grieve, like his father, for he had been fond of Uncle Neleus, who could tell wonderful stories. But not quite yet. He still had to recover from the surprise.

His mother and Aunt Nausicaa were weeping. Uncle Neleus had been sick for almost a month—no one seemed to know what from—but perhaps they had not expected him to die. Cousin Mantios, having run the whole way from his village, had entered their house late that afternoon to tell Father he had best come at once if he wished to see his brother alive. Mantios was the same age as Protos, but Protos was almost a span taller.

And now Protos, his father and mother stood outside in the darkness.

“Let us go home,” his father said. “For these few hours he belongs to his wife and children. We shall return in the morning and his sons and I will dig my brother’s grave.”

His father smiled, but his kind, triangular eyes were sad. He put his hand on Protos’s shoulder and looked up into the night sky.

His father was his hero and model. His father knew everything and could do everything, and in every word and action he was quietly, unobtrusively noble. It was from him that Protos had inherited his height, just as his wheat-colored hair was from his mother.

The path out to the main road was narrow so they walked single file, his father first, then Protos, then his mother. A year ago, Protos would have been last. But he was nearing manhood now. When they reached the road he would walk beside his father, who might describe to him the burial rites that would take place the next day. His father was his teacher now. His father was the best man alive.

The moon was huge and directly over their heads. Except for the depth of their shadows, it might have been day.

The moon was a goddess named Selana. She had whelped many children and when she was big like this it meant she was near her travail. Perhaps her pains were upon her and made her wrathful, for the full moon was said to be a dangerous time.

They had just reached the end of the path when his father stopped, putting his hand on Protos’s shoulder. Two men were standing by the edge of the road. Suddenly, like wicked spirits, they were simply there.

In an instant the moon, with supernal mercilessness, revealed everything. The two men were strangers and, stranger still, precisely alike. And in their hands they held knives.

“Protos! Antheia!” Father shouted. “Run! Save yourselves!”

Mother screamed—it was like no sound he had ever heard. She turned and fled. Protos could not understand what was happening.

“Run, Protos! Now!”

Death suddenly felt so close. Protos ran like a startled deer.

Sixty paces from the road the ground became a wilderness of rock, trees, and brush. No one ever went there except small boys who wished to play. There was no other reason to go there. Beyond were only the hills and beyond them the barren mountains.

Just at the edge, before Protos plunged into that trackless waste, he heard something that made him stop. It was like a sob, cut brutally off. He turned and looked back. What he saw would live in his memory until he was dust.

His father was on the ground, curled up like a newborn, his hand clutching at his guts, his legs kicking strengthlessly. Even at that distance, Protos could see the bright blood welling out between his fingers.

And his mother was on her knees. Protos did not have to hear her words to know she was begging for her life. One of the two strangers had her by the hair, his knife raised.

“Teleklos, stop toying with the woman,” his companion shouted. “Get the boy before we have the whole village down on us.”

With a stroke the man called Teleklos cut Mother’s throat. Protos saw a spray of blood and then she fell over sideways and lay twitching on the earth as she died.

“The boy, Teleklos!”

Protos did not wait. He ran, jumping over rocks and fallen trees, hardly conscious of the sharp little stones that tore at his feet. He headed into the deepest undergrowth, hoping to find a hiding place.

But even as he ran he knew flight was hopeless. There were two of them and soon they would both be upon him. And they were men while he was only a boy. They would run him down quickly enough.

He might hope to escape only one. One he might be able to evade. So he would have to do something about the one who was nearer. Teleklos—somehow knowing his name rendered him less terrible.

So it was Teleklos he had to stop. The means were everywhere around him.

“My son Protos can kill a crow at fifty paces,” Father had once bragged to a neighbor. “Give him a pebble no larger than a grape, and he’ll knock its eye out.”

“Not a very practical skill for a farmer,” the neighbor had responded, and then laughed.

“Here, boy, show me what you can do,” he went on, picking up a small stone and tossing it to Protos. “Hit that fence post over there and I’ll give you a swallow of my beer.”

Protos had been eight years old, and it was the first time he had ever tasted beer.

“No one can choose the gifts he is born with,” his father had told him once. But this one might now be the means of saving his life.

Even as he ran Protos searched the ground and at last he found it—a stone, almost perfectly round, about half the size of his fist. He ducked low and scooped it up and kept on running.

His pursuer was no more than forty paces behind and closing the distance. Protos struck off to the left, ran about fifteen paces, and hid himself within the shadow of a tree.

He had only to wait. He could feel the pulse beating in his neck. It was as if his heart had somehow become trapped in his throat.

Just there the ground was fairly open. Teleklos stopped and looked about him, no doubt wondering where his quarry had disappeared to. This opportunity would last no longer than an instant.

Protos made his throw. As the stone glided away under the first two fingers of his right hand, he had no doubts.

Perhaps Teleklos saw something, or heard something, because in the last instant he turned his head. The stone caught him on the outer end of his left eyebrow. He pitched over as if struck dead.

