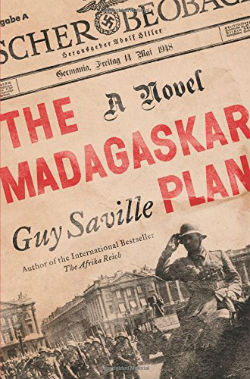

The Madagaskar Plan by Guy Saville imagines an alternate history where a Nazi victory in World War II brings thier “final solution” even closer (available July 28, 2015).

The Madagaskar Plan by Guy Saville imagines an alternate history where a Nazi victory in World War II brings thier “final solution” even closer (available July 28, 2015).

The year is 1953. There is peace in Europe, but a victorious Germany consolidates power in Africa. The lynchpin to its final solution is Madagaskar. Hitler has ordered the resettlement of European Jews to the remote island.

British forces conspire to incite colony-wide revolt, resting their hopes on the expertise of Reuben Salois, an escaped leader of Jewish resistance.

Ex-mercenary Burton Cole scours the island for his wife and child. But as chaos descends and the Nazis brutally suppress the nascent insurrection, Cole must decide whether he is master of-or at the mercy of-history.

Chapter One

Schädelplatz, Deutsch Kongo

26 January 1953, 06:30

Panzer crews called it Nashornstahl: rhino steel. It was supposed to be impregnable. A girder of it had been welded across the entrance.

There was a crackling boom, like thunder heard from within a storm cloud, and the door exploded. Shards of metal and flame flew down the corridor. Before the smoke cleared, Belgian guerrillas poured through the barricade, kicking aside the mangled girder. Among the Europeans were black faces.

Oberstgruppenführer Walter Hochburg felt a shudder of incredulity. Then the fury swelled in him, his black eyes glittering.

No nigger, no breathing nigger, had ever set foot in the Schädelplatz, his secret headquarters. He raised his rifle above the sandbags—it was a BK44, the one Himmler had awarded him—and lashed the trigger. Waffen-SS troops fired alongside him.

More guerrillas surged into the passageway.

“Stand your ground,” roared Hochburg. His voice was a raw baritone.

To either side of him, men were retreating to the next redoubt. Hochburg followed with a slack stride, certain of his invincibility, his rifle searching out dark skin. He reached the second wall of sandbags and dipped behind them to reload.

“Oberstgruppenführer!”

Before him was his new deputy, Gruppenführer Zelman: flat-faced, blond, unblinking. The buttons on his uniform were as untarnished as virgin silver. He had emerged from a side passage.

“What news?” asked Hochburg.

Zelman huddled low. “A thousand guerrillas, maybe more, including artillery. The main entrance and southern walls have been breached. We can’t hold out much longer.”

“Where are my helicopters?”

“You must leave, Oberstgruppenführer. Immediately. Your bodyguards are waiting to escort you to Stanleystadt.” Stanleystadt: Kongo’s great northern city.

“And have the blacks in our sanctum? Never.” There shouldn’t be a single negroid within a thousand kilometers of the Schädelplatz. Hochburg slammed a fresh magazine into his BK44. “Get a rifle in your hand and fight. You, the auxiliary staff, kitchen porters, every last man.”

“I didn’t come to Africa to die, Oberstgruppenführer.”

“Then you have no right to be here.”

Not for the first time Hochburg regretted dismissing Kepplar, his former deputy. Whatever his failings, there was a man who would have relished defending the Schädelplatz. Zelman was a cousin of Reinhard Heydrich’s wife and had been assigned to him after the invasion of Rhodesia faltered. To keep an eye on me, Hochburg told him the day he arrived.

A grenade landed between them.

Zelman grabbed Hochburg and yanked him into the side passage. The blast turned the entrance into a cascade of bricks.

“I would have thrown it back,” said Hochburg as he got to his feet, swiping away the dust. When the attack woke him, he had put on his black dress uniform, the material straining against the brawn of his shoulders; now it was floured and torn.

Zelman led the way through the stone corridors of the Schädelplatz, till they turned into the main thoroughfare. Hochburg stopped abruptly.

