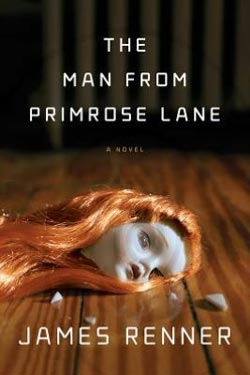

Available March, 2012-

Available March, 2012-

In West Akron, Ohio, there lived a reclusive elderly man who always wore mittens, even in July. He had no friends and no family; all over town, he was known as the Man from Primrose Lane. And on a summer day, someone murdered him.

Fast-forward four years. David Neff, the bestselling author of a true-crime book about an Ohio serial killer, is a broken man after his wife’s inexplicable suicide. When an unexpected visit from an old friend introduces him to the strange mystery of “the man with a thousand mittens,” David decides to investigate. What he finds draws him back into a world he thought he had left behind forever. And the closer David gets to uncovering the true identity of the Man from Primrose Lane, the more he begins to understand the dangerous power of his own obsessions and how they may be connected to the deaths of both the old hermit and his beloved wife.

Prologue

He was mostly known as the Man from Primrose Lane, though sometimes people called him hermit, recluse, or weirdo when they gossiped about him at neighborhood block parties. To Patrolman Tom Sackett, he had always been the Man with a Thousand Mittens.

Sackett called him the Man with a Thousand Mittens because the old hermit always wore woolen mittens, even in the middle of July. He doubted most people had noticed that the old man wore different woolen mittens every time he stepped out of his ramshackle house. Most people who lived in West Akron averted their eyes when they saw him or crossed the street to avoid walking by him. He was odd. And sometimes odd was dangerous. But Sackett, who had grown up just a few houses north of Primrose Lane, had always been intrigued. In a binder somewhere in his basement, alongside boxes of baseball cards and his abandoned coin collection, was a detailed list of each mitten he’d seen the old man wear—black mittens, tan mittens, blue mittens with white piping, white mittens with blue piping, and, once, in the middle of some long-ago May, Christmas mittens with candy canes and reindeer.

On the short drive from the station to the little red house on Primrose Lane, it occurred to Sackett that he had not seen the Man with a Thousand Mittens since the day he had graduated from high school, twelve years ago. He recalled the old man shuffling down Merriman in front of his home, as his mother snapped pictures of his little brother, who had stolen his cap and gown and had stumbled around the lawn buried in maroon and gold rayon. He remembered how excited he had been a few days later, when the strange old man had appeared in a couple of those photos: blurry and distant, but there. As far as he knew, they were the only pictures of the man that existed.

Sackett turned onto Primrose Lane, which was really nothing more than a long driveway, as the Man with a Thousand Mittens was the only person who actually lived on this no-outlet side street. Sitting in the shade of the leaning porch was the young man who had dialed 911. Billy Beachum. He was the only direct contact the old man maintained with the outside world.

Billy Beachum was a delivery boy. Once a week, Billy drove his ’99 Cavalier to the house on Primrose Lane, delivered a box of essentials, and took the list for next week from the old man’s mitten-covered hands. There was rarely any conversation. It was Billy’s job to get everything on the old man’s list, no matter how loony the items seemed to be. He was given a credit card on which to charge the items. It was in the name of a business called Telemachus Ltd., a holding company whose true ownership was hidden behind a labyrinth of legal structures and subsidiaries. Bill was given three hundred dollars a month in cash to keep for his time and troubles—not bad for a sixteen-year-old with nothing but a cell phone and a hand-me-down car to his name.

Billy had inherited this job from his brother, Albert Beachum, who had inherited it from his cousin, Stephen Beachum, who had inherited it from their uncle, Tyler Beachum, who had inherited it from who the hell knows because Tyler’s dead now. Billy was discreet and didn’t talk about his odd job with even his closest friends. He took pride in keeping secret his connection to the Man from Primrose Lane, as he took pride in delivering every item the old man asked for each week, a particularly hard game on the occasions when he asked for things like “a crisscross directory of Cleveland Heights, Ohio,” “a shed cicada skin,” or “a container, roughly ten inches square, that can persist in the elements of Ohio weather for fifty years.” Mostly, though, it was easy stuff—groceries, paperback novels, jerk-off magazines.

The Beachums had kept their involvement secret for nearly thirty years. There was, in fact, only one thing that would permit them to break their silence—and that one thing had, apparently and unfortunately, occurred on Billy’s watch.

“He won’t answer the door,” Billy said, by way of a greeting, as Sackett approached. “I think he might be dead.”

The officer paused and sniffed the wet summer air. A dark tone of rot was unmistakable, though probably too faint for the boy to pick up, or he wouldn’t be sitting so close to the door. Sackett, who had recently recovered the body of a man who jumped off the Y-Bridge, a body that had gone undetected for a week because no one at the homeless shelter had reported him missing, recognized the smell for what it was and felt his stomach lurch at the fresh memory of the maggots he’d found crawling out of the bum’s nostrils, like living boogers.

He looked at the young man, at the grocery bags resting beside him (containing food, a copy of Hustler, the latest Winegardner novel, and a Geiger counter—which had been an extremely challenging request, for as much good as it would do now) and quickly deduced Billy’s role. It explained a lot—how no one ever saw the old man at the convenience store, for example. Of course he had to have had someone running his errands. In a time when many teens text rumors and post salacious half-truths on Facebook, the policeman felt admiration for the young man—and those who had come before him.

He rapped his fist upon the door; a deep, hollow sound. He knocked again, louder. “Police,” Sackett announced in a voice an octave lower than normal.

Billy regarded him with wide eyes but didn’t move.

“Do you have a key?” he asked.

The young man laughed politely.

“I didn’t think so.”

Sackett peered through the misty porthole set in the front door. It was too dark inside to see.

Reflexively, he twisted the doorknob. The glass knob spun unhindered in his hands as the door clicked open with a shudder that seemed to ripple across the entire house. A puff of dust wafted through the narrow slit of dark between the door and the front wall, sprinkling the air with a galaxy of tiny motes. Was that the sound of a gentle sigh? Or was that in Sackett’s mind?

“Holy crow,” said Billy. “I didn’t even try it. Sorry.”

Sackett lifted a hand toward the young man. “Stay here,” he said. “I’ll be right back.”

The house was a twentieth century Tudor, a large cottage-style home, and the front door opened into a narrow foyer. Beyond, Sackett saw steep stairs leading to a second floor. The smell was worse here. Rank and deep.

“Hello?” he said, his voice breaking in the middle like a teenager’s. “Is anyone here?”

To his left was a thin coat closet that smelled of cedar. He knew what was in there even though he’d never stepped inside this house before. He couldn’t help himself. He watched his hand stretch out from his body and pull the door open. Inside were boxes and boxes stamped miscellaneous. The top box was open, revealing an assortment of mittens, in every color of the rainbow. There had to be at least a hundred pairs in there.

By the time he turned back toward the stairs, his eyes had adjusted to the darkness well enough for him to notice the trail of blood leading from around the corner, where he assumed the kitchen was, into the living room a few steps forward and to his left. A body had been dragged across the dusty hardwood floor.

Sackett unsnapped his sidearm but left it hanging loosely at his side as he walked into the living room.

The trail ended at the body of the Man with a Thousand Mittens. The old man sat in a pool of dried blood at the center of the room, propped up against a toppled wooden chair. The only other furniture in the room was a single metal fold-out chair in one corner, beside an old lamp, resting on the floor. Each of the four walls was entirely concealed by stacks of paperback books that stretched to the fourteen-foot-high ceiling in tightly packed and ordered skyscrapers. The dead man’s head rested on his chest, his legs splayed out in either direction. Someone had cut off his fingers.

Sackett leaned toward the body, carefully avoiding the pool of dried crimson surrounding it. The old man was dressed in a stained white T-shirt and khaki shorts. On the shirt was a black hole the size of a dime, a few inches below the sternum—a single bullet hole. Streams of maggots slithered out, landing on the hard film of blood with a sound that could have been a light rain against a window.

