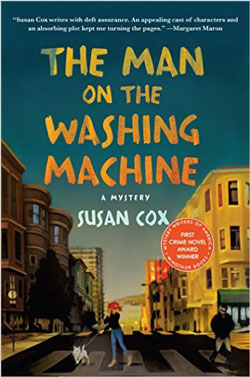

The Man on the Washing Machine by Susan Cox is a debut crime novel about Theophania Bogart, a former Englishwoman who flees to San Francisco and gets caught up in a smuggling operation and a series of murders, who has to race to find the killer before they find her (Available December 15, 2015).

The Man on the Washing Machine by Susan Cox is a debut crime novel about Theophania Bogart, a former Englishwoman who flees to San Francisco and gets caught up in a smuggling operation and a series of murders, who has to race to find the killer before they find her (Available December 15, 2015).

When former party girl and society photographer Theophania Bogart flees to San Francisco to escape a high-profile family tragedy, a series of murders drags her unwillingly out of hiding. In no time at all she discovers she's been providing cover for a sophisticated smuggling operation, she starts to fall for an untrustworthy stranger, and she's knocked out, tied up and imprisoned. The police are sure she's lying. The smugglers are sure she knows too much. Her friends? They aren't sure what to believe.

The body count is rising and Theo struggles to find the killer before she's the next victim or her new life is exposed as an elaborate fraud. But the more deeply entangled she becomes, the more her investigation is complicated by her best friend, who is one of her prime suspects; her young protégé, who may or may not have a juvie record; her stern and unyielding grandfather, who exposes an unexpected soft center; and the man on her washing machine, who isn't quite what he appears, either.

Chapter One

Nothing was different about the Wednesday morning Tim Callahan died. Tim was a petty thief and a bully. I can’t think of anyone who’ll miss him, but being thrown out of a three-story window seems like more punishment than he deserved.

When I woke up, fog was obscuring my slice of Golden Gate Bridge view but sun was expected later, which is fairly typical. I pulled on jeans after a quick shower, and gathered my emotional resources to face another day of lying to every single person I knew. The effort took a toll I hadn’t considered when I moved here eighteen months ago. All the same, for no particular reason I was feeling more hopeful that morning than I’d been for a long time. The dim sum aroma from Hang Chow’s down the block was more appealing; the air a little crisper; colors a little brighter. If I’d been less absorbed with how my friends would react if they found out the truth, I might have wondered what the hell was wrong with me.

I walked down to Helga’s coffee shop and strolled back with my morning tea. The climbing rose was doing its best to obscure the front window of my fancy little bath and body shop, and I made a mental note to have Davie trim it back. He’d turned a corner since he tried to rob me the first week we were in business and, somehow, he never left. We gave him a fifteenth birthday party last month. The rose needed attention, but the planter had been repaired and the whole building painted just after I bought it so it looked good on the outside, even if my top-floor flat was still in the throes of an endless renovation. My tenant in the middle apartment was good at handyman stuff, so his place was nicer than mine at the moment. A friend of a friend was about to move into the ground-floor studio apartment and then I’d have a full house.

Like the British Royals I live over the shop, and I climbed the two flights of stairs to my flat, still thinking about the rose because it was easier than facing other things. Lucy, a burdensome representative of her short, bad-tempered canine gene pool, lumbered out from the bedroom to welcome me back. She realized I was carrying a muffin instead of Milk-Bones, gave me a disillusioned look, and went back to the bed we shared. Until a couple of days ago we’d slept on the Murphy bed in the studio behind the garage rather than risk brain damage upstairs from the fumes of paint and glue. Finding the new tenant meant I’d have to risk it, and besides, I was fed up with sleeping downstairs and commuting up here to my small selection of identical jeans and T-shirts. A couple of days before I’d had a mattress delivered and dropped on the floor of my bedroom. Lucy and I were both more comfortable and I could stop worrying that the Murphy bed mechanism in the studio would fail somehow and stuff us, still sleeping, into the wall cavity. I know—never going to happen. But irrational fears are irrational by nature, right? In any event, I hoped my new tenant had no Murphy bed issues. I liked the view much better from up here, and if I kept the windows open the fumes weren’t too bad.