He had been here fifteen minutes earlier, demanding the base at Kondolele get his gunships airborne. There should have been sentries by the door; instead, only the smell of the wind. He pushed his deputy to one side and stepped into the command center. The cloud-riddled dawn shone down on him, wands of orange and coral-pink light.

Hochburg felt a shifting inside himself. “It can’t be…” he said. It sounded like his jackboots were treading on snails.

The command center had taken a direct hit. In the middle of the room, the table map of central Africa was broken in two; above it, jigsaw pieces of sky. The black triangles that represented units of the Waffen-SS lay scattered on the floor. Hochburg stooped to pick one up, rolled it in his fingers as if it were a divining stone. Bodies were strewn on the floor, cables sparked. Only the telex machines seemed unaffected: they continued the merry chatter of war. By now he should have been the master of Northern Rhodesia, its copper mines serving the Reich, its cities and dusty plateaus cleansed of the negroid threat. His panzers had invaded the previous year and found British forces waiting for them. The swift victory he’d promised became a protracted retreat, the British eventually crossing the border and encircling Elisabethstadt, Kongo’s third city. A pendulum siege of attack and counterattack had lasted ever since. With Hochburg’s army engaged in the south, the remnants of the Belgian Force Publique took advantage of the situation and launched a full-scale guerrilla war in the north. The Belgians, the previous rulers of Kongo, had been fighting an insurgency since the swastika was raised over the colony a decade earlier; now they were emboldened.

A female radio operator was beseeching her mouthpiece. Hochburg buried the black triangle in his pocket and placed his hand on her shoulder. Her hair was thick with dust, the right side of her face burned. “Any word on the helicopters, Fräulein?”

“We lost the line to Kondolele, Oberstgruppenführer.”

“Reinforcements?”

“Stanleystadt reports that a new offensive started against the city an hour before dawn. They can’t spare any manpower.”

“You must leave,” said Zelman.

Hochburg scraped his palm over his bald scalp. “No.”

“With respect, Oberstgruppenführer, if you’re captured, they’ll parade you in the streets of Lusaka—”

“You think I care?”

“Germania* might, especially when you stand before a Negro court.”

Hochburg sighed. “You would be more convincing, Zelman, if you weren’t so desperate to save yourself.”

“You can’t command a counteroffensive from here. Stanleystadt is your better hope.”

“This place is my home.”

“There are no helicopters, not enough men. It’s already lost.”

The radio operator put up her hand to speak. “The Schädelplatz is more than the walls around us. It is an ideal. A beacon for our hearts.” She was too shy to look at Hochburg. “As long as you survive, Oberstgruppenführer, so will it.”

“The girl’s right,” said Zelman. “We don’t have to die.”

Hochburg considered her words, unwilling to admit the truth. He patted her gently. “There’s nothing more you can do. Come with us—you’ll be safer.”

“I shall stay, Herr Oberstgruppenführer. I’ll keep trying to reach the helicopters.”

“You see, Zelman. Give me a battalion of girls and this war would already be won.”

He stormed from the room, his rifle held ready.

“Where are you going?” Zelman called after him.

Back in the passageways, the lights flickered above Hochburg. There were sporadic snorts of gunfire, and the shouts of Belgian guerrillas echoed along the walls. He was disappointed not to cross any as he made his way to his study.

The Leibwachen—his personal bodyguard—was waiting outside. He had dismissed them earlier as, goaded by Zelman, they fretted over his every move. All were dressed in dark combat fatigues with BK44 assault rifles. One held Fenris—his Rhodesian ridgeback—on a leash. Hochburg cupped the dog’s face in his hands, inhaled his gamey breath.

The French windows of the study had been blown inward, showering the floor with glass. A spectral smoke clung to the air. “Bring me some gasoline,” said Hochburg, casting his eyes over the walls of books. “Then get down into the square and secure the area. Somebody carry the dog.”

He flopped down at his desk, unlocked a drawer, and took out a piece of tightly bound sacking. Inside was a knife. There was a blink of silver as he withdrew it. This was the blade Burton had wanted to drive into his heart.

Burton Cole.

