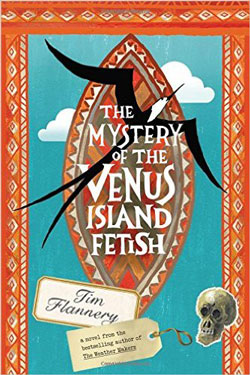

The Mystery of the Venus Island Fetish by Tim Flannery is set in 1932 and follows young anthropologist Archie Meek and the Great Venus Island Fetish—a ceremonial mask surrounded by 32 human skulls—that might be the key to the recent deaths and disappearances at the museum it resides in (Available February 2, 2016).

The Mystery of the Venus Island Fetish by Tim Flannery is set in 1932 and follows young anthropologist Archie Meek and the Great Venus Island Fetish—a ceremonial mask surrounded by 32 human skulls—that might be the key to the recent deaths and disappearances at the museum it resides in (Available February 2, 2016).

It’s 1932, and the Great Venus Island Fetish, a ceremonial mask surrounded by thirty-two human skulls, now resides in a museum in Sydney, Australia. But young anthropologist Archie Meek, recently returned from an extended field trip to Venus Island, has noticed something amiss: a strange discoloration on some of the skulls.

Has someone tampered with the fetish? Is there a link between it and the mysterious disappearance of Cecil Polkinghorne, curator of archaeology? And how did Eric Sopwith, retired mollusks expert, die in the museum’s storeroom? Could Archie’s life be at risk as well?

But these are not the only concerns that weigh upon the assistant curator’s mind. Why hasn’t his beloved Beatrice―registrar, anthropology―accepted his proposal of marriage and the love token he brought back from Venus Island? Has something been lost in translation?

Chapter 1

Archibald Meek watched from the canoe as the muscular form of his adopted brother Cletus dived through the water, coming to rest atop a submerged coral bommie. Cletus stilled momentarily, then thrust his arm into a hidden cavity. A black cloud erupted, leaving only the man’s legs visible. Agame. The giant Pacific octopus. Archie’s eyes followed Cletus as he swam to the surface, the beast’s tentacles waving wildly.

Cletus bit into the animal’s head as he broke the surface, then flipped the lifeless mass into the canoe and catapulted himself aboard. Then he froze. For a moment Archie thought he’d glimpsed the great hammerhead shark that had been hunting the lagoon of late. It was longer than Cletus’ canoe and it moved hypnotically, as if to the throb of an invisible kundu drum—seeing all, sensing all. But it was not that. Cletus pointed with his lips. On the western horizon was the faintest of black streaks.

How long since a steamer last anchored in the lagoon? Long enough that Archie had begun to feel that steamers were things you saw only in dreams.

He had been living outside time, at least as it is measured by clocks and calendars, for almost five years. But that smudge of smoke announced that a ship was coming to restore him to a land where time is doled out in precise units.

The canoe ground into the sand and Archie leapt ashore. He ran to the beach-side hut that he called home. Crates filled with pickled fish, birds and lizards occupied one wall, while from the thatched roof hung all sorts of artefacts, from grass skirts to spears and knobkerries. He sat on his ribbed, wooden sea-trunk, its rusty lock long untouched, and remembered the day he’d arrived.

Then, as today, Archie sat on the trunk. It was midday, and the sun beat down on the deserted beach like a hammer. The sailors remained silent as they offloaded his cargo of preserving jars, reference books and butterfly nets. He had told them what he had half-convinced himself was true: that museum anthropologists had studied and collected on most of the islands of the Pacific, and that very few had come to harm. But the sailors’ eyes said it all: they were sure they were leaving the young scientist to be killed, and most likely eaten, by savages.

As he watched the crew row back to the schooner he erected an umbrella, and waited. Soon, the sounds of the wind in the palms and the chirruping of insects filled his consciousness. As the sun was sinking into the lagoon a man strode out of the shadows, took his hand, and led him to the hut he sat in. Months later Archie learned how lucky he’d been. By sitting and waiting on the beach until being welcomed by the village chief, a man called Sangoma, he’d unwittingly followed protocol, and had been accepted into the clan.

