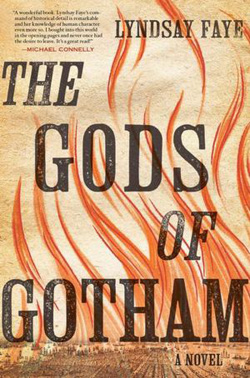

An excerpt from The Gods of Gotham by Lyndsay Faye (available March 15, 2012).

An excerpt from The Gods of Gotham by Lyndsay Faye (available March 15, 2012).

1845. New York City forms its first police force. The great potato famine hits Ireland. These two seemingly disparate events will change New York City. Forever.

Timothy Wilde tends bar near the Exchange, fantasizing about the day he has enough money to win the girl of his dreams. But when his dreams incinerate in a fire that devastates downtown Manhattan, he finds himself disfigured, unemployed, and homeless. His older brother obtains Timothy a job in the newly minted NYPD, but he is highly skeptical of this new “police force.” And he is less than thrilled that his new beat as a “copper star” is the the down-and-out Sixth Ward—at the border of Five Points, the world’s most notorious slum.

One night while making his rounds, Wilde literally runs into a little slip of a girl—a girl not more than ten years old—dashing through the dark in her nightshift . . . covered head to toe in blood.

Chapter 1

When I set down the initial report, sitting at my desk at the Tombs, I wrote:

On the night of August 21, 1845, one of the children escaped.

Of all the sordid trials a New York City policeman faces every day, you wouldn’t expect the one I loathe most to be paperwork. But it is. I get snakes down my spine just thinking about case files.

Police reports are meant to read “X killed Y by means of Z.” But facts without motives, without the story, are just road signs with all the letters worn off. Meaningless as blank tombstones. And I can’t bear reducing lives to the lowest of their statistics. Case notes give me the same parched-headed feeling I get after a night of badly made New England rum. There’s no room in the dry march of data to tell why people did bestial things—love or loathing, defense or greed. Or God, in this particular case, though I don’t suppose God was much pleased by it.

If He was watching. I was watching, and it didn’t please me any too keenly.

For instance, look what happens when I try to write an event from my childhood the way I’m required to write police reports:

In October 1826, in the hamlet of Greenwich Village, a fire broke out in a stable flush adjacent to the home of Timothy Wilde, his elder brother, Valentine Wilde, and his parents, Henry and Sarah; though the blaze started small, both of the adults were killed when the conflagration spread to the main house by means of a kerosene explosion.

I’m Timothy Wilde, and I’ll say right off, that tells you nothing. Nix. I’ve drawn pictures with charcoal all my life to busy my fingers, loosen the feeling of taut cord wrapped round my chest. A single sheet of butcher paper showing a gutted cottage with its blackened bones sticking out would tell you more than that sentence does.

But I’m getting better used to documenting crimes now that I wear the badge of a star police. And there are so many casualties in our local wars over God. I grant there must have been a time long ago when to call yourself a Catholic meant your bootprint was stamped on Protestant necks, but the passage of hundreds of years and a wide, wide ocean ought to have drowned that grudge between us, if anything could. Instead here I sit, penning a bloodbath. All those children, and not only the children, but grown Irish and Americans and anyone ill-starred enough to be caught in the middle, and I only hope that writing it might go a way toward being a fit memorial. When I’ve spent enough ink, the sharp scratch of the specifics in my head will dull a little, I’m hoping. I’d assumed that the dry wooden smell of October, the shrewd way the wind twines into my coat sleeves now, would have begun erasing the nightmare of August by this time.

I was wrong. But I’ve been wrong about worse.

Here’s how it began, now that I know the girl in question better and can write as a man instead of a copper star:

On the night of August 21, 1845, one of the children escaped.

The little girl was aged ten, sixty-two pounds, dressed in a delicate white shift with a single row of lace along the wide, finely stitched collar. Her dark auburn curls were pulled into a loose knot at the top of her head. The breeze through the open casement felt hot where her nightdress slipped from one shoulder and her bare feet touched the hardwood. She suddenly wondered if there could be a spyhole in her bedroom wall. None of the boys or girls had ever yet found one, but it was the sort of thing they would do. And that night, every pocket of air seemed breath on flesh, slowing her movements to sluggish, watery starts.

She exited through the window of her room by tying three stolen ladies’ stockings together and fixing the end to the lowest catch on the iron shutter. Standing up, she pulled her nightgown away from her body. It was wet through to her skin, and the clinging fabric made her flesh crawl. When she’d stepped blindly out the window clutching the hose, the August air bloated and pulsing, she slid down the makeshift rope before dropping to an empty beer barrel.