That sort of wound, he knew, makes a man bleed inside. Most of the blood on the floor had, no doubt, come from his hands.

Sackett stood and walked deliberately to the kitchen, following the trail of blood to its point of origin. It began at the blender.

“Are those fingers?” asked Billy, eyeing the chunky, mold-crusted contents of the blender from the other doorway. “Oh, God,” he said. The young man heaved once. Twice. On the third heave, a half gallon of vomit shot out of his mouth and onto the floor, tainting Sackett’s crime scene with partially digested ham and cheese Hot Pocket and red Kool- Aid.

“Feel better?” he asked.

Billy nodded.

“Next time someone tells you to wait outside, you think you might listen?”

Billy nodded.

“Good.”

PART ONE: ELIZABETH

Episode 1: The World According to David Neff

David Neff missed a lot of things about his wife, but the thing he missed the most was the way she used to sit on couches, leaning against one giant pillow, her knees tucked up against her chest, her legs trailing behind her as she watched a Lifetime movie or some ridiculous reality show. He pointed out to her once, before she died, that no man ever sits on a couch like that, that it was a uniquely feminine trait. It was a little thing that delighted him. He loved the carefree way she moved her feet to the rhythm of the lights on the screen. When he finally went through her things two months after she was in the ground, he’d found a photograph of her as a child, curled up on her parents’ sofa in the exact manner he remembered. He’d stuck the photo to the refrigerator. It was still there, next to the over-outlined caricature drawings of their four- year-old boy.

Like most Thursday afternoons, David was on the living room floor, in front of the couch—her couch—with a bowl of SpaghettiOs in his lap, a bag of Kettle Chips to his right, watching an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants he’d seen five times, but TiVo’d anyway. The boy, Tanner, napped upstairs.

David was a once-handsome man who had grown pudgy around the edges. His dark hair hung too long above his eyes, a bit too gray for thirty-four. Three-day-old stubble shaded his double chin. A dollop of dried ketchup was smeared across the front of his shirt, evidence of the barely won battle that had been Tanner’s lunch.

The room around David appeared to be the remnants of a livable space that had been torn apart by some sort of laundry- and toy-filled IED. Every other week, Tanner’s great-aunt came by and picked the boy’s clothes off the mantel, lamps, and ceiling fan, laundered them, and returned them, folded, to the boy’s bedroom dresser. She collected the broken robots into dustbins, sorted stuffed frogs and Legos into their assorted tubs, and replaced the batteries in the boy’s plastic-ball shooter and tiny grand piano. It only took them two days to get the room out of order again. David didn’t mind the mess. And neither did Tanner.

Because his wife’s death had been ruled a suicide, her insurance had not paid out and David had not been able to work a single day since. But he and the boy didn’t need the money. Royalties from David’s first book—The Serial Killer’s Protégé—had climbed to the seven-figure mark a couple years ago and sales remained strong, thanks, in part, to a Rolling Stone article that had forever labeled him as “the best true crime writer since Truman Capote.” David no longer kept track of how much he had in the bank, but he knew it was more than he’d ever imagined making in his life.

After his wife’s death and until just a moment from right now, David had resigned himself to the fact that The Serial Killer’s Protégé would also be his only book, and that that was okay, because Tanner was alive and he could live out the remainder of his days keeping his boy safe and comfortable and happy.

But then there was a knock at the front door.

David wasn’t expecting company. Tanner’s aunt wasn’t due for a few days. He assumed it was a neighborhood kid pushing school band–sale candy, so he ignored it. But then the knock came again, too loud to be anything but an adult.

He walked to the door and peered through the porthole. There was a man on his doorstep. A thin man with wire- rim glasses and a ring of hair circling a bald dome.

Paul.

David winced. He didn’t want to see Paul. He didn’t want to talk to Paul. It was Paul’s fault that he wasn’t able to grieve the way he sometimes felt he deserved—in a penniless gutter with other heartbroken souls.

Paul Sheppard was his publisher, the man who had read David’s proposal for a book based on notes left behind by convicted killer Ronil Brune and recognized a modicum of talent. Before The Serial Killer’s Protégé, Paul had been an exclusively local publisher, the sort that shipped glossy copies of Cleveland Steelworker Memories and Cleveland’s Haunted History to local indie bookstores. Today, he kept an office in Manhattan.

Reluctantly, David opened the door.

“He’s alive!” Paul shouted, raising his arms in the air like Dr. Frankenstein.

“Shhhh! You’ll wake the kid,” he said. He motioned for Paul to come in.

“Sorry.” Stepping into the main room, Paul shook his head and whistled. “I saw this documentary on Discovery the other day,” he said. “It was about this woman who lives in Manhattan and she’s this ridiculous pack rat and never throws anything away. She had this path carved out in clutter she could use to get to the bathroom and kitchen.”

“Yeah?” prodded David.

“You’re like this far away from becoming that woman,” he said. “Her family had her committed, you know.”

“Thank God you’re not my family, Paul,” he said, smiling a little. “Don’t sit on that!” He jumped to the recliner over which Paul was squatting and batted away yesterday’s Beacon Journal. Underneath was a plastic dish that had once held a microwavable Salisbury steak dinner. David tossed it to the far corner of the room, where it landed next to a wastebasket. “I wasn’t expecting company.”

“I left you twenty messages. The only reason I knew you weren’t dead is you keep depositing my checks.”

Paul sat on the chair as David collapsed on the sofa, sending a mostly empty biggie-sized soda tumbling to the floor. “It is nice to see you,” David said sincerely. “How’s biz?”

“You know,” said Paul, making a seesaw gesture. “Protégé is still selling. I think half the universities in the country are teaching it in their journalism programs, so that helps it move every semester. I just signed this new up-and-comer from Pittsburgh, whose manuscript knocks me out.”

“It’s not a memoir, is it? Tell me it’s not another memoir.”

“In fact, it is a memoir. It’s about an alcoholic steel smelter who went to prison for grand theft and, when he got out, cleaned himself up by slowly constructing a jet-powered semi truck in his garage. It wouldn’t kill you to blurb it.”

“Is that why you came over?”

“Of course not,” said Paul, a thin smile playing at one corner of his mouth. From his sports jacket pocket, the publisher pulled a bound galley of a book. He tossed it to David, who snatched it out of the air one-handed.

On the front was a grainy black-and-white picture of a grassy hill soaked in summer heat. Atop the hill sat a 1970s-era police cruiser, its driver’s-side door ajar. Behind the car stretched a row of old-growth pine trees, gnarled branches like arthritic hands. David knew this photograph. He’d discovered it, in fact, tucked into a box labeled miscellaneous in the Press archives at Cleveland State. It was a picture of a crime scene, an artifact of one of the many unsolved cases he’d written about before he’d become completely obsessed with Ronil Brune. The title of the book was The Lesser Mysteries of Greater Cleveland. At the bottom was David’s name.

“What’s this?” he asked.

“Your next book,” said Paul. “That’s just a mock- up, but I wanted you to see it, to feel the weight of it in your hands. It’s a good cover, no?”

“It’s a great cover, Paul,” he said. “Only problem is, I didn’t write this.”

“You did. It’s twelve of your best true crime articles from your Independent days, Beverly Jarosz, Sam Sheppard, Lisa Pruett. I cleaned up the language and moved things around a bit here and there—don’t look at me like that, you were still learning dramatic narrative structure back then—and I put them all together into this little trade paperback. Something for next summer’s beach crowd, I’m thinking. Something to tide everyone over until the next David Neff book.”

“I don’t need the money.”

“I don’t, either.”

“Then why?”

Paul glanced around the room, then back at David. “I think you need something to remind you why you were ever a writer in the first place,” said Paul. “A little New England collegiate lecture tour? Some free publicity in the trades? Groupies?”