He was to blame for the death of Hochburg’s great love: Eleanor. Burton’s mother. She had chosen her son over him and, in doing so, condemned herself to a savage death. Hochburg would never forgive Burton. All these years on, his grief for Eleanor remained as raw as his need for retribution. His desire to watch her son burn—literally burn; to luxuriate in each crackling scream—quickened his blood more than ever. It was the itch of a phantom limb, beyond relief. Burton was dead: torpedoed and drowned off the coast of West Africa. Hochburg had issued the order himself. It was a decision he had come to lament.

As the war in Rhodesia had spread back across the border to Kongo, he spent his nights imagining Burton’s final seconds. The boy’s panic as the ship began to list and fill with flames; the dilemma of surrendering himself to the fire or waves. A man would always throw himself overboard: the virulence of the human organism demanded that it preserve itself, if only for a few minutes longer. Inevitably, Burton would breathe salt water: that was the moment Hochburg regretted.

He had been cheated of his final look into the boy’s eyes, its exchange of triumph and failure. Then Burton would descend into the darkness and oblivion, a release Hochburg had been denied. He knew who suffered the most: Hochburg lived with the pain of losing Eleanor every day.

A Leibwache entered carrying a canister that sloshed with fuel. Behind him, Zelman stumbled into the room. “They’ve reached the command center. We’ve only minutes to spare.”

“What happened to the radio operator?” asked Hochburg.

His deputy went to the portrait of the Führer and flicked the switch hidden in the frame, doing so with a familiarity that made Hochburg bristle. The painting swung open to reveal a secret chamber. In the ground was a trapdoor that led to an underground passage out of the Schädelplatz.

“I’m not slinking out of here,” said Hochburg, sheathing the knife.

“Oberstgruppenführer,” implored Zelman. “We must go now.” His voice was sucked into the passage.

Hochburg turned to the Leibwache with the petrol. “The books,” he said. It may have been too late to save the Schädelplatz, but his enemies would not make spoils of his precious volumes. He supervised the dousing of his library, then ordered Zelman to burn them; striking the match himself would be too heartbreaking.

He stepped to the veranda. Below, the square was empty except for his men creating a perimeter. Streaks of light blazed on the hallowed ground as the bombardment continued overhead. There was one final object he had to save.

The most prized thing of all.

* * *

Beneath his boots was an expanse of human crania. Twenty thousand nigger skulls, as Hochburg thrilled to tell visitors. This was the place that gave the Schädelplatz its name: the “square of skulls,” the ground cobbled with bone.

In the rosy dawn mist, he allowed himself to savor the square one final time. It was the fortress of his heart: a vast quadrangle, the perimeter covered by cloisters, with guard towers on each of the corners, from which soldiers were firing into the jungle beyond. The northern wall was obscured in scaffolding where they were repairing the damage wrought by Burton and his team of assassins the year before. Burton had been hired by a cabal of Rhodesian industrialists and British intelligence; when Burton failed, Hochburg used this attempt on his life to justify his attack on Rhodesia. Flanked by the Leibwachen, Hochburg ransacked the workmen’s equipment for a tool, then strode into the center of the square. Fenris bounded after him.

Hochburg raised the pickaxe above his head and brought it crashing down—once, twice—spitting mortar and chips of skull.

One of the guard towers vanished in a balloon of fire. There was a second blast and a section of the wall was punched wide open. A tank rumbled into the square; behind it came Belgian fighters, one of them carrying a banner of yellow stars against a peacock-blue background: the old flag of Belgian Congo and now a symbol of resistance. They wavered as they saw the ground.

“Where does a guerrilla army get a tank?” said Hochburg. It was an old British Crusader from the desert war against Rommel.

He redoubled his work, swinging the pickaxe with a fury, vigilant of the skull at the dead center of the square. The tank swiveled in his direction, fired, the shot reducing his study to a smoking wound. More SS troops emerged onto the square.

Zelman appeared at his side, clutching a Luger that reeked of packing grease. “Oberstgruppenführer, there’s no time for this.”

Hochburg shoved him away. The Leibwachen were a corona of gunfire around them. The pickaxe struck the ground again—and the skull at the center was free.