But God, how difficult those first months had been! Archie was as useless as an infant. No, worse. He had the mind of an infant, but the body of a man. He could not light a fire or prepare food. In fact he could hardly tell what was edible and what was not. He unwittingly stole fruit from people’s trees because he did not know that the forest was owned. He transgressed into the women’s menstrual huts and stomped through sacred sites, simply because he did not recognise the many warning signs placed around them. He killed tabooed creatures, defecated in taro gardens (which he took to be the bush), and generally made a nuisance of himself. All the while, Sangoma had made excuses for him, paid compensation to those wronged, and explained that Archie knew as little about life as a child, or a savage.

At first his only use was as a beast of burden—to carry firewood and suchlike. But he was soon participating in communal activities. One morning the men of the village set out to clear the bush for a new garden. Archie swung his axe until he was in a lather of sweat. When the tree he was hacking at finally fell, a great rat slithered out of a knothole in its trunk, and Cletus expertly flung a stick after it, striking it on the head. Archie scrambled to collect the animal, thinking that it might interest his friend and curator of mammals at the museum, Courtenay Dithers. Cletus’ younger brother Polycarp had mimed that the creature was unclean, but Archie persisted in carrying it back to his hut and pickling it. For weeks afterwards, whenever they met, Polycarp would repeat the mime and walk off laughing.

Ever so slowly, Archie had grown proficient at things. He loved fishing best of all because the hooks and line he had brought, along with the experience of a childhood spent fishing around Sydney Harbour, made him moderately competent. But he could not manage a canoe, so needed someone to come with him. It was during his hours fishing, most often with Cletus, that he made most progress with the language.

As Archie realised how ignorant he’d been, he suffered agonies of embarrassment. When he felt competent enough to speak, he decided to broach a subject that he felt might gain him some kudos: the Great Venus Island Fetish, as the mask was known among anthropologists, was the work of a stone-age genius and quite the most famous Pacific Islands artefact in the world. The size of a dinner table, it took the form of a monstrous and stylised heart-shaped face, around the margin of which were attached thirty-two human skulls. It had been taken from the Venus Islands in 1893 by the crew of HMAS Adelaide, during a punitive raid in reprisal for the massacre of the passengers and crew of the Venus. Its loss had been more devastating to the islanders than the shelling of their village, or the destruction of their gardens. Archie was familiar with the fetish because it was a prized exhibit at the museum where he was employed.

Before its removal to Sydney, the fetish had resided on a deserted sandy islet—one of the five islands that made up the Venus Group. Only under the most exceptional of circumstances would the most senior men dare to visit it. To them, the mask was the embodiment of pure evil. Remove just one skull from the cordon of thirty-two sacrificial heads that surrounded the ghastly face, it was said, and the door to an age of depravity, madness and murder would open.

‘Do you remember the great mask?’ Archie asked Sangoma one day as the chief worked carving out a canoe.

Sangoma put down his adze, fixed Archie with a fierce gaze, and said, ‘Such things must never be spoken of while we work. Wait for the story time.’

That night, as the coals died down and the young men drifted off to sleep, Sangoma and a few of the village elders refilled the yangona bowl, and began to whisper about the great mask. They told of its creation by a mad genius who was eaten by an enormous shark on the very day he completed his work. Only the spirits of warriors, which resided in their skulls, would be strong enough to contain its malignant power. But how difficult it was to get those skulls! The Venusians were few, and their enemies too fierce and numerous to make easy victims. So the islanders had lived for years in terror while the protective skull fence was in the making. Then, one day, a godsend came to them. A floating island, full of white-skinned warriors, had run aground during a storm and the survivors had straggled ashore. Exhausted, they seemed to give themselves willingly to the bamboo knife and man-catcher. In a single day the skull fence was completed, and the villagers slept soundly for the first time in years.

‘I know the fetish. I look after it now.’ Archie had boasted in the silence that followed. Eyes flashed in the darkness. Then all the elders started whispering at once.

‘It survives!’ Archie heard. ‘But where? Where is it?’

‘In my village. Sydney.’

From that day on Archie was treated with new respect. Old men took him under their tutelage. Things were shown to him that were revealed only to youths of great promise. One morning, an elder asked what his tattoo should be. Archie was not sure he wanted a tattoo, but sensed that his choice would be significant. Just then a platoon of frigate birds cruised past. Black and red, bent of wing and forked of tail, the enormous creatures flew in a strict V-formation, like some piratical, futuristic flying machines. ‘Alaba. The frigate bird.’ Archie replied. Only later did he consider the possibility that the old man had waited until he saw the birds approaching before asking his question. The tattooing had been painful, but afterwards Archie looked with pride at the image of the bird decorating his forearm, knowing that it was Sangoma’s clan symbol.