“True crime groupies are mostly middle-aged women who look like my high school home-ec teacher,” said David. “Nobody wants to buy a bunch of old stories. Anyone who wanted to read them has read them online already.”

“Ah,” said Paul, raising a finger. “They’re not all reprints. Check out the table of contents.”

“ ‘The Curious Case of the Man from Primrose Lane?’ ”

“Your next project,” said Paul. “It’s the next mystery you’re going to investigate, the new piece we’ll use to market the book.”

“The Man from Primrose Lane? Never heard of him. Who is he?”

“Geez, David. Don’t you read the paper anymore?” Paul regarded his friend silently for a moment, studying his features, perhaps to discern if there was any trace of the old David Neff in there someplace. “You used to be the eternal optimist,” he said. “You thought you could solve all of these mysteries, remember?”

“How’d that work out?”

“Are you fucking blind? Look around you. What paid for this house? These toys? The Volkswagen in the garage? Your four- year-old son’s trust fund? You solved the Ronil Brune case. The most fucked-up case anybody ever heard of.”

“I’m just a dad now.”

“Four years is long enough to live in the dark. You told me once that you never felt better than when you were writing these articles and researching these cases. This is a new mystery to dive into.”

“A little ironic, don’t you think?” asked David. “You want to pull me out of my depression by making me investigate some unsolved murder.”

“There’s no dead kids in this one. At least not murdered ones.”

“That you know of.”

“Do you want to hear about it?”

David rubbed his hands together distractedly. Was he already feeling a little rush? His heart stutter-stepped in his chest. His neck itched. Yes, he remembered this well. A jonesing, a craving for something he knew he shouldn’t accept. He imagined it was the way his mother must feel every time she saw a waiter pour a glass of wine in a restaurant. This was what almost ruined his marriage once upon a time. “Yes,” he whispered.

“The Man from Primrose Lane was a recluse who lived on the west side of Akron, only about a mile from here, off Merriman.”

“Right, I know Primrose. Wait. Are you talking about the old man who used to ramble down to the park in the middle of the summer sometimes wearing mittens?”

“I believe so, yes.”

“I saw him a few times after we moved here. Strange dude. Walked like he had somewhere important to go, except I never saw him anywhere except walking. Never at the store or in line for Chinese takeout or stuff like that. Never made eye contact. Gave me the heebie-jeebies. I always thought he looked a little like my Uncle Ira on a bender. He’s dead, I take it.”

“Murdered.”

“How could someone have a grudge against him if he didn’t know anybody? Was it a burglary?”

“Doesn’t look like it. It seems personal. Whoever did it hacked the old man’s fingers off at the second knuckle and fed them into the blender. Sliced his palms to shreds. Then he was dragged into the living room and shot once in the stomach. Killer left him there to die. As much as they can figure, it took maybe a half hour for him to bleed out. The old man was forced to sit there and let it happen.”

“Holy shit. When was this?”

Paul repositioned himself in the chair, suddenly uncomfortable. “They found the man’s body on June twenty-first,” he said. “June twenty-first, 2008.”

“Two days after Elizabeth.”

Paul nodded again.

“No wonder I didn’t hear about it.” David sighed loudly, then shook his head. “Suspects?”

“The police are clueless, and I mean that quite literally.”

“What was the guy’s real name?”

“Well,” said Paul with a smile, “that’s where it gets interesting. When he purchased his house in 1969, he used the Social Security number of a man named Joseph Howard King, but that isn’t who he really was.”

“What do you mean?”

“A year after they find the body, the police get a call from the bank. Turns out this guy had about seven hundred grand in a savings account and another three and a half million in stocks and bonds. Using the name Joseph Howard King, he invested heavily in technology—Apple, Google, stuff like that. But the bank can’t find his next of kin, right? So they call the cops for help. By then, though, the detectives have been working the case for a year and they haven’t found this guy’s family, either. A probate judge gets involved because of the money. I mean, somebody’s going to collect a big paycheck as soon as they figure out who it should go to.”

“That money’s probably the motive,” said David. “Four million dollars means four million reasons to kill him, if you’re an heir.”

“Right. Except no family has come forward to claim it. So this judge appoints a man named Albert Beachum as executor of the estate. Apparently Beachum’s family had been running errands for the Man from Primrose Lane for years. He allows Beachum to draw money from the account to relocate the guy’s remains from his pauper’s grave to a bigger plot in Mount Peace Cemetery. And when Beachum says, ‘Screw the police, I want to hire a private eye to track this man’s family down,’ the judge says, ‘Fine,’ and lets him pay for his own investigator. The PI uses Joseph Howard King’s Social Security number to get his birth certificate. That has the guy’s parents’ names and the name of the hospital where he was born. So the PI goes and pulls the rec ords from the hospital in the years leading up to and following King’s birth.”

“He found Joseph Howard King’s siblings.”

Paul touched his nose with one finger and pointed at David. “Bingo. Another kid named King with the same parents was born two years earlier at the same hospital. It’s the guy’s sister, Carol. So the PI’s really excited, right? He’s about to call this woman up and tell her she just hit the lottery. Except, when he does, Carol tells him that her brother Joe has been dead since 1932. Died in a car crash in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, at the age of six. The crash also killed Mom and Dad. Carol was at home with the babysitter.”

“He stole a dead kid’s ID and disappeared to Akron, Ohio,” said David, his eyes wide and slightly unfocused, the look of a stoner in the afterglow of a good hit. “You know, I bet he came from Bellefonte. He probably read about the accident in the paper and remembered it years later when he needed to change his name for whatever reason. What are they going to do with the money now?”

“Everyone is fighting over it. Carol wants it, of course. Figures since this mystery man stole her brother’s ID she has some right to it. She has a pretty big-time attorney working for her. The Beachums seem like nice people, but they’ve got a hand in this, too, and have retained their own lawyer. On top of that, you have the Summit County executive and the mayor staking claim. Law says if you can’t find next of kin, money goes to the state, but the city and county want a piece of it, too.”

“And the police?”

“The police haven’t said peep. And there’s one more twist to this, just to complicate the picture.”

“Of course there is.”

“Among the old man’s very scant personal effects were a bunch of battered notebooks.”

David leaned forward. “And inside the notebooks?”

“Inside is the life story of a girl he apparently never met, a record of every softball game she played in, every award of merit she won in school, every boyfriend, every minor traffic ticket. All the details of her life were collected in these notebooks in scrawled handwriting they can only assume belongs to the Man from Primrose Lane.”

“He was a stalker, huh?”

“Of the highest degree.”

“And this girl, she’s going after the money, too, I take it?” asked David.

Paul shook his head. “Nope. She couldn’t care less. Which is a shame, because those notebooks are like love letters in places. Obviously, the old man cared a great deal for the girl, sorry, young woman, in his own twisted way. He never names her as his beneficiary, but almost implies . . . well, you’ll have to read the newspaper clippings.”

David sat on the couch, staring into the air above the tele vision. Periodically, he scratched at the stubble on his boyish face. Eventually his eyes settled on a picture of Tanner, resting on the mantel. The boy was about two in the photograph, his shaggy hair whipping about in the wind pulling out over the ocean behind him.

“It’s a good story,” he said at last.

“I know.”

“Sounds like it’s been mostly reported, though.”

Paul waved his hand in the air. “It’s been reported, but it hasn’t been written. And there’s still plenty mystery for you. Who killed him, who he really was, why he was stalking this girl . . .”

“I appreciate what you’re trying to do,” said David. “And if I was ready to start writing again, this would be about the perfect case. But I can’t.”

“Why?”

David stood up and motioned for Paul to follow. “Step into my office,” he said. “Let me buy you a drink.”

