Things aren’t going well for Grayson Hernandez. He just graduated from a fourth-tier law school, he’s drowning in student debt, and the only job he can find is as a messenger. The position stings the most because it’s at the Supreme Court, where Gray is forced to watch the best and the brightest?the elite group of lawyers who serve as the justices’ law clerks—from the outside.

When Gray intervenes in a violent mugging, he lands in the good graces of the victim: the Chief Justice of the United States. Gray soon finds himself the newest—and unlikeliest—law clerk at the Supreme Court. It’s another world: highbrow debates over justice and the law in the inner sanctum of the nation’s highest court; upscale dinners with his new friends; attention from Lauren Hart, the brilliant and beautiful co-clerk he can’t stop thinking about.

But just as Gray begins to adapt to his new life, the FBI approaches him with unsettling news. The Feds think there’s a killer connected to the Supreme Court. And they want Gray to be their eyes and ears inside One First Street. Little does Gray know that the FBI will soon set its sights on him.

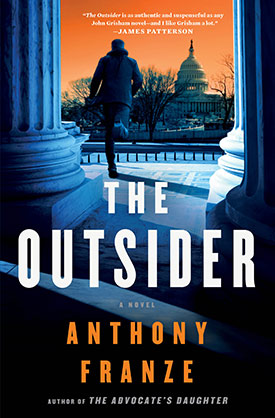

Racing against the clock in a world cloaked in secrecy, Gray must uncover the truth before the murderer strikes again in this thrilling high-stakes story of power and revenge by Washington, D.C. lawyer-turned-author Anthony Franze.

CHAPTER 1

Grayson Hernandez walked up to the lectern in the well of the U.S. Supreme Court. He wasn’t intimidated by the marble columns that encased the room or the elevated mahogany bench where The Nine had been known to skewer even the most experienced advocates. He calmly pulled the lever on the side of the lectern to adjust its height, a move he’d learned watching the assistant solicitor generals showing off. He stood up straight and didn’t look down at any notes; the best lawyers didn’t use notes. And he began his oral argument.

“Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the court—”

He was immediately interrupted, not uncommon since the justices on average asked more than one hundred questions in the hour of oral argument allotted to each case. But the voice, which rang though the chamber, wasn’t from a justice of the highest court in the land.

“I’ve told you before, Gray, you can’t be in here.”

A flashlight beam cut across the empty courtroom. Gray held up a hand to shield his eyes. He smiled at the Supreme Court Police officer making his nightly rounds.

“Someday, counselor,” the officer said. “But for now you might wanna focus on getting the nightlies delivered.” The officer swung the ray of light to Gray’s messenger cart filled with the evening’s mail.

Gray waved at the officer and returned to his cart. The wheel squeaked as he rolled it out of the courtroom and into the marble hallway.

In Chief Justice Douglas’s chambers, two law clerks were sitting in the reception area, fifteen feet apart, tossing a football between them. They seemed punchy, wired after a long day at the office, talking about one of the court’s cases.

“A high school has no right to punish a kid for things he says off school grounds. The court needs to finally say so,” one of the clerks said. He was a stocky blond guy. Gray thought his name was Mike. Mike spiraled the ball to the other clerk, who looked kind of like a young JFK.

“You’re high if you think the chief is gonna side with the student,” JFK said, catching the ball with a loud snap. “You upload a violent rap song on YouTube saying your math teacher is sexually harassing students, you’re gonna get suspended.”

“Even if it’s true?” Mike said.

The Supreme Court had thirty-six law clerks, four per justice. It was an internship like no other, promising young lawyers not only a ticket to any legal job in the country, but also the chance to leave their fingerprints on the most important legal questions of the day. The current clerks were all in their late twenties, the same age as Gray, but that’s where the similarities ended. Like the two throwing the ball, almost all were white, from affluent backgrounds. Gray didn’t think there were any Mexican Americans in the clerk pool, and certainly none who grew up in gritty Hamilton Heights, D.C. They’d all gone to Harvard or Yale or institutions that, unlike Gray’s law school, had ivy instead of graffiti on their walls. And they certainly weren’t delivering mail.

Gray nodded hello as he lifted the stacks of certiorari petitions out of his cart and dropped them in the metal in-boxes for the chief’s clerks.

Mike looked at Gray. “No, not more petitions, I’m begging you.”

Gray smiled, but didn’t engage. His boss in the marshal’s office had a rule when it came to the justices and their law clerks: Speak only when necessary.

The ball whizzed across the reception area again. “Is it printed yet?” JFK asked. “I wanna get out of here.” He looked over to the printer, which was humming and spitting out paper. Gray worked two night shifts a week, and there usually were no less than a dozen clerks still in the office. Theirs was a one-year gig, but they worked as if the justices wanted to squeeze five years out of them.