The child quit Greene Street by way of Prince before facing the wild river of Broadway, dressed for her bedroom and hugging the shadows like a lifeline. Everything blurs on Broadway at ten o’clock at night. She braved a flash torrent of watered silk. Glib-eyed men in double vests of black velvet stampeded into saloons cloaked from floor to ceiling in mirrors. Stevedores, politicians, merchants, a group of newsboys with unlit cigars tucked in their rosy lips. A thousand floating pairs of vigilant eyes. A thousand ways to be caught. And the sun had fallen, so the frail sisterhood haunted every corner: chalk-bosomed whores desperately pale beneath the rouge, their huddles of five and six determined by brothel kinships and by who wore diamonds and who could only afford cracked and yellowing paste copies.

The little girl could spot out even the richest and healthiest of the street bats for what they really were. She knew the mabs from the ladies instantly.

When she spied a gap in the buttery hacks and carriages, she darted like a moth out of the shadows. Willing herself invisible, winging across the huge thoroughfare eastward. Her naked feet met the slick, tarry waste that curdled up higher than the cobbles, and she nearly stumbled on a gnawed ear of corn.

Her heart leaped, a single jolt of panic. She’d fall—they’d see her and it would all be over.

Did they kill the other kinchin slow or quick?

But she didn’t fall. The carriage lights veering off scores of plate-glass windows were behind her, and she was flying again. A few girlish gasps and one yell of alarm marked her trail.

Nobody chased her. But that was nobody’s fault, really, not in a city of this size. It was only the callousness of four hundred thousand people, blending into a single blue-black pool of unconcern. That’s what we copper stars are for, I think . . . to be the few who stop and look.

She said later that she was seeing in badly done paintings—everything crude and two-dimensional, the brick buildings dripping watercolor edges. I’ve suffered that state myself, the not-being-there. She recollects a rat gnawing at a piece of oxtail on the pavement, then nothing. Stars in a midsummer sky. The light clatter of the New York and Harlem train whirring by on iron railway tracks, the coats of its two overheated horses wet and oily in the gaslight. A passenger in a stovepipe hat staring back blankly the way they’d come, trailing his watch over the window ledge with his fingertips. The door open on a sawdusty slaughter shop, as they’re called, half-finished cabinetry and dismembered chairs pouring into the street, as scattered as her thoughts. Then another length of clotted silence, seeing nothing. She reluctantly pulled the stiffening cloth away from her skin once more.

The girl veered onto Walker Street, passing a group of dandies with curled and gleaming soaplocks framing their monocles, fresh and vigorous after a session with the marble baths of Stoppani’s. They thought little enough of her, though, because of course she was running hell for leather into the cesspit of the Sixth Ward, and so naturally she must have belonged there.

She looked Irish, after all. She was Irish. What sane man would worry over an Irish girl flying home?

Well, I would.

I lend considerably more of my brain to vagrant children. I’m much closer to the question. First, I’ve been one, or near enough to it. Second, star police are meant to capture the bony, grime-cheeked kinchin when we can. Corral them like cattle, then pack them in a locked wagon rumbling up Broadway to the House of Refuge. The urchins are lower in our society than the Jersey cows, though, and herding is easier on livestock than on stray humans. Children stare back with something too hot to be malice, something helpless yet fiery when police corner them . . . something I recognize. And so I will never, not under any circumstances, never will I do such a thing. Not if my job depended on it. Not if my life did. Not if my brother’s life did.

I wasn’t musing over stray kids the night of August twenty-first, though. I was crossing Elizabeth Street, posture about as stalwart as a bag of sand. Half an hour before, I’d taken my copper star off in disgust and thrown it against a wall. By that point, however, it was shoved in my pocket, digging painfully into my fingers along with my house key, and I was cursing my brother’s name in a soothing inner prayer. Feeling angry is far and away easier for me than feeling lost.

God damn Valentine Wilde, I was repeating, and God damn every bright idea in his goddamned head.

Then the girl slammed into me unseeing, aimless as a torn piece of paper on the wind.

I caught her by the arms. Her dry, flitting eyes shone out pale grey even in the smoke-sullied moonlight, like shards of a gargoyle’s wing knocked from a church tower. She had an unforgettable face, square as a picture frame, with somber swollen lips and a perfect snub nose. There was a splash of faint freckles across the tops of her shoulders, and she lacked height for a ten-year-old, though she carried herself so fluid that she can seem taller in memory than in person.

But the only thing I noticed clearly when she stumbled to a halt against my legs as I stood in front of my house that night was how very thoroughly she was covered in blood.