Fenris edged forward and sniffed as Hochburg carefully picked it up. He brushed flakes of cement from it, never believing that it had been disturbed, and stared into the hollows of its eyes. After Eleanor had chosen Burton over Hochburg, she’d fled into the jungle and been murdered by savages. Hochburg had hunted them down. The skull in his hand belonged to the first black he’d killed, a deed that saw the beginning of his mission to transform Africa. He had laid the square in Eleanor’s memory.

His dreams, his ambitions for the continent weren’t supposed to end like this.

Hochburg wrapped the skull in the sack he had taken from his study. He would defeat these insurgents: drive them into the jungle till the trees dripped scarlet. Then raise a new Schädelplatz, grander, more awe-inspiring than anything before.

The square was being overrun by Belgians.

“My garden,” said Hochburg. “That can be our escape.” He made a chivalrous gesture to his deputy. “Show us the way, Gruppenführer.”

Zelman remained within the huddle of Leibwachen, unblinking.

Hochburg ran from the center of the square, Fenris at his heels, the Leibwachen struggling to keep pace. They reached the cloisters as another tank broke through the far wall. It trundled toward them, shielding more guerrillas, the Belgians concentrating their fire on the small band of Nazis beneath the colonnade. Hochburg’s Leibwachen were falling around him. He fired his BK44.

“Save a bullet for yourself,” said Zelman. “You mustn’t be taken alive.”

Hochburg ignored him: his final rounds would be for blacks. He grabbed Fenris by the leash and raced toward the garden gate. Close behind he heard the slap of Zelman’s boots.

The second Crusader was armed with a flamethrower. A jet of orange and ebony roared through the quadrangle. Skulls that had been gathered from all six provinces of German Africa were reduced to cinder.

Shielded by the cloisters, his lungs charred, Hochburg reached the archway that led to the garden. It was his sanctuary. He tended it personally: dug the soil till his back ached, propagated every plant with his own fingers, the way Eleanor had taught him.

Now it writhed in flame.

He barely registered the intensity of the heat. Fenris broke free of the lead and galloped through the foliage to where cultivated land and jungle merged. For a long moment Hochburg stood motionless, his jaw listing and feeble; then he chased after the dog, into the inferno.

Chapter Two

Suffolk, England

28 January, 15:30

“STOP THE CAR.”

“We’re not there yet.”

“Just stop!”

The taxi driver braked sharply.

“Now back up. I saw something.”

The driver went to reply, then thought better of it. He put the car in gear and reversed down the empty lane. On either side was a wall of dank woodland: oak, ash, elm. Fading sunlight cut through the bare canopy.

“Here.”

The car came to a halt again.

Burton Cole climbed out and stared at the gap in the trees. He felt a tightening in his throat. Above him, branches creaked in the wind. He never should have sent the telegrams.

“It’s well hidden,” said the driver, following his gaze. “Yours?”

Burton shook his head. He had wheat-blond hair and eyes the color of an autumn afternoon, calm but alert, hard as a rifle butt. Concealed among the trunks was a black Riley RME. He put his hand—his right hand, his only hand—into his pocket and pulled out a banknote. “You can drop me here,” he said, offering it through the window.

“No way I got change for five bob.”

“Take the rest of the day off, buy yourself a drink. And if anyone asks, you never came out here. Or saw me.”

“Is it the law?” The driver looked uncertainly at the money.

“Jealous husband,” answered Burton with a forced wryness.

The driver gave an understanding nod and crumpled the note in his hand. “Couple of pints and I can’t remember a thing.”

Burton lifted out his haversack and shut the door. He was unshaven, wearing a sheepskin jerkin under a secondhand suit. The trousers and jacket were cut from scratchy brown rayon; sweat from a stranger’s body lingered in the cloth. When Hitler had returned the Dunkirk POWs to Britain, rather than sending them in uniform, he’d ordered a quarter of a million of these “dove suits” hastily made. Few of the homecoming prisoners wanted their new clothes. They were to be found heaped up in rag-and-bone stalls, promised to clothe generations of vagrants.

The taxi made a three-point turn and accelerated away in the direction of the railway station where Burton had arrived earlier that afternoon.