But he was not dead. Protos made his approach slowly and by the time he found the man’s knife lying in the grass—still stained with Mother’s blood—Teleklos had begun to groan.

Protos weighed the knife in his hand. He tested the blade and it was very sharp. Suddenly he knew he was going to kill this man.

He wanted him to be awake, to know what was happening to him. It would have been the easy thing to slit his throat while he lay unconscious, but it wasn’t enough. It would not appease the hatred he felt.

He sat down on the ground beside Teleklos’s head, gathering up the Spartan’s long hair in his hand. By then he had come to understand that these men were Spartans—who else would ambush innocent people to kill them for sport?

He let the knife blade rest on the bridge of the Spartan’s nose, allowing it to split the skin until blood welled out and flooded the man’s eye sockets.

Teleklos regained consciousness with a start.

“Don’t struggle,” Protos almost whispered. “Lie still. If you move I’ll dig the eyes out of your head.”

With visible effort, Teleklos became still. He was panting for breath.

Good, Protos thought. Let him be afraid, as my mother was afraid.

“I can’t see.” Teleklos made as if to touch his face, but a touch of the knife stopped him. “Who are you?”

“I am your death.”

“Are you the boy?”

“Yes. You killed my mother, and for that you will die.”

He pressed the point of the knife against the Spartan’s throat.

“You can’t kill me,” Teleklos said, in a voice that was no more than a strangled whisper. “You’re only a slave.”

In answer, Protos drove the blade into the Spartan’s neck until he hit bone. Then he gave the knife a sharp twist. Blood spattered his face.

For a moment Teleklos jerked about like a fish on a riverbank. And then he was still.

“Teleklos!”

Having killed once, Protos suddenly found he had no courage left. All he wanted was to flee.

The moon, merciful at last, stepped behind a cloud and the world went dark. Protos did not run but crept along, working back toward the road. His pursuer would probably expect him to escape danger by fleeing from it, so he would do just the opposite.

In the next instant the air was split with a scream of anguish. Brother had found brother. Protos was perhaps a hundred paces distant, but he could hear the sobbing. For some reason he could not have explained, the sound filled him with remorse.

By then he had gained the road, where he found his parents’ corpses lying in the dirt. Their eyes were open and their blood seemed black in the faltering moonlight.

And remorse died.

He headed east, into the hills.

But he quickly sensed he was not alone. Sometimes, if the wind died away, he would stop and hear the faint sound of sandals scraping against the stony ground. The brother had not been fooled by his doubling back. Somehow, even in the darkness, he was tracking him.

Once, lying on his belly behind a thistle bush, Protos saw him at a distance, watched him hunting over the ground.

He was clever, this one—subtle, where Teleklos had been bumbling and obvious. If he and not his brother had first set out after him, Protos suspected he would have been dead these two hours.

What was he looking for? Footprints?

Protos decided to stay off the paths and try to use the rock face. It would be harder, but he might live to dawn.

Finally, when his strength had all but left him, he found a cave, small enough that he had to crawl inside on his hands and knees. He reached out and pulled some brush over the mouth, hoping that would be enough to keep it hidden.

And he still had Teleklos’s knife. If the other one came in after him, Protos would see to it that he never crawled out again.

It was only in the cave, when he was still and his heart was no longer racing with fear, that he realized how cold the night was. He wondered if he might freeze to death before morning. It gave him a certain satisfaction to reflect that then surely the Spartan would never find him.

“BOY!”

It could have been coming from anywhere—it sounded almost as if he was standing directly in front of the cave.

“You cut my brother’s throat, and I promise I will not rest until I see you crucified over his grave. Do you hear me, boy? I know you are here somewhere. I am Eurytus, son of Dienekes, and I have taken a vow over my brother’s corpse that I will see you die. You will die hard, and you will pray to the gods for death long before it comes. I will find you, boy!”

Protos waited, hardly daring to breathe. Fear sharpens the senses, and a ferret could not have climbed out of his burrow without him hearing it. But there was nothing. Eurytus, son of Dienekes, had been announcing that he had given up. He would be back, but not tonight.

Protos never closed his eyes. Fear and grief kept him awake—and the cold. Yet somehow that night, in the chill, black solitude of a mountain cave, the child died and the man was born.

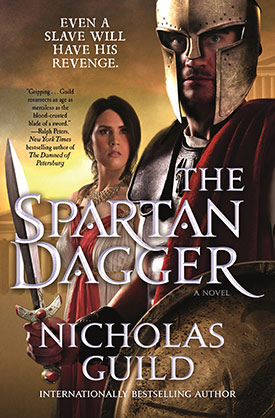

Copyright © 2016 Nicholas Guild.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

NICHOLAS GUILD was born in Belmont, California, and attended Occidental College and the University of California at Berkeley. He taught at Clemson and Ohio State before turning full time to writing fiction. He has published a dozen novels in both the thriller and historical genres, several of which were international bestsellers, including The Assyrian, Blood Star, and Angel. Guild now lives in Frederick, Maryland.