David’s home was a sprawling high-ceilinged ranch built for an Akron homeopathic doctor in 1954. The architect had deferred to the bachelor doctor’s sense of style: modernism with a hint of refined hillbilly. Rock gardens sat on either side of the fireplace, used, currently, as rough terrain for a phalanx of plastic army men advancing on the kitchen. The walls lining the long hallway leading off the living room were coated in horse-hair paper, soft to the touch but frayed near the bottom where the previous tenants’ cat had rubbed against it. They passed Tanner’s room quietly. He lay snoozing in the middle of his bed, his knobby knees tucked under him, his butt pointed toward the sky—it was the only way he could sleep. At the end of the hall, through an oak door, was the so-called East Wing of the house.

The East Wing was essentially two rooms connected by a wide threshold. David had converted the entire space into a workroom. Bookshelves lined the walls, many filled beyond capacity, paperbacks stacked three rows deep. Every so often the pattern of books was broken by Star Wars figurines David used for bookends. Han Solo kept a dog-eared copy of The Dubliners from slipping aside. Up front was a bar stocked with Dewar’s, some gin, and a mostly empty bottle of Jameson, a gift from Paul. The fulcrum of the two areas was occupied by a Tron arcade game, which, sadly, no longer worked properly—the laser cars could not be controlled and the contraption had a habit of shocking you whenever you maneuvered your tanks. At the far end of the East Wing was David’s desk, a monstrosity he’d found at an estate sale a week after his book broke The New York Times Top 15. Supposedly it had once belonged to the captain of the Edmund Fitzgerald. David thought it might be cursed. The Edmund Fitzgerald was at the bottom of the lake. His wife was dead. And he hadn’t written a single page since he had paid five men to lug it inside. Mounted above the desk was the head of a brown bear, a curio that had come with the house.

David lifted the front of the bar and stepped behind it. He fished a shot glass out of the cabinet above his head and set it down in front of his publisher. Into the shot glass went the rest of the Jameson.

“Where’s yours?” asked Paul.

“If I drink, I’ll lose my liver,” said David. “I’m up to a hundred and twenty milligrams of Rivertin a day. They tell me that if I drink on that, even a little, it’ll wreck my liver quick. Hell of a side effect, huh?”

Paul blinked behind his glass.

“And I’ve discovered that, to some extent, it was my anxiety that drove my writing. My paranoia. And now I never feel anxious.” David shook his head. “I’ve tried. All that comes out is trite garbage. I can’t write an original simile to save my life. It’s like . . . I dunno . . . it’s like I’m comfortably numb. No more panic attacks, no more night terrors. But no more stories, either. I can’t get to that place. And even if I wanted to come off it, I’d have to do it in stages. My shrink says it would take months to wean myself off the drug. So, when I say I can’t, I mean, physically, I can’t.”

Paul upended the whiskey into his mouth. “Fuck,” he said.

“Yeah.”

A long silence settled in. After a while, the sounds of a child stirring could be heard drifting down the hallway, squeaky springs under gentle weight, low grunts and sniffles. Tanner would be awake soon.

“Look,” said Paul at last, “everything happens—”

“Stop right there. Think about what you’re about to say.”

“There’s a reason to things,” Paul continued. “I mean it. I don’t know why you were attracted to that story that gave you PTSD. But there’s a reason. Gotta be.”

“You can’t say stuff like that to a guy whose wife drove her car into the side of a Dollar General at seventy miles an hour.”

“The only reason you didn’t join her was because you were on the meds. Am I right?”

David ignored him. “The universe is absurd. People want to make sense of it because we’re hardwired to find reason in the randomness. We look for patterns in the chaos. See omens in coincidence. We look at the random distribution of stars in the sky and pretend they look like animals, call them constellations. For some reason, we want to give meaning to the meaningless. If you go looking for the number eighty-eight, you’ll see it everywhere—the number of keys on a piano, the number of counties in Ohio—but it doesn’t mean anything.”

Paul wiped a tear out of his eye. Impossible to tell if it was from laughter or from the sadness he felt for David, who no longer believed, who could no longer even write. “About the constellations,” said Paul.

“I always thought that God put the planet here so we would recognize the artwork He wove into the universe.”

David drew in a breath. He was about to say something more, but then his son spoke from the doorway.

“Dad?” said Tanner. “I’m thirsty. Can I have a Fresca?”

The boy’s head barely reached the doorknob, his dark hair crumpled and slept-upon. His brown eyes looked the size of half dollars below the ragged trim of his bangs. He was a skinny boy, four years old, with long arms and long fingers, piano-playing fingers. He looked more and more like his departed mother every day.

“Think about it,” said Paul. “We’ve got time.”

Episode 2: Sparko’s Tale

When David first met his wife—when David first really met his wife, because they’d been sitting in the same class for five weeks but had never had a conversation and she had never really looked at him, never considered him as a fellow human being—she hated everything about him.

It was at Kent State, in the basement of the music department, in a classroom that smelled of wet chalk dust. The class was Music Appreciation or Music as a World Phenomenon or something. They both forgot in the years that followed. But they both remembered that she really did hate him there for a moment. Him and everything he was about.

“Well?” the professor asked.

They were listening to a CD recording of “Fanfare for the Common Man” piped out of the tinny speakers of the teacher’s stereo. For a moment no one spoke. The students avoided eye contact with their professor, lest they be called upon.

“How does it make you feel?” the professor asked. “What emotion is the composer trying to evoke?”

A suntanned young man in an armless T-shirt, sitting near the back, raised his hand. The professor nodded in his direction. “It makes me think of beef,” the young man said.

Random chatter mixed with the deep sound of laughing approval.

“Right, it’s from that beef commercial,” said the professor. “Anyone else?”

From where he was seated, next to the door, David watched Elizabeth’s face shrink into a scowl, her bottom lip puffing out in a childish, yet sensual, pout. She was waiting for the professor to notice, he knew. He had watched her from this safe corner of the room since their first day of class, hoping to catch her eye in exchange for a smile. But she never turned in his direction. He had memorized the contours of her profile, that bump of an upturned nose, her round ears, attached at the lobe, holding back a cascade of straight hair the color of dying embers. She was, as those Eagles once said, “terminally pretty.” He had come to learn of her endearing idiosyncrasies, least of which was her desire—he assumed subconscious—for admiration and recognition. She finished tests ten minutes before anyone else. When it had been her turn to give a lecture on a major composer, she was the one who had picked John Cage and had actually scolded the poor boob who’d nodded off halfway through her presentation. She had flicked him, hard, on the right ear. But for it all, she was allotted a strange acceptance. David had been standing in the hallway, pretending to rifle through his backpack while he waited for her to pass by one day, and so had been present when the young man whose ear she had struck asked her to a movie. “Forget you,” she had said. David couldn’t stop the silly smile from stretching across his face as he remembered the way she had swished down the hallway without even looking in the jock’s general direction, leaving him stunned and downright weirded out. David lay awake often, wondering what it was about her that he was so drawn to. The only woman he knew who could be so cruel and lovely at the same time was his mother. The mystery of why Elizabeth thought she needed to keep her distance from the rest of the world attracted him. He craved her mystery. On some level, he suspected the search for that answer was more attractive to him than she was. He was smart enough to realize there was some perversion in that.

“Miss O’Donnell?”

“It’s a lie,” she said.

“I don’t follow,” the professor replied.

Elizabeth waved her hand at the stereo as if she were motioning to the place on her carpet where the cat had just barfed. “That,” she said, “is propaganda. Like religion. It’s supposed to create passion in the common man, the blue-collar worker, to push them to serve their country, like to join the Navy or Marines, or even just to keep working those long shifts at Taco Bell. It’s about the illusion of the American Dream.”

David watched the quickening of her breath, the way her chest pumped up and down with anger, the flushing of her face. And suddenly he realized two unpleasant truths. One: this woman was crazy. And two: he was attracted to her in some way he did not understand, and could not control, and didn’t that make him crazy, too?

“The American Dream is a myth,” she continued. “The few who are at the top want us at the bottom to think that we can rise in the ranks through hard work. But that’s just not true. This is like our version of Wagner. It’s twisted. And dangerous.”