I wandered back through the mostly unfurnished flat, picking my way through the jungle of timber propped against the walls and the coils of electrical cable littering the floor. The building trembled as it does every now and again. Minor earthquakes can be shrugged off after you’ve lived here for a while. The first few raise your heartbeat a little. The ever-present threat of a big killer shake had added to the renovation costs because shear walls and foundation bolts don’t come cheap. Even so, the result was a priceless refuge from my former life. So far, no one from my Maserati and Bollinger days had come looking for me behind the counter of a small neighborhood store five thousand miles from home.

I could hear Davie shuffling around in the tiny yard behind the shop and the vigorous swishing of a broom. I leaned out of the window and saw the top of his closely cropped head balanced on his thick body like a basketball. By some instinct he looked up and caught sight of me. “Hey, Theo,” he called in his foghorn voice, “you need me up there?”

I shook my head and he went back to his sweeping. I’m not particularly maternal (that’s English understatement right there), but I make sure he does his homework and try to feed him a healthy meal occasionally. Some of his pals have done time in juvie; I’m reasonably sure Davie hasn’t.

I finished my muffin and sipped my tea looking down from my bedroom window at the leafy pocket park that occupies the combined property behind all the buildings on our block and reminds me of my home in England. San Francisco is great in a lot of ways, but I still get homesick sometimes. The way the residents tell it, the landscape has survived nearly a century of volunteer caretaker-gardeners with different and often opposing views of how the space should be used. Pine-needle pathways meander in random directions. Benches and strategic clusters of Adirondack chairs provide places to relax, read, or doze. There are several areas of lawn, a koi pond, some lush perennial borders, and a ruthlessly disciplined knot garden the kids use as a maze and the adults use as a meditation labyrinth. A large compost pile and a toolshed share the blue-collar end of the garden with the ragged abundance of a raised-bed vegetable garden. One of the swings in the cedarwood jungle gym was still rocking gently from the effect of the earthquake.

I was turning away when a flash of movement caught my eye in one of the third-floor windows opposite and very quickly something landed with an abrupt and repulsive thud on the lawn near the children’s swings. I squeezed my eyes shut for a second, certain I must have imagined it. But when I opened them he was still there—a man dressed entirely in white, crumpled on the neatly shaved green lawn with his arms and legs arranged around him like a swastika.

Chapter Two

I called 911 while I was tripping and stumbling down the back stairs and across the garden. Others were running toward the same awful rendezvous. A few of us arrived more or less together, breathless and stunned into silence.

It was hard to look at. With his painter’s overalls gradually soaking up epaulets of deep red, Tim Callahan’s crumpled corpse glowed like graffiti on the green velvet lawn. As usual his chin bristled with a three-day stubble, his truculent expression replaced by a slack-jawed, wide-eyed stare. Given his crushed skull—I looked away quickly—I didn’t expect him to be breathing, but the absence of the life signal that gently raises and lowers the chest in a living being was deeply unnerving. The only things moving in the lifeless tableau that had been Tim Callahan were the tufts of wood shavings stuck to his hands and the front of his overalls. They quivered in the breeze.

Davie stood next to Tim’s body like a postmodernist Colossus, still holding the broom in one huge hand, looking as if his face might crumple into tears at any moment.

“Davie, you should go inside,” I said.

“You might need me.” Then he reached out a big hand and patted my arm. He’s built like a UPS truck and wears an earring in his nose, but he’s still only a kid and he was asking for reassurance, not giving it. I rubbed his hand gently.

I didn’t know what to do. Should I be feeling Tim’s neck for a pulse? There didn’t seem much point given the unnatural angle of his neck. I was saved from having to touch Tim’s broken body when Kurt Talbot—Doctor Kurt Talbot—pushed Davie aside with an irritable shove. He eased the knees of his Armani slacks before crouching to touch those sensitive fingers of his under Tim’s jawbone. After half a minute or so he leaned back on his heels and shook his head. He glanced over at me with an expression I refused to recognize as concern, but neither of us said anything. I don’t remember noticing during our brief affair that Kurt’s winter-cloud eyes are a bit too close together. Maybe I’d forgotten. He’s good-looking if you like the Nordic Snow Prince look, and unattached surgeons are thin on the ground so he doesn’t usually lack for company. Unfortunately he has a lump of ice instead of a heart and no woman has been brave enough yet to risk frostbite on a permanent basis. I think shrinks call that transference: remembering how little Kurt and I meant to each other stopped me thinking too much about the awful sight in front of my eyes. Or maybe it’s called something else. Either way, that’s what I was doing.