At some moment he found hard to identify, Archie stopped collecting things, and practically stopped making field notes. He had slipped from being the observing outsider to one of the clan. It was only as the final stage of his initiation approached that he took up his journal again. He had both personal and professional reasons to record the event. Circumcision had seemed a high price to pay to hear the sacred stories that were essential to his full comprehension of the culture. But after a few swigs of yangona the cut of the bamboo knife hadn’t been as painful as he’d anticipated. As Archie watched his blood drip onto the sand, Uncle Sangoma told him that he was now a man, and a true Venus Islander.

After the ceremony, Archie, Cletus and the other lads had stretched their foreskins into discs, which dried to a parchment. As was the custom, they then tattooed them with their totems. Archie’s frigate bird was beautifully executed. No proposal of marriage would be taken seriously in the Venus Islands unless a man presented his girl with a tattooed, parchment-like disc made from his foreskin. The youths whispered that the objects were infallible love charms. If a girl received one, she would be powerless to refuse the giver anything. She would signal her acceptance of the marriage by softening the parchment in coconut oil, rolling it into a ring, and wearing it on her finger.

The Venus Islands had made Archie a man in more ways than one. He had learned how to carve a canoe and make a bow and arrow. He could catch a tuna or a wallaby as adeptly as anyone. And he had seen five yam festivals, with their moonlit nights of lovemaking and fertility rituals. He was now a man of consequence among the islands. A man in his prime.

Archie’s meditations were broken by a bugling sound. Sangoma was blowing his shell trumpet, his muscular chest rising and falling with the effort. He was magnificent, with his prominent nose, dark eyes and full, greying beard exuding authority.

‘Launch the great war canoe! Launch the war canoe,’ he shouted between notes. ‘Load it as well. Load it with Aciballie’s cargo. All the cargo!’

Cletus, Polycarp and the other lads were already at the door, ready to carry Archie’s crates to the beach. Outside, Archie could see that preparations were being made to launch the canoe he had purchased. As the boys puffed past with boxes and chests, Cletus mimed that he was carrying an extraordinarily heavy crate, and quipped, ‘I don’t know why you bothered collecting all those poisonous and useless creatures, Aciballe. They’ll break my back!’

Archie grinned and covered his nakedness with a bark lap-lap. Then he dashed out the door. He was headed towards the yam gardens, his bare feet beating a frantic tattoo on the burning sand. Round one last corner and he saw her. She was bent almost double, and with each thrust of the yam-stick her withered breasts flapped against her chest.

‘Auntie Balum,’ he cried as he saw the woman who had cared for him as tenderly as any mother could. Balum stretched upright, one hand in the small of her back while she steadied herself with the stick. She’d been a beauty in her youth. Even now her almond eyes, delicate nose and shapely mouth were arresting. For a few moments her tattooed face remained blank, as if she couldn’t understand why he was there. But then her sweet visage collapsed with grief.

‘My son. My son is gone,’ she wailed. ‘My son is gone, gone from my sight!’

It was the traditional dirge for a young man slain in battle.

‘Auntie. I must go home. I told you that when I first arrived. But I will be back.’ Archie’s eyes filled with tears as he cradled her slight body in his arms. He knew he was lying.

An hour later the steamer was inside the lagoon. It was time for Archie to go. He was desperately sad to be leaving his island family. It felt like a sort of death. But if he didn’t leave now he would never see his fiancée Beatrice again. He had written to her at every opportunity. Letters had piled up waiting for a passing vessel. And she had written back. He imagined her beautiful face concentrating as she crafted each sentence, her glorious blonde locks flowing over her shoulders, her exquisite hands delicately holding her pen. And with every loving letter he’d received from her, his confidence had grown. In his last missive, sent by canoe and then native runner to the nearby mission, he had proposed marriage. He felt certain of a positive response. But just to be doubly sure he had enclosed his foreskin love-token with the letter. And now, in just a few weeks, he would fall into her arms, and a new life would begin.