“The American Dream is not a myth.” It wasn’t until the entire class—Elizabeth included—turned his way that David finally realized he’d spoken. He felt his face turn a dark crimson. Shit, he thought distantly, I haven’t done that since fifth grade.

Elizabeth rolled her eyes at him. “Grow up,” she said. “After your daddy finishes paying your way through state school, I mean.”

“Ah, snap!” said a large white man to her left.

“My parents aren’t paying a penny,” David said. “And I think you’re better than that, actually. I think that was just reflex and you didn’t really mean to say something that bitchy, so I’m going to ignore it.”

“What did you call me?”

“Okay,” the professor said, raising both hands, palms out. “Okay, let’s, you know, let’s find—”

“The American Dream is not a myth,” David said. “Not for me. Not for a lot of people in this room, I’m guessing. If you work hard enough, you can still make your mark in the world.”

“And how will you do that?”

“I don’t know. There’s a million ways to get to where I want to be.”

“And what if you get hit by a car or . . . or slip in your bathtub and break your neck on the way down, or you get cancer? There’s a million more random things that can go wrong before you do.”

“Look at Stephen Hawking,” he said. “Guy’s in a wheelchair. Can only move one finger. And he’s changing everything we know about the universe. You don’t have to be limited by the things that could go wrong.”

“You’re going to Kent State,” she said. “Where did he go to school? You’re proving my point. It’s too hard to get there for people who start on our level. Don’t you get it? We’re not going to be celebrities, we’re not going to be president, we’re not going to change the course of history. We’re the workers. We’re the Morlocks. And our children will be their children’s workers. And there’s nothing we can do to change our future. But music like this makes us believe we can.”

David shook his head. He wasn’t blushing anymore, he knew. He felt strangely calm. “What happened to you?” he asked.

“What?”

“Was it a bad breakup? Did your parents just get divorced? What I mean is, who did this to you? Made you so sad?”

“That—that’s enough,” said the professor.

“Life,” she said.

“Well, if it’s just life, I don’t see that you have any reason to complain,” said David.

“You don’t know me.”

David opened his mouth to respond, but before he could, Elizabeth gathered up her books and walked out of the room. The class watched her go and then, in unison, turned toward David. He shrugged and sank into his seat.

He sat there for only another moment. And then, before he could think better of it, David scrambled out of his seat and ran after her. But she was gone. He searched the staircase on one side and peered in the women’s room on the other. It was crazy, anyway. What would he have said?

“Over here, numbnuts,” Elizabeth said. She was sitting at a desk in the dark in the empty classroom behind him.

He stepped inside and closed the door. “I didn’t mean to offend you,” he said. “Or maybe I did. I guess I did.”

She sighed. “It doesn’t matter. I don’t know you. You don’t know me. It’s fine. Whatever.”

“I do know you,” he said, not daring to step closer. “I know that whenever you sneeze, you sneeze exactly three times into the crook of your left elbow. I know you’re right-handed but write like a left- handed person, which tells me you must have had a mom or a dad who was left- handed and who loved you enough to teach you how to write before you went to kindergarten. I know that when you get nervous, like when we’re learning something new, you whistle some Blink-182 song real low. I know you bite your nails but not in class. I know you used to smoke, because sometimes you pull out your purse and open the side pocket where you used to keep them before you realize you’re doing that and then look around to see if anyone noticed. I know that necklace you wear has some special meaning because every so often your eyes get this glazed-over thing about them and you reach to the necklace, twisting it in your fingers to make it go away.”

Finally, David paused. He felt light-headed, but needed to say a little more. There was a real chance, he realized, that he would never have another opportunity to do so. He knew how crazy he sounded. Crazy enough for a restraining order, maybe.

“The American Dream is not a myth,” he said. “It offends me when you say that, because I’ve worked really hard just to get here. One day I’ll do something that matters. I’ll have a big goddamn house and people will know my name. Someday I’m going to have all that. And I don’t really know how to prove to you that’s possible unless you come with me.”

Elizabeth didn’t answer. It was impossible to read her. Her eyes were cold brown pebbles.

“I think you are just about the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen,” he said. “I am in love with you, even though we’ve never really even talked before. I’m in love with the way you are. Your bluntness. Your intelligence. Your fragility. You are . . . just . . . lovely.”

Elizabeth looked back at him for a full ten seconds before saying anything. Finally, she said, “You can go.”

Later that night there was a knock on David’s dorm room door and he knew who it was without looking. When he opened it, there she was, her red hair bristly from the humidity. A cream-colored angora blouse clung to her body like a thin mitten. She set her book bag on the floor outside his room.

“I hate you and everything you’re about,” she said.

“No, you don’t.”

She stepped into his room. He closed the door. Even before it latched, her hands were on his body. They made love. When they finished, she took off her blouse and they fucked. Still later, they made love again, to the blue light of a television screen.

Lying in the dark, her head on his chest, long after he thought she had gone to sleep and he had passed the point of coherent thoughts, Elizabeth whispered, “I had a twin, once. An identical twin.”

“Shhh,” he said and stroked her hair. “I love you,” he said.

“You shouldn’t,” she replied.

He awoke in the darkness and he was alone.

No note, no lipstick on his dorm room mirror, no sign at all that Elizabeth had even been there except for the faint lingering of her scent, soap and melon.

David found her name in the student directory, called her dorm at Prentice Hall, got no answer. The next day she did not come to class. He had a girl he knew from History of American Lit escort him to Elizabeth’s room, but if she was there, she didn’t come to the door. He left more messages on her answering machine.

Around nine o’clock, three nights after they slept together, the phone in his room rang. She was crying.

“What?” he asked calmly.

“David, I’m sorry,” she managed. “I’ve been so mean to you.”

“It’s fine.”

“I didn’t know who else to call. I need your help.”

“What’s wrong? Did something happen?”

“I . . . I ordered pizza from EuroGyro. They always send out Catherine for me. She was supposed to work tonight. But when I called in my order, they sent some guy. I couldn’t open the door. I just ignored him until he went away. I don’t have anything left in my room to eat. Can you come and get me? Take me somewhere?”

David didn’t question it. Didn’t want to. This was her mystery, after all.

He picked her up five minutes later. Her lovely red hair was disheveled and he could tell by the clutter of her room that she hadn’t been outside in days. He took her to EuroGyro, where he paid for her pizza—which they shared at the bar, over a pitcher of beer. Afterward, they went to Palcho’s, a one-room donut shop on Main Street, near the university. Elizabeth listened while David talked about his family and his attempts at writing something meaningful. Whenever he asked about her childhood, she deftly spun the conversation in a different direction. He let her.

“I never answer the door for men,” she said finally.

That night she stayed in his dorm room. And the next morning she was still there.

“No, no, no,” she said, flipping through his CD case. “David, this is just awful.”

“What?”

“Cranberries, Enya, They Might Be Giants. There’s nothing in here older than 1990. It’s like some horrible teen girl’s CD collection.”

He shrugged. They were on his bed and she was leaning back against his chest, his legs crossed over her pale thighs. He loved the weight of her against his body. When she was done, Elizabeth tossed the binder across the room and pulled away from him, slipping on a pair of Keds.

“I’ll be right back,” she said.

She returned twenty minutes later with a stack of CDs in her arms, held sturdy by her chin. She dumped them beside his radio, selected a disc, and turned the volume up louder than he’d ever pushed it. A gentle guitar riff; a tap-tapping of some percussion instrument—he pictured a man hitting a wooden spoon against his legs; a solid male voice, and the song broke into something more, a beat that filled his head with cool images and colors.

“What is it?”

“Led Zeppelin,” she said. “ ‘Ramble On.’ ”

He sat against the wall, his eyes trained on the space in the corner, while she selected more songs, rocking back on her legs and staring at him intently. “Free Bird.” “Roundabout.” “Sympathy for the Devil.” “Time.” “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” “Brass in Pocket.” “Bad Company.” “Limelight.” “Crazy on You.” “Voodoo Child.” “Take the Long Way Home.”