Helga, who owned the bakery coffee shop a few doors down from me, came up to us and covered Tim’s body with an afghan of brightly colored squares before anyone could stop her. It immediately started soaking up blood, which made things worse somehow.

“What happened?” she whispered.

Helga was a big woman—a voluptuous, curvy goddess in bakery whites—with golden hair and a fondness for bright pink and leopard-print Crocs. She was looking a little shaky, so I took her hand and squeezed her fingers gently as I shrugged the universal I-have-no-clue shrug. We weren’t close friends, but we’d spent some early morning hours together in the past couple of weeks. Her father had recently died and I was one of a handful of neighbors who’d taken turns playing baker’s helper to give her a bit of a break. She and her dad had been close and his death had hit hard. It had taken me a while to get used to it, but people looked after one another here, and a few hours of shifting bakery trays and kneading dough before sunrise was the way we did it for Helga.

“Looks like he fell out of number twenty-three. That quake—he must have lost his balance,” Kurt said. After another silent moment had passed, he pulled his phone out of his pocket and began to check his e-mails.

“Seriously?” I said. He slid it back into his pocket without a word. Doctor or no, the man was a tool.

“The earthquake had finished before he fell,” I said. Kurt looked annoyed and, since Helga has a crush on him and tends to follow his lead—more English understatement—she withdrew her hand and looked annoyed at me, too.

Someone opened the padlocked gate to the street and gradually the garden filled with police cruisers, an ambulance, and a huge fire truck, complete with firefighters, police officers, and EMTs. The firefighters and EMTs were okay—sort of cute in fact—but I had a bad experience once with police and I don’t like them. Well, it’s more that they scare the hell out of me. An English policeman broke my nose—they’re not all as polite as everyone thinks—and American police are armed. With guns. My muscles tensed and my weight shifted as my subconscious clicked into flight mode and prepared me to back away. I ignored my very sensible subconscious, took a deep breath instead, stayed still, and faced them all down, feeling valiant. They didn’t appear to notice.

We were kept isolated as the bustle and activity level grew, and our little group grew more talkative in a disjointed sort of way, but the conversation was no more illuminating. I was the only one who’d seen any part of Tim’s fall; everyone else had only heard his scream. Helga muttered, “Poor Tim, huh?” at Kurt, who put on his sympathetic doctor face and nodded. I thought he might put a comforting arm around her but he didn’t.

I knew something about Tim—he had put up drywall in my garage and stolen a pair of my mother’s earrings, and he’d once struck Davie in the face and drawn blood. So not feeling too sorry, no. Shocked, but not particularly sorry.

Sabina D’Allessio bit her bottom lip and put an arm around Helga’s shoulder. Sabina was a messenger—she rode a poison-green Kawasaki and hid her mane of springy red curls under a matching motorcycle helmet. I could see she was choking down a giggle and I was afraid to catch her eye since the situation was so dire. She tends to react to pressure that way. She was famous for giggling through her cousin’s funeral and it didn’t take much to set her off. I couldn’t imagine anyone would appreciate it.

Paramedics bundled the afghan out of the way and were working over Tim. The five of us moved away a few yards, keeping together like a school of minnows.

“I hope the homeowners association isn’t liable,” Kurt said abruptly. He pays huge malpractice premiums and tends to worry about things that never occur to anyone else. “If it was the earthquake, it’s an act of God and we’re not responsible.”

“The earthquake was over by then,” I said again.

Kurt frowned and then his expression cleared. “Are you feeling okay? It must have been a shock.” He reached out a hand toward my cheek and I saw Helga’s scowl out of the corner of my eye.

“I didn’t see much of anything.” I jerked my head a couple of inches so his fingers brushed the side of my hair. That had nothing to do with Helga.

“Good. You don’t need more nightmares,” he muttered, and dropped his hand. He was making nice and I felt a little bad for being a bitch. He used to hold me when I woke up from my nightmares. I was starting to get used to it when he ended things. He said I was emotionally unavailable, which was almost funny coming from him, but he didn’t know the half of it.

“I’m fine,” I said, and tried to unclench my jaw and smile at the same time. I was successful enough that Helga scowled at me again.

“Does Tim have a paintbrush?” Davie said. He looked worried, as he often does, but it was the most intelligent remark I’d heard so far. Where was Tim’s paintbrush? His white overalls were smeared with blue and yellow paint and so were his hands—it was fresh, because the wood shavings were sticking to it. If he’d fallen while he was painting a window frame or something, the paintbrush would be somewhere near him on the ground. Wouldn’t it?

