The Intersection of Noir and Horror

By John Woods

October 22, 2020

Many of my favorite novels are not easily classified and often fall under that nebulous term “Literary Fiction.” But I value my origins. As a teenager, I learned to love reading through the Horror genre, and I knew just where to go in the stacks to find Stephen King and Anne Rice. When I later read Lord of the Flies, Heart of Darkness, Blood Meridian, and The Bell Jar, I understood I was actually reading horror stories, ones that somehow bit closer to the bone.

As a writer, I dislike the concept of genre. Mostly because the categorization of art influences and restricts interpretation. Genre, of course, serves a functional purpose. We label books to differentiate their content, and we enjoy the familiar conventions that resonate with us. Genre also determines a novel’s form through these boundaries, and there is great beauty in those established aesthetics and tropes.

But what I enjoy most is when these borders bleed together, especially between the genres of Noir and Horror.

Genre cannot be defined without generalizations. What follows are only my generalizations.

Noir is a subgenre within crime fiction that creates an atmosphere of moral ambiguity. It depicts a dark world where our most sacred values become meaningless abstractions, because the societal institutions meant to uphold these values are corrupt. There is no reliable source of truth, no answers to false promises. Justice is a lie. Honesty becomes foolish. The powerful exploit the weak, and there are no heroes. Against this bleak environment, characters struggle to survive and make sense of a world gone wrong. In Noir, detectives are often traumatized and behave like the criminals they pursue, all while trying to solve crimes in a futile quest for justice, their best efforts crushed by an indifferent universe and the immutable forces of human nature. Noir can also shift focus away from detectives and overturn standard crime narratives by turning criminals and murderers into sympathetic protagonists, who become humans with complex motives rather than villainous caricatures. This nuance allows for the exploration of difficult questions about the nature of society and humanity. By focusing on antiheroes and amoral protagonists, the ethical constructs of crime and justice and right and wrong become questionable in a world where nothing is black and white.

This uncertainty defines Noir, and more than any other genre, Noir reflects the dark realities of our own world. This is why readers are so drawn to the genre.

It is worth noting that Noir seems most appreciated in Europe. I suspect this is because Europeans understand the fragility of human society, particularly democracy. After centuries of violence, European history is a graveyard of fallen ideals, religions, governments, and nations. This may be why America, a relatively young and confident republic, seems more receptive to the escapist qualities of standard crime fiction.

Standard crime stories are often morally straightforward, where crime is an obvious breach of the social contract. Virtuous detectives hunt down bad guys, and at the end of the narrative, criminals are punished, or they get away with their crimes. But we know how to feel about what has happened. Some moral principle has been upheld, or has failed. The murderer is exposed and defeated, or the murderer is still out there, but we are certain of our own moral footing, because we are not criminals.

Noir denies us this clarity. There are no good guys and bad guys, no heroes and villains, and the very idea of that distinction becomes absurd. The world is gray, identities are uncertain, and in these shadows good and evil appear illusory. This angst, this existential doubt, has horrific implications, which I feel are often overlooked.

And so, the lines begin to blur.

What is Horror? When I think of conventional Horror, I imagine the otherworldly, the supernatural—vampires, ghosts, werewolves, zombies, and demons. Creatures from beyond our conception of reality that haunt and feed upon us. Monsters that prey on humans. Of course, these supernatural creatures function as metaphors for the darkest elements of human nature. These monsters reflect our base desires, instincts, and fears.

In this way, Horror stories have always functioned like moral parables. By creating monstrous others, the Horror genre establishes and enforces clear lines between good and evil. In a standard Horror story, an evil force challenges human goodness, and goodness either wins or loses. This is the exact same straightforward, ethical resolution found in most crime fiction. There’s a stake in the vampire’s heart, and we can all sleep safely now. Or, the vampire is still out there, lurking in the dark, but we can take righteous comfort in knowing we are not vampires, not yet.

This is the escapist quality to Horror, which is rightfully fun and unapologetic. Horror confronts the darkness of our world while also transforming it into something wondrous and mysterious. The aesthetics of Horror transfigure our fear of death into something romantic, our fear of other people, and ourselves, into symbolic forms that distance us from our own monstrosity.

But just as Noir is the dark side of crime fiction, there is an even darker aspect to Horror. And this is where Noir and Horror intersect.

The very existence of supernatural forces strikes us on a subliminal, existential level. Like Noir, it is not merely that people are not who they say they are—the vampire that is a handsome stranger, the beautiful woman that is a sinister ghost—it is that the world is not what it appears to be. Supernatural monsters shatter our belief systems, our illusions. When the kind man shifts into the werewolf, when the sweet child’s eyes turn a demonic red, when our friendly neighbors turn into zombies and rip people apart, our understanding of reality is fundamentally questioned. The air blackens. The overarching theme in Horror is that dark forces rest at the core of the world, hidden from us.

The Horror writer Thomas Ligotti articulates this well in his examination of philosophical pessimism. In The Conspiracy Against the Human Race, he states:

Behind the scenes of life lurks something pernicious that makes a nightmare of our world.

Here, Ligotti reveals the subliminal core of every Horror story, but he also echoes the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, who had a similar suspicion when examining our own world, which is the world Noir inhabits:

This world could not be the work of an all-good being, but rather that of a devil who had summoned into existence creatures, in order to gloat over the sight of their agony.