“Thank you,” he said. “Where have I been hiding all this time?”

Elizabeth’s life was divided into manageable and repeating segments, and any derivation from her charted schedule seemed to lock her away into herself for a bit.

Every morning she drank a single cup of hazelnut coffee, which was dispensed from her single-cup machine. Then she signed online and checked the same four sites in order: the Plain Dealer, the Beacon Journal, Hotmail, and Drudge. Each afternoon, after classes, she got lunch from the Prentice Hall cafeteria, and took it back to her room on a beige tray, except for Wednesdays, when she treated herself to a take-out meal from Chipotle, eating in her locked car while she read the new weekly In de pen dent. One Wednesday, they arrived at Chipotle to find that all the spots in the lot had been taken, and, instead of driving to another restaurant, she had taken them back to the dorm and slipped under the covers, without eating, complaining of a headache until he went away. At seven-thirty, five days a week, she stopped studying and turned on Jeopardy, but never said the answers out loud. For a snack, at ten o’clock, she ate cinnamon toast. She spent most of the weekends in the library. But on Saturday nights, she always disappeared.

For the first couple weeks, he didn’t ask. When Saturday night came around and she told him she had plans, again, he found something else to do. But he knew she must leave campus because when he would go out to the bars with friends later, her car was always gone from the lot. And then, one Saturday night, just as he was steeling himself for the customary brush-off, Elizabeth said, “David, how much cash do you have on you?”

“About forty dollars,” he said. “In the bank, I mean. Nothing on me.”

She smiled. “You can borrow some of mine,” she said, pulling him off the bed. She reached into her panties drawer and pulled out a folded wad of twenties and tens.

“Jesus,” he said.

“It’s my bankroll.”

“Your what?”

“Bankroll. It’s not . . . well, it’s not real money. You can’t think of it like that.”

“It looks like real money.”

She shook her head. “You only use it to get more money.”

Elizabeth drove them to the Walmart in Ravenna, and parked behind a long charter bus surrounded by last year’s sedans. “Red Hats,” she said, as if that explained anything. “I like to play the ponies. Have you ever been to a track?”

David shook his head.

“Dark, smoky places. Full of men. But if you know what you’re doing, the odds are in your favor if you play long enough. I needed a group to go with me, because I couldn’t ever go alone, but I don’t have anybody. So I found them.”

The Red Hats, it turned out, were a kind of sorority for retired women who wore red hats instead of fezzes. There were more than twenty on the bus and they waved at Elizabeth as she entered, and cooed at David as he followed her to a seat in the back.

The bus took them to Northfield Park, a wide concrete coliseum a half hour away. Elizabeth stayed in the center of the Red Hats, leading David by the hand as he watched prissy horses pulling little carts through tiny gates. Inside the restaurant, the air was thick with the smoke of cheap cigars and thin cigarettes. They took a section of tables by a window and ordered food and beer while Elizabeth read through sheets of what looked like random numbers to him.

Betting on harness racing, like all horse racing, like life, she explained, was something called pari- mutuel gambling. Unlike betting on football, the odds changed based on the number of people betting. She tried to walk David through the basics of handicapping—something about pacing and whether or not the horse had tripped in the last race—but it was too much for David to keep straight.

“Look at this one,” she said, pointing to the stats on a horse called Santa Vittoria’s Secret. It was at ten-to-one, but had placed in a quarter of its last dozen races. “It has good value.” Instead, he put ten on Fatty Lumpkin, a horse at three-to-one, because he’d recognized the name from the Lord of the Rings.

Four hours later, they got back in the bus with the Red Hats, David in a daze, his head heavy on his shoulders. He’d lost $240 of his girlfriend’s money. But she’d left happy, and $800 richer.

“Probability won out,” she said. “It usually does.”

She practiced the piano in a cramped room in the Music and Speech Building every Tuesday and Thursday. Sometimes he would arrive early to watch her through the square window, watch her lovely calm as she folded herself into some Poulenc or Chopin. That was when she was at rest enough to smile.

When they took a trip to Niagara Falls and she thought he’d gone out for booze, she had sung loudly in the hotel shower, sung with a girlish confidence that busted his heart. “Castle on a Cloud,” from Les Misérables. He’d taped her performance with his microcassette recorder.

He stole glimpses of her when they got ready for dates in her dorm room, as she looked in the mirror at herself and made her lips into a silent whistle as she brushed her hair.

Only he knew these moments. Let others have their low-rent women, he thought. Elizabeth was worth more because only he knew how to find her. And only she knew how to find him.

“Where’re we going, Dad?” asked Tanner.

David knelt in front of his son, tying the boy’s Converse high-tops before zipping his coat and ruffling his hair. “Out,” said David.

“But where?”

“On a little adventure.” He took his son’s hand and led him through the kitchen to the garage, where the restored canary-yellow Volkswagen was parked.

“Ugh!” said Tanner, trying to pull his hand away from David. “Is this like the museum trip where you wanted me to see Mayonnaise on the wall?”

“Manet,” corrected David with a smile. “No, buddy. We’ll suspend your art lessons until you’re five.”

“What does suspend mean?”

“It means ‘delay’ or ‘wait until later.’ ” David opened the door and pushed the seat up for Tanner, who climbed into the booster seat in the back and buckled himself in.

“When do I get to sit up front?”

“When you’re a little taller,” David said. At the last visit to the pediatrician’s, the doctor had said the boy was in the twenty-fifth percentile as far as height, small for his age. It had been weirdly alarming and David had stayed up well into the night wondering if he’d somehow neglected the boy’s nutrition or stunted his growth by letting the boy sip his Coke whenever David had one with dinner.

The car’s ignition fired with a noise that sounded like the coughing of a fat smoker after a flight of stairs. He didn’t like taking her out of Akron, but he’d just had the Bug tuned and figured she could get them to Mansfield and back in one piece. In a moment they were bounding down Merriman, feeling each chuckhole and patched bit of pavement along the way. David stole a quick glance at the house on Primrose Lane as they passed—there was no sign of life there. The yard of Kentucky bluegrass was overgrown. Then again, so was his. He guessed it must still be empty—which would make it the only vacant property this side of town. There was no For Sale sign out front, though.

“But where are we going?”

“We’re going to hear your mother sing.”

After his book began to climb the charts, but before Tanner came along, David had been introduced to a lawyer in Mansfield, a gruff man of giant proportions who wore candy-cane suspenders and woolen slacks. Man’s name was Louis Bashien, and he was a bit of a savant when it came to probate matters and financial planning. He was the first one who told David to sock away some cash and identification. He was the first one to tell David to buy a gun.

“Trouble comes to money like flies to shit,” he’d told David four years ago. “Be a good Boy Scout. Be prepared.”

And so David had given Bashien his money, to hide it, twist it, make it grow. He’d gotten a license and bought a gun. And he’d purchased a safe-deposit box at the bank across the street from Bashien’s office in downtown Mansfield, an hour south of Akron. Elizabeth liked the idea of a little insurance against the future and so she went down with him when he filled the box. Inside went ten thousand in cash and their passports. He remembered how she’d spotted the neon sign to the robotics museum on the way home and how the sight of it had caused her to retreat into herself and grow silent, the way she used to in college.

When he asked her, later, what had upset her, Elizabeth’s response had been as mildly amusing and maddeningly vague as the rest of her. “The robot in the window, on that poster in the window. Whoever made it is dead now and it has to live forever in that shitty museum, alone. It’s sad.”

After she died, he’d gone back to Mansfield, once. That time he had deposited his handgun, a handsome nine-millimeter revolver, the kind cops used to carry, and the microcassette player with her Les Mis performance tucked inside. It had not seemed like a hot idea to keep either one in the house with him.

