He had his forbearers in the field of private investigation, of course. Sherlock Holmes is the standard by which all crimefighters are judged, and Holmes himself had his roots in Edgar Allan Poe’s stories about the Chevalier C. Auguste Dupin. Chandler was directly inspired by Dashiell Hammet’s stories about the Continental Op and Sam Spade. “Hammet,” Chandler famously said, “took murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley.” It was Chandler himself, however, who combined the elements of the classic private eye into its purest form: Philip Marlowe.

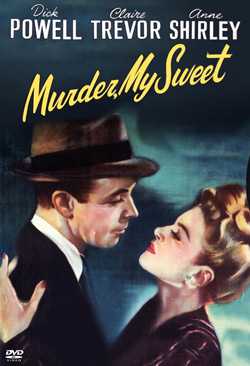

Marlowe proved too good for the folks in Hollywood to resist, though as it had with Sam Spade, it too them a few tries before they got it right. The Falcon Takes Over (also known as The Falcon Steps Out) appeared in 1942 and loosely adapted the Marlowe novel Farewell, My Lovely in order to squeeze out another installment in the George Sanders “Falcon” series. Likewise, Twentieth Century Fox used the Marlowe book The High Window as the basis for the final installment of “Michael Shayne” mystery series starring Lloyd Nolan.

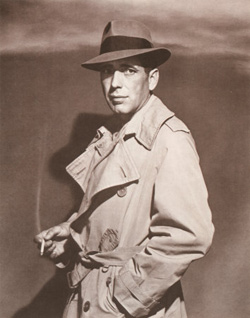

Leave it to Howard Hawks and Humphrey Bogart to make Marlowe into an icon. Bogart had already done his immortal turn as Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon, and in a way his performance as Marlowe in 1946’s The Big Sleep seemed like something of a sequel. In truth, it was produced to follow up another Bogart gem, To Have And Have Not, and to cash in on Bogie’s new romantic partnership with Lauren Bacall.

It wouldn’t be the detective’s last trip to the screen, though, not by far. The following year, Robert Montgomery brought Marlowe to the screen in the bizarre subjective camera experiment, Lady In The Lake. The director/star started with an audacious idea, he would adopt the novel’s first person narrative. Not only would Marlowe (played by Montgomery) narrate the movie, we would see it through his eyes. Aside from a few quick sequences when he is onscreen addressing the audience directly (at the beginning of the film, near the middle, and then again at the end), we would see Marlowe only in fleeting glimpses in mirrors. The rest of the time he would be offscreen while the other actors talked directly to the camera. Give Montgomery points for daring, but he managed to prove only one thing: shooting an entire feature film this way is a terrible idea.

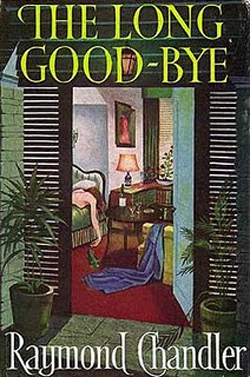

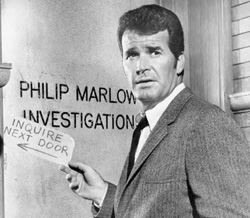

After George Montgomery’s weak turn as the private eye in 1947’s The Brasher Doubloon (a more faithful reworking of The High Window), Marlowe conceded ground to his more violent successors in the fifties. Compared to Spillane’s flag-and-dick-waving he-men, Chandler’s lonely, monastic Marlowe seemed tame. He showed up on television occasionally: Zachary Scott played him in an adaptation of The Big Sleep for Robert Montgomery Presents and Dick Powell took up the role again in a production of The Long Goodbye for the show Climax Mystery Theater. Phil Carey starred in a short lived series called simply Philip Marlowe.

HBO tried a series with Philip Marlowe, Private Eye in the eighties with Powers Booth. The results, while much applauded, didn’t lead to a resurgence in the character. HBO took another shot at Marlowe a decade later when it launched an adaptation of Poodle Springs, based on an unfinished book by Chandler (completed by Robert B. Parker). With James Caan sleepwalking his way through the role, the film didn’t exactly stir up any enthusiasm for a new Marlowe.

Which, of course, isn’t to say that he won’t be back. Clive Owen and Frank Miller were onboard at Universal Pictures a few years ago to revive the character in, reportedly, an adaptation of the story collection Trouble Is My Business. Whether or not this long gestating project ever sees the light of day is ultimately inconsequential. Marlowe is a classic, and classics have a way of coming back around again in one form or another.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor

I love Marlowe, of course, but find Dick Powell’s iteration of him just…lame. I know it suffers from having seen Bogart first, but his acting feels so smarmy, and to me, that’s not Marlowe at all.

I’ve read that they had to sanitize The Big Sleep for the movies, so much so that no-one–not even Chandler–was sure who had done what by the end.

Ah, smarm. The Powell speciality.

As for The Big Sleep, I know when I’ve shown to friends that I usually have to explain the gay sex and pornography angles in the book that have been whitewashed out of the movie.