In both cases, these horrific intuitions destabilize the universe, and any moral order we believed it possessed, either through a benevolent God or the harmonic designs of nature. In Horror, the universe is not just indifferent. It is insidious. The unnatural becomes natural, and our conception of the world becomes foundationless.

All of this encapsulates my interest in and early attraction to the Horror genre. For me, the essence of Horror is cognitive assault, discovering the world is not what we think it is, that the people we love are strangers, and the values we believe in do not exist.

When joined together, these Noir and Horror elements create an authentic sense of existential dread, which I believe is the most powerful emotion art can produce, and perhaps conquer. This intersection creates a disturbing atmosphere that feels “real,” that lacks the palatable and comforting distance the supernatural often brings. By focusing on all too human antiheroes struggling in a gray, unsettling world that mirrors our own, we come to an abyss where the existence of morality itself is questioned.

Examples of this intersection are such novels as Crime and Punishment, No Country for Old Men, Gone Girl, American Psycho, Hold the Dark, and The Stranger. Works like this walk along the borderlands between Noir and Horror, novels that portray a dark world without answers or resolution, where our moral compass no longer functions, and our values become unconvincing.

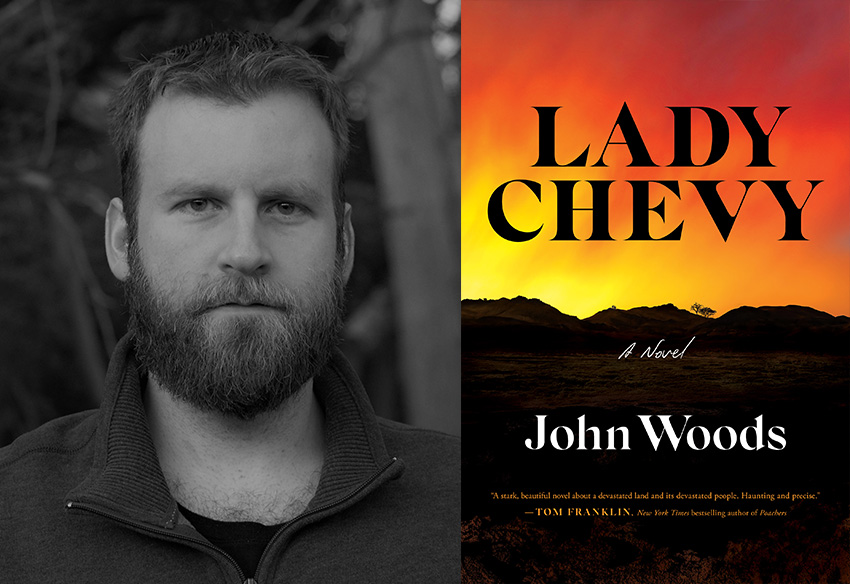

I write what I want to read. My debut novel, Lady Chevy, is not easily categorized. It is a work of literary Noir. It is a crime novel, a mystery and a thriller. But maybe most of all, I feel, it is a Horror story. All my writing is set in Appalachian Ohio and takes place in the same fictitious universe, shaped by these literary influences.

Lady Chevy is the story of Amy Wirkner, an eighteen-year-old senior determined to become a veterinarian and escape her hometown in the dark foothills of Appalachian Ohio, an isolated region under siege by the natural gas industry. Soon after Amy’s parents lease their land to a fracking company, Amy’s brother is born with neurological problems. And while she believes fracking is poisoning her family and community, other toxicities possess the town. Nicknamed “Chevy” for her size, Amy endures the cruelty of her classmates and does well in school, but is haunted by her family’s white supremacist nature. Her grandpa is a former Grand Dragon of the KKK, and his violent presence overshadows the unhappiness in Amy’s impoverished home, her alcoholic father and enigmatic mother. In pursuing a scholarship to attend college, Amy only finds encouragement and support from her uncle, a veteran of the Iraq war who has become a Neo-Nazi survivalist. Amy tells us, “These are my ingredients, the genetic swirls that make me a person, that sometimes make me feel strong and valuable, that often make me feel monstrous.” One night, Amy’s best friend incites her to take part in an act of ecoterrorism against a fracking rig, to avenge her baby brother. The fallout is disastrous. A man is dead, and Amy’s future is threatened. The local police are closing in, but to escape punishment Amy must first confront her own family’s murderous history.

I find most writing about rural America is fixated either on bucolic ideals or backwoods stereotypes. I think the truth is much more mysterious and disturbing. My novel explores the silent despair of small-town life, environmental decay, and the rise of fascistic thinking in America.

We are living through horrific times. I do not feel this is a hyperbolic statement. As I write this, modern civilization is destabilized by a global pandemic, ecological collapse, economic fragility, and social strife. Civil bonds are becoming untethered. Empathy is dying. Several years ago, I wrote Lady Chevy as a cautionary tragedy, to speak to such times, to confront our fears and the forces that influence them.

While sitting in her Civics class, listening to her teacher mythologize America’s foundational principles and democratic values, Amy Wirkner has this intuition:

The ground beneath us is not unsteady.

It simply doesn’t exist.

This fear speaks to our current moment. As the world transforms, we are approaching an uncertain and dreadful edge, a place that exists at the intersection of Noir and Horror.