He had forgotten the tape until today, until Paul had come inside his house, trailing memories. Now all he wanted in life was to hear her voice again and to share that with their son.

Tanner followed him inside the one-floor muni bank an hour later, skipping a few steps behind, tugging at the back of his jacket. They were escorted to a cozy alcove and after a minute a short woman brought out a long box and set it on the table in front of them. David waited until she walked away before he opened it.

“Whoa!” said Tanner, whistling approval and awe at the money stacked inside in bundles of twenty-dollar bills. Behind the money, the gun was still wrapped in a blue washcloth. He could smell its grease, an angry, paranoid stench. Resting on top of the money was the little recorder. He picked it up and handed it to Tanner. Then he locked the box and nodded at the woman, who came to reclaim it without a word.

They sat in the parking lot and listened to it five times. Nobody cried. In fact, Tanner was bouncing on the back seat in an excitable rush. “I love her voice!” he said. “I love the way she sings!”

Finally, David buckled his son back into his seat and pulled out of the parking lot, heading back through town. Tanner saw the sign’s neon glow first, a dull pinkness against the buildingscape, which was falling into shade before the setting sun.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“A robot lives there.”

Tanner blew a loud raspberry. “Nuh- uh, Dad!”

“It’s true. His name’s Elektro.”

“Is it a dangerous robot? Like General Grievous?”

“No. He’s a friendly robot.”

“Like WALL-E.”

“Like WALL-E,” David agreed. “But taller.”

The Mansfield Museum of Circuitry and Robotics was located in an old bank downtown, past the abandoned and rusting buildings where Westinghouse had once produced affordable and durable appliances for consumers across the Midwest. The factory had employed half the town. When the late-seventies manufacturing bubble burst, it destroyed the local economy. Westing house’s laboratories and office space were emptied and local businesses that fed off its employees—bars, convenience stores, retail—perished. That’s one reason why a seldom- visited robotics museum could afford to rent a historic gothic bank, David supposed.

David had come across an article in the Plain Dealer years ago about the museum’s curator and his efforts to restore Elektro and to rebuild Sparko, its trusty servant, a robot dog that had been run over by a car. According to the writer, Sparko’s eyes had been photosensitive. If you waved a flashlight on the ground, it would follow the spot of light anywhere. Unfortunately, some engineer had left the door to the lab open one night and Sparko had been attracted to the headlights passing by outside. The idea that there was this odd man restoring a robot friendship here in Mansfield, where the biggest employer was a toilet factory, had always stuck with David like a burr on his sleeve, more so since his memories of Elizabeth were entangled with the place, too. What was it that had made her so sad about the notion of an eternal life?

David pulled into a diagonal space directly in front of the museum. Theirs was the only car downtown. Most of the nearby storefront windows had been newspapered or painted over long ago. Across the street, a homeless man warmed himself on a sewer grate. Above the door the neon sign pulsed rhythmically: Meet Elektro the Robot.

“Cool,” said Tanner, unbuckling his car seat.

David helped the boy out of the car and took his hand, keeping a close watch on the bum across the street. But the bum didn’t move.

Beyond the front doors, the air was brutally warm. Somewhere a heater shuddered against a wall, blowing dry air into the museum with its last ounce of strength. They stood there, David and the boy, for a few moments, looking about the lobby. Dozens of black-and- white framed photographs of the 1939 World’s Fair hung on the scarlet walls. In each, a seven- foot-tall smooth humanoid robot performed some new trick. Here he was smoking a cigarette. There he was tossing a hot dog to Sparko as the dog sat on its hind legs, its mouth wide open. And here was one where Elektro was shaking hands with a man dressed as the Tin Woodsman from The Wizard of Oz. The Tin Woodsman might have been crying in agony.

After a while, David led Tanner to the ticket counter, behind which a doorway to some office or storage room was blocked by a black velvet curtain where dust bunnies clung, their tails dancing in the breeze of the dying heater. A brass bell rested on the counter next to a laminated hand-drawn sign: Ring For Service.

David rang the bell. Its sound reverberated in the shallow room.

From behind the curtain came the sound of metal things falling to the floor, as if the bell had set off some booby trap that had caused a box of tools to tumble from its perch.

“Is it the robot?” Tanner whispered, clutching his father’s hand.

“No,” David said. “It’s the tour guide.”

A little man trundled through a seam in the curtain. He stood just over five feet tall and had a wiry white beard that hung below his chin in a braid. The man was small, but not a midget. Old, but not ancient. A smell followed him out of the back room. Cinnamon? David watched as the man climbed onto a stepstool to better see his visitors from behind the counter. He noticed the man had something in his right hand. Something squarish and white. A cell phone?

“We’d like to see Elektro,” David said.

The man brought the white object up under his braided beard. In a flash, David knew what it was. He had only enough time to realize this was about to be one of those moments Tanner would likely recall in therapy one day. There just wasn’t enough time to explain before it happened.

The man behind the counter was the curator, of course. And the thing in his right hand was not a cell phone, but an electrolarynx he had used to talk since doctors at the Cleveland Clinic had removed a fivepound tumor—and his voice box—from his throat, in 2004. Because he was old and his hearing was going, he kept the box turned up to eleven, so he could hear what he was saying, too. What came out when he finally addressed his first guests in three weeks was both manufactured and loud. “JUST YOU AND THE BOY?”

Tanner had not let his father carry him for more than a year, but by the time the curator had said “JUST YOU . . .” the boy had scrambled up David’s legs and had buried his eyes in the fold of David’s right elbow.

David gave the curator a one-moment sign. The man nodded back. Obviously, he was fairly used to this sort of reaction from young ones.

Walking back toward the door, David slowly pried his son off him and set Tanner down. The boy peeked around him, spotted the curator, ducked his head back behind his dad, and let out a small moan. David felt pangs of guilt but knew it was important that he not just pack the kid up and turn tail for home. That would only compound the terror and the nightmares. He realized this was the first time he was going to ask his son to face a fear. Was Tanner old enough for such a lesson, at four?

“Tanner. Tanner, listen to me,” David said.

“You said it wasn’t a robot. He looks so real.”

“Tanner, that man is not a robot.”

Still shaking, the boy gave David a look of reproach. That was new, too. And David felt it deeply. This was the first time he had told his son the truth and his son had decided that he was lying. Not just teasing. Lying.

“Sometimes people get hurt, their throat gets hurt in an accident or something,” he said. “And sometimes, when they’re fixed up, they can’t talk like you and me. They have to use a little voice box, which they hold up to their neck. The box lets them sort of talk but it sounds really weird when they do.”

Tanner stopped shaking a little bit. He stole another glance at the curator, who waved at him.

“How come I never saw anyone like that before?” he asked.

“Probably because we don’t get out enough, kiddo,” David replied. “My fault.”

And then Tanner smiled and all was well with the world once more. “Can I have one?” he asked, already envisioning a scenario, no doubt, that included a sudden leap from the shoe closet with an electrolarynx pressed to his neck as Aunt Peggy searched for the duster.

“LUKE, I AM YOUR FATHER,” the curator said in his mechanized voice.

Tanner laughed, but squeezed his dad’s hand as he did. “Cooooool!”

David nodded a thank-you to the curator. “Just us,” he said, handing the man a ten-dollar bill.

The curator shoved the money down the front pocket of his oil-stained overalls. He stepped off the stool and swung a section of the counter up so he could walk out from behind it, even though he could just as easily have ducked. “FOLLOW ME,” he said as he stepped toward a steel door that had once led to the bank’s gigantic vault, but which now held more priceless treasures. From his front pocket he withdrew a six-inch-long skeleton key, which he considered for a moment before handing it to Tanner.

The boy’s eyes grew ever wider as he felt the weight of the key in his palm. David sensed that his son believed this to be a magical key, one that might open doors that led to other worlds. It certainly looked like a key from some fairy tale. Even David caught himself imagining the door opening onto a forestscape bathed in gold and green light from a star not unlike our own.