Moments later—silence.

As soon as he was alone, Burton reached into his haversack. He took out his Browning HP pistol, inserted a clip, then secured it in his waistband. He was less than a mile from home, and knew this spot well. Before he bought the farm he’d parked here with Madeleine on several occasions. It was a discreet place to leave the car while they vanished into the trees to feel a bed of leaves beneath them. Perhaps the Riley belonged to a couple looking for some privacy.

He crossed over to it and touched the bonnet: the metal was cold. Peering through the window, he found nothing except an ashtray overflowing with cigarette butts. All the doors were locked.

Burton tugged the collar of his jacket around his neck; his breath smoked the air. This was no weather for lovers.

The mud revealed footprints—two pairs, men’s—that had left the car and joined the road heading toward the farmhouse. Burton followed them, his pace soon quickening, boots drumming a lonely sound. They were the ones he’d acquired in Angola, taken from the feet of a dead man, the laces badly tied. He’d never imagined how difficult it would be to do one-handed.

He had been a fool to send the telegrams.

The first was from Cape Town, before he was admitted to the hospital, when he was delirious with exhaustion and self-recrimination. The message had been dispatched to Madeleine’s house in London, all caution abandoned. Her husband had sent Burton to his death in Kongo—what might he have reaped back in England? YOU ARE IN DANGER, it read. LEAVE IMMEDIATELY! ON MY WAY BACK TO YOU. Even in his fevered state he changed the last words before they were tapped in: ON MY WAY HOME. He sent another from Mombasa and then one more from Alexandria, on Christmas Eve, the words identical, each message increasingly desperate. It was probably too late, but he couldn’t bear any more days of unresting seas creeping by while he was impotent to help; he didn’t dare to think what might have happened. There were no replies.

Woodland gave way to open fields. Ten minutes later, Burton was staring at a weather-beaten sign: Saltmeade Farm. This moment had sustained him on his long journey. He’d clung to the image of the windows burning bright, the smell of applewood curling from the chimney, Maddie opening the door in her cornflower-blue dress, her belly swollen with the baby she would soon have. Their first child. He would clasp her and sink to his knees, beg forgiveness for leaving her to kill Hochburg in order that he could forgive himself.

The sign brought neither relief nor welcome, only anxiety and the anger that had throbbed inside him since he’d left Africa.

Five hundred yards of potholed driveway led to the farm; from here the house wasn’t visible. He hurried on, assuming it must be a trap, but the murmurings of hope were too strong. That’s why he’d come to the farm first.

“Please, God,” whispered Burton to the empty heavens. “Please.”

He hadn’t prayed since he was a child. Not after Hochburg took his parents, not at Dunkirk when German artillery turned the coast to offal. Not even when he lay trapped in the consulate in Angola with no hope of escape. Now the words tumbled from his lips, pleading for this one moment of grace. If only he had enough faith, Madeleine would be waiting.

A gust of air shrieked down the driveway. Nearby Burton heard the shimmer of a wind chime, its sound thin and mournful.

Suddenly he felt exposed: a man walking into the sniper’s sights. He stepped away from the drive. He would reach the house from behind, screened by rows of apple and quince trees. It took him several minutes to make his way there. Once he slipped on the grass, almost fell; close to the ground, he smelled the night’s frost gathering in the soil.

Rows of hawthorns created a natural barrier around the orchard to protect the fruit from the wind. As Burton approached, he sensed something different, something unnatural. It was as if the lay of the land had been distorted. He squeezed through a gap in the hedge and caught sight of the house: the windows were full of shadows, the chimney lifeless. But it wasn’t the farmhouse that absorbed him; instead, his eyes took in the scene around him.

The breath died in Burton’s throat.

He swayed, the haversack toppling from his shoulder. Then his legs sagged and he dropped to his knees.

* * *

Cranley.

Only Cranley could have done this.

Burton had to look away. It was as if he’d taken a blow to his chest, its ferocity deadening his whole body. Two ravens watched him, like sentries in sleek black uniforms.

