In 1955, the most notorious of Patricia Highsmith’s creations, Tom Ripley, entered her repertoire. Patricia Highsmith’s (1921–1995) debut novel in 1950 was Strangers on a Train, a critical smash. When Alfred Hitchcock directed the film version a year later, she was catapulted into the upper echelons of undeniable masters of the psychological thriller. Slow, simmering plots featuring society’s fringe-dwelling element provided a ripe environment for suspense, and film critic Roger Ebert summed up Tom Ripley’s cunning character best: “charming, literate, and a monster.” Four sequels followed between 1970 and 1991.

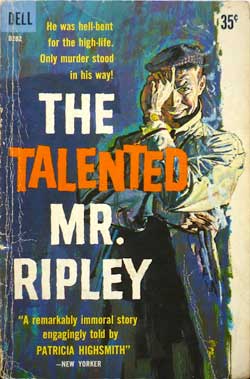

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

Wealthy shipping magnate, Herbert Greenleaf, pays Tom Ripley to go to Mongibello, Italy, and encourage his son, Dickie, to come home. Mr. Greenleaf believes his son and Tom were better friends than they actually were at college, and, unbeknownst to Mr. Greenleaf, the smiling, likable, eager-to-please Tom is the evilest of self-serving sociopaths. Straightaway, Tom endears himself to Dickie, and they form an alliance to continue to milk the old man for money and extend their overseas paid vacations. Dickie has fallen for a woman named Marge Sherwood, who instantly takes a disliking to Tom and undermines him by telling Dickie she believes Tom is gay. When Dickie forgoes spending an afternoon with him, a bitter Tom goes to Dickie’s room, dressing up in his clothes.

“Marge, you must understand that I don’t love you,” Tom said into the mirror in Dickie’s voice, with Dickie’s higher pitch on the emphasized words, with the little growl in his throat at the end of the phrase that could be pleasant or unpleasant, intimate or cool, according to Dickie’s mood. “Marge, stop it!” Tom turned suddenly and made a grab in the air as if he were seizing Marge’s throat.

Dickie tires of Tom and takes measures to cut ties, which is unacceptable to the young man who longs to live Dickie’s life … literally. And to be Dickie Greenleaf, he decides he must kill what he most admires.

Note: The Talented Mr. Ripley was inspired by Henry James’s dark comedy The Ambassadors (1903) that also found an American venturing to Europe to fetch a wayward son.

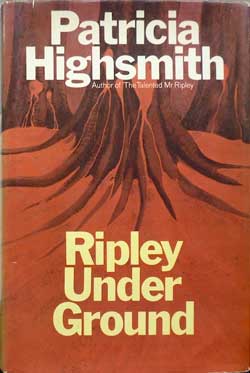

Ripley Under Ground (1970)

Ripley Under Ground (1970)

Then came the stretch of jammed-together Victorian houses that had been converted into small hotels with grandiose names in neon lights between Doric doorway pillars: MANCHESTER ARMS, KING ALFRED, CHESIRE HOUSE. Tom knew that behind the genteel respectability of those narrow lobbies some of the best murderers of the present day took refuge for a night or so, looking equally respectable themselves.

It’s six years since the murderous occurrences that transpired in The Talented Mr. Ripley, and Tom is living, quite leisurely, with his pharmaceutical-heiress wife, Héloïse, in a French villa. Ripley’s lifestyle is supported by Dickie Greenleaf’s fortune and Derwatt Ltd., an art forgery scheme that begins to unravel when an art collector suspects someone is duplicating the paintings of a famous reclusive artist. Ripley invites the suspicious collector to his villa where he attempts to persuade the man to drop the investigation. When the collector refuses, Ripley takes matters into his own hands by giving the man a tour of the wine cellar where … well, you can imagine what follows.

Ripley Under Ground isn’t on the same creative level as The Talented Mr. Ripley—Ms. Highsmith concocts circumstances that will surprise and stretch the believability factor. Still, the ongoing adventures of the gentleman killer remain quite entertaining. Frank Rich writing in New York Times Magazine explained his enduring attraction:

The Brilliance of Highsmith’s conception of Tom Ripley was her ability to keep the heroic and demonic American dreamer in balance in the same protagonist—thus keeping us on his side well after his behavior becomes far more sociopathic than that of a con man like Gatsby.

Ripley’s Game (1974)

Ripley’s Game (1974)

Ripley's Game is by far the weakest in The Ripliad, because Tom Ripley is absent for a good portion of the plot and instead the focus is on the leukemia-stricken Jonathan Trevanny. Ripley and a cohort trick Trevanny into committing murder for money so that Trevany can leave his family some financial assistance after he dies. Ripley begins to feel guilty for getting Trevanny into that situation, shows up on a train, and helps him off a mafia boss and a bodyguard.

Tom saw the nylon disappear in the flesh of his neck. Tom gave it another whirl behind the man’s head and pulled still tighter. With his left hand Tom flicked the lever that locked the door. Marcangelo’s gurgle stopped, his tongue began to protrude from the awful wet mouth, his eyes closed in misery, then opened in horror, and began to have the blank, what’s-happening-to-me stare of the dying.

That particular scene is riveting, but Trevanny isn’t a compelling enough character to sustain the book’s overall satisfaction. When Ripley graces the pages, its transfixing how this murderer lives, operates, and what he thinks in the most minute of observations.