“What the hell does that matter?” That was more like the Kurt I knew. Davie looked hurt and I tucked his arm under mine. I’m only eleven or so years older than he is but I swear sometimes I feel like a hen with one enormous chick.

The knot of uniforms nearest to us parted in a lazy wave around a new arrival, a woman with deep, depressed-looking lines from her nose to the corners of her mouth. I guessed she was in her late forties, although she might have been younger and aged by what she’d seen on the job. Her round shoulders were hunched inside a red wool jacket and one was supporting a heavy Coach shoulder bag. She had nut-brown hair cut, apparently, with hedge shears and her expensive-looking glasses were faintly shaded. As she approached us, some instinct made the hairs on my arms ripple like the fur of a defensive dog.

She showed us a badge and introduced herself as Inspector Lichlyter, pronouncing it “lick-lighter,” which struck Davie as funny for some reason. He sniggered and she gave him a look sharp enough to bore a hole in plate steel. See? I was right about the giggling. Davie’s fingers closed more tightly around my arm and he took a half step closer to me.

She rummaged in her shoulder bag for a few minutes and came up with a notebook crammed with folded pieces of paper and used envelopes. She glanced at a couple of the folded notes, found a pen after another rummage, and finally looked up at us. Her shaded glasses reflected the light and prevented me from seeing her eyes.

“Did anyone see him fall?” she said.

No one answered her. I hesitated and watched everyone’s eyes drift to the two paramedics kneeling next to Tim, the urgency gone from their movements. Inspector Lichlyter sighed heavily and shifted her shoulder bag.

“Pay attention, people,” she said more sharply. “Did anyone see him fall?”

“I did,” I said after another moment. She prodded the bridge of her glasses and turned in my direction. She made me uneasy. More uneasy. An inspector in San Francisco is the same rank as a detective in other cities—in other words not someone you would expect to be gathering initial information at an accident scene.

“And your name?” she said.

“Theo Bogart.” Which was half true.

“Ah. The owner of the soap store.”

“Yes,” I said, and didn’t ask how she knew.

“Did he seem to jump?”

I thought back to the little I had seen before Tim landed. “He fell facing backwards. On his back,” I added when she raised an eyebrow.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes,” I said.

She scribbled in her notebook.

“Where were you when it happened?”

I turned to point at my bedroom window. “Up there. On the third floor.”

“Did you see anyone else with him before he fell?”

“No.”

“Did anyone see you up there?”

That was an odd question. Wasn’t it?

“I called down to Davie.”

She looked at Davie. “So you spoke to Ms. Bogart?” He nodded, his eyes wide, and she returned her attention to me. “Your store opens at ten, doesn’t it? I’d expect you to be there.”

“I don’t open up every morning. What does this have to do with the accident?”

She didn’t answer. She stared up at my bedroom and then at the tall old-fashioned windows of number twenty-three opposite. She scribbled in her notebook again. A few of the envelopes and folded papers fell to the floor and a uniformed officer came over to pick them up. She took them from him absently before continuing: “Do you know the dead man, Ms. uh, Bogart?”

“His name is Tim Callahan. He lives in one of the studio apartments and does odd jobs for anyone who can’t get a proper workman to do the job.” He also made up for his low bids by petty pilfering. I was surprised that anyone who knew him would employ him to do anything. I’d hired him, sight unseen, because my business partner Nicole recommended him. Lichlyter gave me a sharp look and I wondered confusedly if I’d said any of that aloud. She asked for my address.

“You know my store opens at ten, but you don’t know my address?” She waited, pencil poised, eyes on me with the kind of resolution that could wear away mountains. I gave her my address.

She raised her voice slightly. “Did anyone else see anything at all?” She passed an eye over our dispirited group and apparently found us wanting.

“I heard him scream, looked out, and there he was,” Helga said. She glanced over at Kurt and then down at her pink Crocs. Kurt and Sabina said much the same thing. Lichlyter wrote it all down.

Davie shifted his grip on the broom in his hand and gave me a worried look. Lichlyter frowned slightly at the broom, closed her battered notebook, thanked us all with a touch of irony, and went to confer with her colleagues. They stood back respectfully as she joined them. They had everything necessary to record the scene, from iPads and tiny video cameras to laptops, and I wondered why she bothered with the notebook.