‘Get yer arse aboard!’ the bosun screamed above the creak of the windlass. ‘The fuckin’ tide’s turned. If we don’t shift now we’ll be spending the night with the bloody cannibals!’

The island lads were warily clambering up the rope ladders slung over the side of the SS Mokambo, somehow balancing Archie’s crates on their shoulders as they went. At the rail, equally wary sailors took the crates aboard. The great war canoe had already been winched out of the water. As Archie climbed a rope boarding ladder its outrigger swung wildly, threatening to knock him back into the water. There was no time to say goodbye. He barely had time to wave before he heard the shout ‘up anchor’, and the tramp steamer began moving, leaving the cluster of outriggers and their forlorn paddlers in its wake.

By dusk Great Venus was a mere smear on the horizon, and West Venus Atoll, home of the famous fetish, was close a-starboard. In the gloaming Archie could just about make out the ceremonial path, lined with the ochred valves of giant clam shells, leading in from the beach. There was not a light to be seen on the place: the Venus Islanders would rather die than set foot there after dark.

The last of the tropical twilight faded, and Archie went to his cabin. A small mirror hung on one wall. What he saw in it shocked him: a brown man, muscular, trim and tattooed, dressed in nothing but a skimpy loincloth. The trunk containing his clothes had been placed beside his bunk. He opened it for the first time in years, took out his suit, felt its fabric, and at once remembered his nickname—Beanpole Meek. That, and his brothers’ habit of pointing out his ‘Bondi chest’ (far from Manly) had been perpetual humiliations.

Archie dropped his loincloth and struggled into his trousers. He tugged at them and heard a ripping sound. His right thigh had burst through the seams. Next he struggled into his shirt. It seemed to belong to a child. Surely a fellow couldn’t change that much between nineteen and twenty-four? Perhaps the fabric had shrunk. In any case, the captain’s wife might be able to help.

‘I can put gussets in them, but there’s not a lot of spare fabric, she said dubiously. Her gaze drifted from Archie’s body to the suit and shirt lying in her lap.

‘Do you think you could try? I mean, I can’t arrive home looking like this.’

‘You’re not too hard on the eyes. But I suppose you’ll need clothes in the city. Leave it with me. I’ll fix up something.’

The captain invited his passenger to dine with him most evenings. Archie was surprised at how difficult he found it to have a conversation. He just couldn’t find the words he wanted—in English at least. The captain seemed taken with a young cricketer called Bradman. Even though Archie followed cricket keenly, the name meant nothing to him. And both the captain and his wife kept talking about ‘the crash’. He assumed they were referring to some terrible rail tragedy, until it became clear that it was about money. Lots of money.

Ten days later, with Archie only dimly aware of changes in the wider world, the Mokambo steamed into Sydney Harbour. She passed through the heads in the dead of night, and the first Archie knew of being home—if that’s indeed where he was—was the stench of coal smoke. He sat on deck in the predawn darkness, observing the city lights through the grimy atmosphere.

It had been, he recalled, Professor Radcliffe-Brown who’d encouraged him to go to the Venus Isles. He had the ear of both the museum’s director, Dr Vere Griffon, and Cecil Polkinghorne, the museum’s anthropologist, to whom Archie had been apprenticed. And so, just four years after having arrived at the museum as a fifteen-year-old cadet, Archie was granted study leave to go to the islands.

The Venus Isles had a bad reputation. But in 1911 the Reverend E. Gordon-Smythe had brought Christ to the natives, and it was generally believed that headhunting had been curbed, if not entirely eliminated. Most families would have been concerned to see their son shipping for such a place, but the Meeks were a hard, unsympathetic people. He couldn’t remember hearing a kind farewell from his parents, or from his four brothers.

‘Study the culture, Archie. Note everything, and bring a rational, detached mind to your work,’ Radcliffe-Brown advised. It only now dawned on Archie that, instead, he’d lived the culture. But he had done one important thing. He’d made a collection. And what a collection it was!

Copyright © 2016 Tim Flannery.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Tim Flannery is a scientist, explorer, conservationist, and author of several works of non-fiction, including The Future Eaters and international bestseller The Weather Makers. A regular contributor to The New York Review of Books and The Times Literary Supplement, he also contributes to ABC Radio, NPR, and the BBC. He is the former director of the South Australian Museum and is currently a professor at Sydney's Macquarie University.