Chapter 2

To the first of June, seven thousand emigrants had arrived . . . and the government agent there had received notice that 55,000 had contracted for passage during the season, and nearly all from Ireland. The number expected to come to Canada and the States is estimated by some as high as 100,000. The rest of Europe will probably send to the States 75,000 more.

•New York Herald, summer 1845 •

Becoming a policeman of the Sixth Ward of the city of New York was an unwelcome surprise to me.

It’s not the work I imagined myself doing at twenty-seven, but then again I’d bet all the other police would tell it the same, since three months ago this job didn’t exist. We’re a new-hatched operation. I suppose I’d better say first how I came to need employment, three months back, in the summer of 1845, though it’s a pretty hard push to talk about that. The memory fights for top billing as my ugliest. I’ll do my best.

On July eighteenth, I was tending bar at Nick’s Oyster Cellar, as I’d done since I was all of seventeen years old. The squared-off beam of light coming through the door at the top of the steps was searing the dirt into the planked floor. I like July, the way its particular blue had spread over the world when I’d worked on a ferryboat to Staten Island at age twelve, for instance, head back and mouth full of fresh salt breeze. But 1845 was a bad summer. The air was yeasty and wet as a bread oven by eleven in the morning, and you could taste the smell of it at the back of your throat. I was fighting not to notice the mix of fever sweat and the deceased cart horse half pushed into the alley round the corner, as the beast seemed by degrees to be getting deader. There are meant to be garbage collectors in New York, but they’re a myth. My copy of the Herald lay open, already read back to front as is my morning habit, smugly announcing that the mercury was at ninety-six and several more laborers had unfortunately died of heatstroke. It was all steadily ruining my opinion of July. I couldn’t afford to let my mood sour, though. Not on that day.

Mercy Underhill, I was sure of it, was about to visit my bar. She hadn’t done so for four days, and in our unspoken pattern that was a record, and I needed to talk to her. Or at least try. I’d recently decided that adoring her was no longer going to stand in my way.

Nick’s was laid out in the usual fashion for such places, and I loved its perfect typicalness: a very long stretch of bar, wide enough for the pewter oyster platters and the dozens of beer tumblers and the glasses of whiskey or gin. Dim as a cave, being half underground. But on mornings like that one the sun cut through wonderfully, so we didn’t yet need the yellow-papered oil lamps that sent friendly smoke marks up the plaster. No furniture, just a series of booths with bare benches lining the walls, curtained if you wanted although no one ever closed them. Nick’s wasn’t a place for secrets. It was a forum for the frantic young bulls and bears to scream things across the room after a twelve-hour stint at the Exchange, while I listened.

I stood pouring off a gallon of whiskey for a ginger boy I didn’t recognize. The East River’s bank swarms with rickety foreign creatures trying to shake off their sea legs, and Nick’s was on New Street, very close to the water. The lad waited with his head tilted and his little claws on the cedar bar plank. He stood like a sparrow. Too tall to be eight years old, too scared to be ten. Hollow-boned, eyes glassily seeking free scraps.

“This for your parents?” I wiped my fingers on my apron, corking the earthenware jug.

“For Da.” He shrugged.

“Twenty-eight cents.”

His hand came out of his pocket with a ragtag assortment of currency.

“Two shillings makes two bits, so I’ll take that pair and wish you welcome. I’m Timothy Wilde. I don’t pour shallow, and I don’t water the merchandise.”

“Thankee,” he said, reaching for the jug.

There were dark treacle stains at the underarms of his tattered shirt due to the last molasses barrel he’d gammed from being too high, I saw next. So my latest customer was a sugar thief. Interesting.

That’s a typical saloon keeper’s trick: I notice a great many things about people. A fine city barman I’d be if I couldn’t spot the difference between a Sligo dock rat with a career in contraband molasses and the local alderman’s son asking after the same jug of spirits. Barmen are considerably better paid when they’re sharp, and I was saving all the coin I could lay hands on. For something too crucial to even be called important.

“I’d change professions, if I were you.”

The bright black sparrow’s eyes turned to slits.

“Molasses sales,” I explained. “When the product isn’t yours, locals take exception.” One of his elbows shifted, growing more fluttery by the second. “You’ve a ladle, I suppose, and sneak from the market casks when their owners are making change? All right, just quit the syrups and talk to the newsboys. They make a good wage too, and don’t catch beatings when the molasses sellers have learned their sly little faces.”

The boy ran off with a nod like a spasm, clutching the sweating jug under his wing. He left me feeling pretty wise, and neighborly to boot.