Tanner let go of his father’s hand and walked deliberately to the metal door. The boy slipped the key in the hole below the glass doorknob and turned it lightly. What followed was a loud tumbling of gears from inside that seemed to go on for ten seconds. Finally, it ended with a grinding THUNK! and the door creaked open an inch.

“IT’S A GOOD THING YOU CAME,” the curator said. “THAT DOOR ONLY OPENS FOR CHILDREN AND I LEFT MY HAT BEHIND THE LAST TIME I WAS INSIDE.”

Tanner smiled and handed the key back to the curator, watching it disappear in that front pocket again, an adultlike expression of loss in his eyes. He was old enough, then, to understand that magical moments were rare and fleeting.

The museum was dedicated to the history of man’s attempt to create a machine in his own image. A pathway snaked across the main room, past photographs and displays of early Westing house models, machines that vacuumed or served canapés, some with misguided names like Mammy Washington.

“Is Elektro here?” Tanner asked his father.

“RIGHT THIS WAY, YOUNG MAN, RIGHT THIS WAY,” announced the curator, with a flourish of his hands that would make a carnival barker blush. “NO SENSE DELAYING THE MAIN ATTRACTION.”

They soon arrived at the back of the museum, where a floor-to-ceiling black velvet curtain hung from the rafters.

“BEHOLD, THE APEX OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING. THE REALIZATION OF MAN’S IMAGINATION. THE WORLD’S MOST FULLY FUNCTIONAL ARTIFICIAL HUMAN. EEEEEEELEKTRO.”

Pocketing his electrolarynx, he pulled at a long length of rope nearby and the curtain parted.

Slowly, slowly, a stainless steel frame was uncovered. It was easily more humanoid than the robots that had preceded it, and yet, less human. Elektro was seven feet tall, a barrel-chested giant with cool gray eyes and a mouth that suggested it was either attempting to smile or was gritting its teeth. It was frozen in time, its arms and hands extended outward in a gesture reminiscent of a model from The Price Is Right showcasing a new blender. There was a peculiar smell emanating from the robot; it smelled of waterfall mist, of positive ions, of ozone.

“Wow!” shouted Tanner, hopping in place excitedly.

David nodded. “Pretty cool,” he agreed. “Can it still blow bubbles?”

The curator dropped the rope and returned the white box to its place under his wizard beard. “I’VE NEVER ACTUALLY GOTTEN UP THE NERVE TO PLUG IT IN,” he said. “I’M AFRAID IF I DO, IT’LL FRY ITS INSIDES AND BURN THE PLACE DOWN.”

Tanner looked distractedly down at the thick and tattered electrical cord trailing behind Elektro’s left leg and at the wall socket a few inches away. David took a moment to get a better grip on his son’s hand, before he got any sudden Frankensteinian ideas.

“AFTER THE 1939 WORLD’S FAIR, ELEKTRO TOURED THE COUNTRY AND MADE A DECENT LIVING FOR MANY YEARS. THE MONEY WESTINGHOUSE TOOK IN FROM HIS ENGAGEMENTS WAS SET ASIDE IN A SPECIAL FUND THAT COULD ONLY BE USED FOR HIS UPKEEP AND MAINTENANCE. THE INTEREST FROM THAT FUND IS WHAT KEEPS THIS MUSEUM OPEN TODAY.”

“He had a dog, you know,” David told Tanner. “He had a pet robot dog.”

“Really?” The boy turned to the curator. “Is the robot dog here, too?”

“AFRAID NOT.”

“The scientist made the dog so that it was attracted to light, so that whenever it saw a beam of light, it knew to follow it,” said David. “Do you understand?”

Tanner nodded.

“But one day the scientist forgot to shut the door, and during the night the dog ran out into the street and it got hit by a car.”

Tanner looked at the curator again. “Is that true?” he asked.

“NOT A WORD OF IT,” the curator said, looking annoyed.

“Isn’t that the story you told the reporter a couple years ago?” asked David. “I thought that’s the story I remembered.”

“SURE. THAT’S WHAT WAS WRITTEN. BUT THAT’S NOT WHAT HAPPENED.”

“What’s the real story?” asked David.

The curator looked up at Elektro, as if consulting with him before he continued. And when he did speak again, he did so nervously.

“THE TRUE STORY IS . . . STRANGER,” he said. “WHAT REALLY HAPPENED WAS THIS. ONE NIGHT, THE ENGINEER, WHOSE NAME WAS SAMUEL MCGEE, HE LEAVES THE LAB. GETS INTO HIS CAR. STARTS TO DRIVE HOME. SPARKO RUNS OUT INTO THE STREET. SAM RUNS IT OVER. DOG GETS STUCK IN WHEEL WELL, SENDING THE CAR INTO A TELEPHONE POLE. THE CRASH KILLED SAM. KILLED WESTINGHOUSE’S ROBOTICS DEPARTMENT, TOO.”

“The dog caused a crash that killed the man who invented it?”

“WAS IT REALLY SPARKO?” The curator shrugged. “SOMETHING ELSE THE WRITER GOT WRONG: SPARKO’S EYES WERE NOT PHOTOSENSITIVE. THE DOG WAS MADE TO RESPOND TO VOICE COMMANDS. BUT IT WOULD ONLY RESPOND TO ELEKTRO’S OWN VOICE.”

“But how did Sparko get out?” asked Tanner.

“THERE’S THE REAL MYSTERY. THE JANITOR SAID HE LOCKED UP THAT NIGHT. IF HE’S TELLING THE TRUTH, THERE’S ONLY ONE THING THAT COULD HAVE LET THE DOG OUT.” He glanced, coldly, to Elektro. To David, the robot suddenly seemed to be listening to them and pretending not to be alive. “ELEKTRO MUST HAVE PLAYED A PART IN IT. AFTER ALL, THE DOG COULD ONLY HAVE RUN INTO THE STREET IF ELEKTRO HAD CALLED TO HIM.” And with that the curator continued walking down the length of the museum to the models of later robots built by other dead Westinghouse engineers.

“Dad,” whispered Tanner.

“What, bud?”

“Dad, that was the best story!”

On the way home, they counted the stars. David had once heard—though he had no idea if it was true—that there were exactly eighty-eight constellations in the summer sky. “Can you name that one?”

“The Big Dipper!” shouted Tanner. “Duh. Who put the stars in the sky, Dad?”

David felt his blood chill. That had been his line, once. One of his first memories, actually: Riding in the car—in the front seat, beltless, natch—with his mother, when he couldn’t have been more than two, two and a half, watching the factories of Cleveland belch fire as she drove them from Lakewood to his babysitter’s in Bedford before work. As soon as they were away from the fire, the stars would appear. It had been five in the morning then, and not night. He’d asked that same question, every single day. To David, this was a bad omen. His worst fear, unsaid, was that his boy would grow up to be just like him.

Still, he used his own mother’s old answer. “God,” he said, though he no longer believed it to be true.

“Why?” asked Tanner.

“Some people think it’s so that we can see how beautiful they are.”

“Oh. They are pretty stars. I like them.” For a couple minutes there was silence. David was about to flick on the radio when his son spoke again. “Why do you think God put the stars in the sky?”

A stumper. No way to answer that one, for now. And the kid was only four. “So the Indians could read at night before electricity was invented, I think,” he said at last.

Soon Tanner was asleep. As he snored into his shoulder in the back seat, David called Paul on his cell phone. He picked up on the first ring. “I’m in,” said David.

Copyright © 2012 by James Renner

James Renner is a reformed muckraker who now writes novels and short fiction. He also occasionally dabbles in film and comedy. his debut novel, The Man from Primrose Lane, will be published this month by Sarah Crichton Books.

Reward yourself with our appealing Bath towel Sets in Pakistan. Our Hand Towel in Pakistan are manufactured to the highest standard from start to finish. Shop Online!

AUA is one of the best Caribbean Medical University to study medicine with its accredited programs.