Note: This book contains the highest number of murders that Tom Ripley commits. Two film adaptions were based on this novel beginning with The American Friend (1977) starring Dennis Hopper, and later, John Malkovich masterfully assumed the role in 2002’s Ripley’s Game.

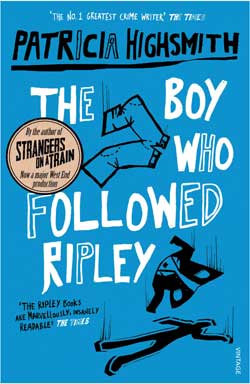

The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980)

The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980)

Frank Pierson, son of a recently deceased American entrepreneur, is a troubled sixteen-year-old, who runs away to France and searches out Tom Ripley. Ripley takes a paternal fondness to the teen and gives him a job gardening, later discovering the youth has killed the senior Pierson. Ripley begins mentoring Frank with the hopes that he will be able to find sustainability in society, as he did, but events transpire against his better intentions when Frank is kidnapped and held for ransom in West Berlin, forcing Ripley once again to kill in order to right his world.

The passages devoted to the sights and sounds of the German city are some of the finest Highsmith composed, though some scenes, like Ripley in drag, come across as a bit forced and formulaic. This fourth installment is artistically on par—hit and miss—with Ripley’s Game, though it has a slight edge, because of the more empathetic Ripley that emerges, the one who sees in the young Frank Pierson his own troubled beginnings.

Trivia: According to Joan Schenkar’s essential The Talented Miss Highsmith (2011), the author originally had Ripley killing Herbert Greenleaf in the first book by pushing him over a cliff with Dickie Greenleaf’s consent. This plot device was resurrected for The Boy Who Followed Ripley, with Frank pushing his wheelchair-bound father off a cliff in Maine.

Ripley Under Water (1991)

Ripley Under Water (1991)

Tom Ripley has the good life he’d so desperately coveted: a wealthy home in the French countryside, a beautiful doting wife, and the authorities no longer interested in the peculiarities of so many homicidal happenstances in his presence. He spends his day painting, playing the harpsichord, and planning expensive vacations. Into this serene existence enter David and Janice Pritchard, who seem to possess some knowledge of Ripley’s crimes. The American couple begin tormenting him by photographing his house and making, what amounts at first, to be prank calls. Ripley apparently knows amateurs when he sees them:

Games, games! Secret games and open games. Open-looking games that were really sly and secret. But of course beginning-and-end secret games went on behind closed doors, as a rule. And the people concerned merely players, playing out something not in their control.

But soon, the Pritchards press him harder, dropping a gruesome delivery at his front door: the corpse of Thomas Murchison. Ripley had slain Murchison in Ripley Under Ground, and the Pritchards disinterred the body by methodically draining various local waterways. Ripley’s come too far as a somebody to have the conniving, unrefined Pritchards just come along and take it away. His ingenious method of clearing away these last obstacles is a fitting ending to an unparalleled series that has inspired so many unbalanced killers since, the most notable being Dr. Hannibal Lecter and Dexter Morgan. But it was Patricia Highsmith’s talented Mr. Ripley that had us rooting for a likable gentleman killer first.

Edward A. Grainger aka David Cranmer is the editor/publisher of the BEAT to a PULP webzine and books and the recent Western novella, Hell Town Shootout.

Read all of Edward A. Grainger's posts for Criminal Element.

Didn’t realize there were so many Ripleys.

The film version of “The Talented Mr. Ripley” starring Matt Damon, Jude Law and Gwyneth Paltrow is an excellent movie. The performances are first rate, especially Matt Damon’s creepy portrayal of Tom Ripley, and the plot subtle and unnerving. The late, great Phillip Seymour Hoffman, in a brief performance, contributes another level to the film.

Highly recommended for those who like moody noir films.

[b]Oscar[/b], the second one is a favorite of mine. Well worth your time.

[b]Drew[/b], Matt Damon is the image of Ripley I see when I read the books. Top adaptation and agree on Hoffman. Superb performance.

David, I have not read any of Highsmith’s novels which is a great disservice to the author and her work.

Prashant, After The Talented Mr. Ripley I’d recommend The Cry of the Owl and Strangers on a Train.

David,

Thank you for the additional info on the “Ripliad” –

I just recently learned there was more to the story of Tom Ripley.

I’m finishing [u]Ripley Under Ground[/u] this evening.

Having now read them all, Ripley’s Game the last, I don’t agree it’s the weakest. (The fact it got two film adaptations obviously argues against that).

These books, much like the much longer and equally brilliant series about the armed robber Parker, written by Richard Stark (aka Donald Westlake) are about comparative psychology. Ripley himself isn’t really that interesting without someone to compare him to. It’s never just about him, and Highsmith can’t write about him without contrasting his reactions to those of others in the same story. To me, this is the most poignant of the books (I wouldn’t care to talk about something as nebulous as ‘best’–best in what way?) Because in a certain sense, Parker comes to like and respect this man whose life he ruins, and his question at the end–haunting. Why did Trevanny do that? Is really the question Highsmith wants us all to ask. I didn’t find Trevanny the least bit boring, and I am saddened by the notion that we find basic decency so mundane. Highsmith put a lot of work into the character, but of course he’s not going to be as sexy as a master con artist and murderer. The fact remains, without contrast, a work of art has no point to it. Trevanny is there for contrast.

I meant Ripley, not Parker. But to me, they are oddly linked characters, and I’ve long thought Westlake and Highsmith were influenced by each other over the decades of writing those two series.