The canary, like the cat, has many lives. Especially the black-feathered variety (genus Serinus Something-or-other.) The Black Canary, aka Dinah Drake, first spread her wings more than sixty-five years ago in the August 1947 issue of Flash Comics. Since then, she’s gone on to many identities, costumes, teams, and series.

The canary, like the cat, has many lives. Especially the black-feathered variety (genus Serinus Something-or-other.) The Black Canary, aka Dinah Drake, first spread her wings more than sixty-five years ago in the August 1947 issue of Flash Comics. Since then, she’s gone on to many identities, costumes, teams, and series.

The Canary of the 1940s arrived as a non-powered costumed vigilante a la Batman with a way-cool outfit. She garbed herself in bluish-black fishnet tights, pirate boots, choker, and a blue bolero or Zouave jacket (let the fashionistas determine which). As gratuitously sexy as this getup might sound, it was actually quite sensible and sleek for the modern woman pursing a postwar crime-fighting career. Then there was her hair—long golden tresses that made her look like starlet Veronica Lake. Truth be told, those luxurious locks were, alas, just a wig. When going into action, raven-haired Dinah Drake—like Supergirl, we might note—would slap on a blond toupee. Supergirl probably has some sort of Kryptonian scalp mojo that kept her hairpiece clamped down during battle. Not sure what Black Canary’s trick was.

Dinah actually was a bit of a canary-come-lately on the costumed do-gooder scene. Superman had kicked things off nine years before, igniting an explosion of colorful heroes spanning many comic books and many publishers. Our bird lady showed up just in time to catch the last hurrah of that first wave of gaudy crimebusters. Her initial solo adventures ran only eighteen months, and the fact that she survived a couple years beyond that was only due to her membership in the Justice Society of America. That team barely made it into the 1950s, before it, too, was gonesville. Except for a handful of A-listers and a few backups, most of Superman’s progeny were MIA by the Eisenhower Era—including the Black Canary. Of course, there was the grand resurgence known as the Silver Age of Comics, but that’s another story.

Having recently read a collection of the Canary’s late-1940s tales, I’ve gained a new appreciation of the character. Most of these early stories owe more to noir mysteries than to cape-and-cowl punchfests. Debuting in Flash #86, the Black Canary was initially a supporting character to Johnny Thunder, a non-costumed hero with a crew-cut, bowtie, and naked anthropomorphic thunderbolt. (Yes, you heard me.) After a half-dozen adventures with Johnny, she swiped his slot in Flash Comics, and, from there on out, her stories relied no more on supernatural assistance, but on rough-and-tumble detective work.

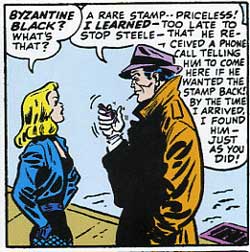

Dinah Drake soon becomes the owner of a floral shop in which “her pet peeve and pet customer, Larry Lance, Private Eye, calls for his daily flower.” This premise becomes the hook for the series, with Larry eventually running his business out of the store. A smug but likable P.I. with dubious deductive skills, Larry had the classic gumshoe look—fedora, pinstripe suit, cigarette dangling from his lips. Basically, he was Bogart Lite. The stories often started off with some contentious repartee between the two characters, usually with Larry coming out on the losing end. The dialogue is snappy, if a bit groan-worthy, as in this exchange from “Corsage of Death”:

Dinah Drake soon becomes the owner of a floral shop in which “her pet peeve and pet customer, Larry Lance, Private Eye, calls for his daily flower.” This premise becomes the hook for the series, with Larry eventually running his business out of the store. A smug but likable P.I. with dubious deductive skills, Larry had the classic gumshoe look—fedora, pinstripe suit, cigarette dangling from his lips. Basically, he was Bogart Lite. The stories often started off with some contentious repartee between the two characters, usually with Larry coming out on the losing end. The dialogue is snappy, if a bit groan-worthy, as in this exchange from “Corsage of Death”:

Dinah: If it’s all right with you Mister Larry Lance, I’d like to close my flower shop for the night!

Larry: Don’t rush me, Dinah! Someone might call to ask me to take over a big case!

Dinah: Case of what—poison ivy?

Prolific scribe Robert Kanigher wrote all these early stories, and Carmine Infantino provided the art. (This team would later create the new version of the Flash, thus revitalizing the superhero genre.)

The Canary cases are seven pages long at most and are unabashedly formulaic. Reading one after another, I first saw this as a liability, but soon began viewing the tales in a different light. I began to see them as multi-paneled haiku with pulpy, poetic titles such as “The Riddle of the Roses,” “The Huntress of the Highway,” and “An Orchid for the Deceased.” Like the terse Japanese poetry form, the blond bombshell’s stories have an unwavering structure. This usually involves: banter among the bouquets, tackling a crime, getting slugged and tied up, and eventual escape and triumph.

The slugging and trussing up part seemed to be particularly essential to these narratives. No matter how vigilant the Canary and her pet P.I. were in tackling their adversaries, one usually managed to sneak up from behind and gun-butt the duo into unconsciousness. From initially moaning not again at each of these trouncings, my attitude eventually became more like, Aha! there it is—the pre-victory sneak-up bashing. Canary’s down but not out, you rats! And, of course, she would somehow find a way to break her bonds and break the case.

Sure, Larry Lance helped out, but it’s significant to note that the Black Canary was generally the one who got things done. Like her fellow heroine (and Justice Society sister) Wonder Woman, the Canary represented female strength, smarts, and capability. But whereas WW was created specifically to offer girls a positive role model, Black Canary’s existence may have been more of an attempt to cash in on the popularity of noir detective fare. Still, Diana came off as tough and tenacious as any star-spangled amazon.

Following a twelve year absence, the Canary returned to the land of comics in 1963 and, in the ensuing half-century, has never left it. In addition to illustrated tales, she’s branched out into animated series, live action television, and video games, acquiring along the way various identities, powers, lovers, and teammates. But, for me, those initial stories from the 1940s hold a particular appeal.

For anyone seeking these early adventures, DC’s hardcover The Black Canary Archives reprints in full color her complete Golden Age solo run, plus a few later offerings. Whether seen as poems or potboilers, these tales, like their protagonist, have spark and spunk.

Michael Nethercott is a playwright and writer of traditional mysteries whose O’Nelligan and Plunkett tales appear periodically in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His first novel featuring this 1950s detective duo, The Séance Society, will be released in October 2013 by St. Martin’s Press.