“It won’t take long,” Mike said. “It’s a short memo, and I just want someone who’s a disagreeable ass to point out any soft spots before I turn it in to the chief.”

“You’re wasting your time. He’s never gonna side with the student, he—”

“This case is no different than Tinker v. Des Moines,” Mike countered. “The court said disruptive speech at school could be punished, but not speech made off school grounds. Off-campus speech, including posting a song on YouTube, should be covered by the First Amendment just like everything else. It’s none of the school’s business.”

JFK gave a dismissive grunt. “A rap expert from Greenwich, Connecticut, I love it.”

Mike threw the ball hard at his co-clerk.

“Hey,” JFK said, shaking off the sting after reeling in the throw. “I’m just saying, the Tinker case was decided in the late sixties. You can’t apply it in the digital world. You’re in an ivory tower if you think the chief will blindly follow Tinker.”

Gray pretended not to listen, but he lingered, enjoying the intellectual banter.

The ball flew by again. “Ivory tower?” Mike said. “Fine, let’s ask an everyman.” He pointed the football at Gray. “Hey, Greg, can we ask you something?”

Mike had once asked Gray his name, a regular man of the people.

“It’s Gray.”

“Sorry. Gray. We have a question: Do you think if a high school student is off campus and posts something offensive on social media a school can punish him for it?”

JFK chimed in: “It’s not just posting something offensive. It’s a profanity-laden rap that accuses a teacher of sexually harassing students and threatens to ‘put a cap’ in the guy.”

Gray pondered the question as he retrieved mail from the out-boxes. “I agree with what Murderous Malcolm said about the case.”

The clerks shot each other a look. That morning the New York Times ran a story about the case, in which a famous rapper was interviewed and defended the student’s right to free speech. Every morning the Supreme Court’s library sent around an e-mail aggregating news stories relating to the court. Gray was probably the only person at One First Street who read them all.

Gray continued. “I think the First Amendment allows a kid who saw a wrong happening to write a poem about it over a beat.” Gray wheeled the cart toward the door. “And if the chief justice disagrees, you might mention all the violence in those operas he loves so much.”

“That’s what I’m talking about,” Mike said, spiking the ball, then doing a ridiculous touchdown dance. He strutted over to Gray and gave him a high five.

For a moment, it felt like Gray was a clerk himself, an equal weighing in on the most significant school-speech case in decades.

“Hey, Gray,” JFK said.

Gray turned, ready to continue his defense of the First Amendment.

“I’ve got some books that need to be delivered to the library.”

* * *

When Gray arrived at the gym two hours later, his dad already had his hands wrapped and was hitting the heavy bag. There was a large sweat stain on his shirt. “You’re late,” he called out.

“I told you, I have the night shift on Sundays,” Gray said.

His dad didn’t respond, just pounded the bag.

He wasn’t going to get any sympathy from Manny Hernandez about the night shift. This was his father’s one night off from the pizza shop. Since his dad’s cancer went into remission, they’d been meeting every Sunday night at the old boxing club in Adams Morgan. Gray would have preferred that they spent these times together somewhere other than a smelly gym, but it made his father happy to see him back in the gloves. It was these moments that Gray was reminded that he probably wasn’t the man his father had dreamed he’d become. With his books and big dreams, Gray was his mother’s boy.

Gray punched the bag, the hits vibrating through him, his thoughts venturing to his encounter with the law clerks. He threw his weight into his right.

Let’s ask an everyman.

Then his left.

I’ve got some books that need to be delivered to the library.

Gray continued to pummel the bag, his heart pounding, sweat dripping from his brow.

“Somethin’ wrong?” His father came and stood behind the bag, holding it in place as Gray kept going at it. “Talk to me.”

“It’s nothing,” Gray finally said, catching his breath, wiping his forehead with his arm. “Just work stuff.”

“I thought it was going well? You’ve loved that building since you were a little kid. And now you’re working there, helping the justices.”

“I don’t think delivering the mail is exactly helping the justices, Dad.”

“It’s a foot in the door. Once they get to know you, see how smart you are…”

Things didn’t work that way, but Gray wasn’t in the mood to argue.

“It’ll happen, son,” his father added. “You just gotta pay your dues, Grayson.”

“I know, Dad, I know.”

Copyright © 2017 Anthony Franze.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Anthony Franze has garnered national praise for his work as a lawyer in the Appellate and Supreme Court practice of a major Washington D.C. law firm. The New York Times, Washington Post, and other prominent news outlets have quoted or cited Franze concerning the Supreme Court, and he has been a commentator on high-court issues for The New Republic, Bloomberg, and National Law Journal. He lives in the Washington D.C. with his family.