He had discovered the farm two years earlier. It had been April; he remembered that because of the morning’s news: the Duke and Duchess of Windsor had accepted an invitation to the Führer’s birthday festivities in Germania. People didn’t know whether to be outraged or keep their heads down. Madeleine was at the family’s second home, on the Suffolk coast, for a few days while her husband and Alice remained in London. Burton picked her up, and they drove inland, where there was no chance of meeting someone she knew. They went walking, exploring woods and meadows, stopping for lunch by a tumbledown wall that overlooked the farm. As they ate cheese-and-chutney sandwiches, they daydreamed about living in a place like this. It became one of their regular spots. They were both drawn to the farm’s isolation and weary, dilapidated state. It was a place that yearned for renewal.

Then, the same week they had agreed to make a life together, a FOR SALE sign appeared.

“I don’t believe in coincidence,” said Madeleine, struggling to contain a smile as they drove past.

“Good,” replied Burton. “Neither do I.”

The owner’s son had shown them around, apologizing for how ramshackle everything was. He explained that his father had recently died, that he himself had no urge to stay on: the work was too hard, the profits meager, all the more so given Germany’s agricultural policies. With the vast fertile plains of Russia and endless bounty of Africa, Hitler had achieved his goal of autarky. Thereafter Germany began exporting food, undercutting British farmers.

“Of course there are the orchards,” said the son. “That’s a good business. People will always want English apples.” He led them to the fruit trees, the branches ablaze with blossoms.

“These are quinces,” said Madeleine, gulping down the scent.

“We have apples and quinces,” said the son. “Pears, plums, damsons, cherries.”

“Quinces are my favorite.” She slipped her arm through Burton’s. “Do you know what they represent?”

“Eve took one,” he replied, thinking back to his childhood; his parents had been missionaries. “In the Garden of Eden.”

“I don’t mean fairy tales. In ancient Greece they were eaten by the bride and groom on their wedding night.”

“Really?” He loved the way her mind was a trove of knowledge from a childhood spent in books. “But we don’t believe in coincidences.”

Three months later, after Burton had borrowed a fortune from his aunt, the farm and orchards were theirs. Sometimes Burton wondered if he’d done the right thing: the call to adventure was impossible to silence completely, no matter what he said to reassure Madeleine. There was more work to be done than he’d realized; he discovered he was less good with tools than weapons. But it was the first home he’d had since childhood, and there were moments—repairing a patch of roof, the aroma of burnt toast in the kitchen, Maddie’s slippers nestled by their bed—when he felt a satisfaction he’d never known. A belonging life had denied him.

The grass was soaking into his trousers. Burton stood, his face hot, and startled the ravens. They took to the air, croaking with laughter, and soared into the low, red sun. Burton headed in the opposite direction, walking through the orchard.

Cranley had taken an axe to the trees, hacking them down. Trees that cropped showers of golden fruit, that had built their rings over decades, were reduced to stumps. It had been done some time ago, guessed Burton, before the winter: the exposed wood was blackened with frost. Split bowers lay strewn across the ground like bodies gunned down on a battlefield.

The act itself looked frenzied, as if Cranley had been unable to control himself. Burton heard him in his head: the terrible chopping sound, trunks cracking as they tumbled. Cranley howling. Not all the trees had been felled. Some showed gaping wounds but were still standing; others remained untouched altogether. Burton reached out for an intact one. Needed the reassurance of the bark against his palm.

Acid was swilling in his gullet; he wanted to vomit. And with it came a fury to surpass Cranley’s, a fury that had been growing inside him for months.

He climbed over a trunk and continued to the house—

Stopped immediately.

He’d seen someone in an upstairs window. A face in the gloom, the outline of a white shirt and tie. Then the figure was gone, only the sway of the curtain suggesting a stranger in his home.

Burton surveyed the destruction in the orchard. They were waiting for him. Maybe Cranley himself.

Good, he thought, the rage leavening in him. Good.

He reached for his Browning, tugging it from his belt, and headed toward the farmhouse.

Copyright © 2015 Guy Saville.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Guy Saville is the author of The Afrika Reich, an international bestseller. Born in 1973, Saville has lived in South America and North Africa, and is currently based in the UK