They let us leave eventually. Sabina suggested we all go to Helga’s for coffee. I gave her big eyes and she looked away quickly, hiding a smirk with a splutter and a cough. Inviting us all to coffee as if we were some new book club she’d organized earned her some shit later on and she knew it. Kurt left without responding. He smiled absentmindedly at Helga, who watched him walk away. She pulled herself together and she and Sabina headed in the direction of her coffee shop.

Davie had to go to school and I went to Aromas, where Haruto pumped me for details of what he insisted on calling our police grilling. Haruto looked like a hippie Mikado and lived in my middle-floor apartment. He’d been working for me a couple of days a week in the store. Before I went inside I heard Lichlyter’s harsh voice tell a uniformed officer to arrange a search for Tim Callahan’s missing paintbrush.

Within hours—gossip traveling at twice the speed of light—we all knew Tim had been hired by a new tenant to paint the inside of number twenty-three. Tim’s paintbrush wasn’t found, although the yellow paint in the attic room had been wet.

Inspector Lichlyter telephoned. She asked me odd questions, as if she was hoping to surprise me into saying something new. I told my bald little story twice more, but it didn’t seem to discourage her. Without knowing why I felt anxious about it, I reminded her that Davie had seen me up on the third floor a couple of minutes before Tim’s accident.

She said: “Ah?” but that was all the reaction I got.

She asked me about Davie, and whether I had definitely seen him in the yard at the time Tim Callahan fell. I insisted, with more emphasis each time she asked, that I had, although in truth there were several minutes between when I saw him and when Tim fell to his death. That’s the horrible thing about police investigations—and believe me, I know. Everything suddenly has grave significance and the difference between “now” and “a few moments ago” feels like an hour. By the time she hung up I was covered in sweat. I couldn’t decide if I should be more worried about Davie or about myself. Before I had time to decide, he climbed heavily up my back stairs.

“Hey, Theo,” he said.

I knew he was nervous about going home, where by this time of night his father would be drinking and waiting to pick a fight.

He sat on the kitchen floor picking at his thumbnails while I heated a couple of cans of chili. Canned chili is Davie’s favorite food. He says his mother used to fix it for him. I sometimes wonder how he grew so big and strong on a childhood diet of canned chili and Dr Pepper. I usually try to feed him some vegetables, but I couldn’t summon the energy to steam broccoli. We ate the stuff with corn tortillas torn into pieces with our fingers. Davie sat on the floor and I perched uncomfortably on an upturned spackle bucket.

“Did she ask you anything else?” Lichlyter had called him, too.

“Sure. She asked if I’d ever argued with Tim. But don’t worry,” he said. “I told her the truth.”

That gave me a jolt on several levels. I thought she would only ask him about what he’d witnessed; she hadn’t asked me much more than that. “You told her you worked for Tim?”

“Yeah. And I told her Tim cheated me and wouldn’t pay me, the asshole.”

My fault—I asked Tim to hire Davie before I noticed the missing earrings. “I remember. Did you—did she ask anything else?”

“I told her Tim and I had a fight and Tim hit me.”

My fault again—Davie got my mother’s earrings back for me. “Did you tell her you didn’t hit him back?”

“Sure. Don’t worry. If I hit him, he wouldn’t get up again.” He grinned.

“Don’t say things like that to her, okay?”

I told him everything would be fine and hoped I wasn’t lying. He hung around helping me shift lumber and drop cloths out of my bedroom until nearly eleven, by which time his father was usually unconscious and Davie could get into their apartment unnoticed. I went to bed and, as usual, didn’t sleep.

* * *

So nothing much was different about the day Tim Callahan died. He was a petty thief and a bully, and I couldn’t think of anyone who would miss him. But it was pretty clear Lichlyter thought he’d been shoved from that third-story window, which meant intense police scrutiny for all of us, which meant our secrets might no longer be our own, which meant my life was going to be even more complicated than it was already.

Copyright © 2015 Susan Cox.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Susan Cox is a former journalist. She has also been marketing and public relations director for a safari park, a fundraiser for non-profit organizations, and the president of the Palm Beach County (Fla.) Attractions Association. She considers herself transcontinental and transatlantic, equally at home in San Francisco and Florida and with a large and boisterous extended family in England. She frequently wears a Starfleet communicator pin, just in case. Her first novel, The Man on the Washing Machine, won the 2014 Minotaur Books/Mystery Writers of America First Crime Novel Competition.