“It’s useless to counsel these creatures,” Hopstill intoned from the end of the bar, sipping his morning cup of gin. “He’d have been better off drowned on the way over.”

Hopstill is a London man by birth, and not very republican. His face is equine and drooping, his cheeks vaguely yellow. That’s due to the brimstone for the fireworks. He works as a lightning-maker, sealed away in a garret creating pretty explosions for theatricals at Niblo’s Gardens. Doesn’t care for children, Hopstill. I don’t mind them a bit, admiring candor the way I do. Hopstill doesn’t care for Irish folk either. That’s common enough practice, though. It doesn’t seem sporting to me, blaming the Irish for eagerly taking the lowest, filthiest work when the lowest, filthiest work is all they’re ever offered, but then fairness isn’t high on the list of our city’s priorities. And the lowest, filthiest work is getting pretty hard to come by these days, as the main of it’s already been snapped up by their kin.

“You read the Herald,” I said, fighting not to be annoyed. “Forty thousands of emigrants since last January and you want them all to join the light-fingered gentry? Advising them is only common sense. I’d sooner work than steal, myself, but sooner steal than starve.”

“A fool’s exercise,” Hopstill scoffed, pushing his palm through the sheaves of grey straw that pass for his hair. “You read the Herald. That rank patch of mud is on the brink of civil war. And now I hear tell from London that their potatoes have started rotting. Did you hear about that? Just rotting, blighted as a plague of ancient Egypt. Not that anyone’s surprised. You won’t catch me associating with a race that’s so thoroughly called down the wrath of God.”

I blinked. But then, I had often been shocked by the sage opinions bar guests had gifted me regarding the members of the Catholic church, the only breathing examples they’d ever seen being the Irish variety. Bar guests who were otherwise—for all appearances—perfectly sane.

First thing the priests do with the novice nuns is sodomize them, and the priests as do thoroughest work rise up the ranks, that’s the system—they aren’t even fully ordained until their first rape is done with. Why, Tim, I thought you savvied the pope lived off the flesh of aborted fetuses; it’s common enough knowledge. I said no way in hell, is what, the very idea of letting an Irish take the extra room, what with the devils they summon for their rituals, would that be right with little Jem in the house?

Popery is widely considered to be a sick corruption of Christianity ruled by the Antichrist, the spread of which will quash the Second Coming like an ant. I don’t bother responding to this brand of insanity for two reasons: idiots treasure their facts like newborns, and the entire topic makes my shoulders ache. Anyhow, I’m unlikely to turn the tide. Americans have been feeling this way about foreigners since the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798.

Hopstill misread my silence as agreement. He nodded, sipping his spirits. “These beggars shall steal whatever isn’t nailed down once they arrive here. We may as well save our breath.”

It went without saying that they would arrive. I walk along the docks edging South Street only two blocks distant on my way home from Nick’s pretty often, and they boast ships thick as the mice, carrying passengers plentiful as the fleas. They have done for years—even during the Panic, when I’d watched men starve. There’s work to be had again now, railways to lay and warehouses to be built. But whether you pity the emigrants or rant about drowning them, on one subject every single citizen is in lockstep agreement: there’s an unholy tremendous amount of them. A great many Irish, and all of those Catholics. And nearly everyone concurs with the sentiment that follows after: we haven’t the means nor the desire to feed them all. If it gets any worse, the city fathers will have to pry open their wallets and start a greeting system—some way to keep foreigners from huddling in waterfront alleys, begging crusts from the pickpockets until they learn how to lift a purse. The week before, I’d passed a ship actively vomiting up seventy or eighty skeletal creatures from the Emerald Isle, the emigrants staring glassy-eyed at the metropolis as if it were a physical impossibility.

“That’s none too charitable, is it, Hops?” I observed.

“Charity has nothing to do with it.” He scowled, landing his cup on the counter with a dull ping. “Or rather, this particular metropolis will have nothing to do with charity in cases where charity is a waste of time. I should sooner teach a pig morals than an Irishman. And I’ll take a plate of oysters.”

I called out an order for a dozen with pepper to Julius, the young black fellow who scrubbed and cracked the shells. Hopstill is a menace to cheerful thought. It was hovering on the tip of my tongue to mention this to him. But just then, a dark gap cut into the spear of light arrowing down the stairs and Mercy Underhill walked into my place of employment.

“Good morning, Mr. Hopstill,” she called in her tender little chant. “And Mr. Wilde.”

If Mercy Underhill were any more perfect, it would take a long day’s work to fall in love with her. But she has exactly enough faults to make it ridiculously easy. A cleft like a split peach divides her chin, for instance, and her blue eyes are set pretty wide, giving her an uncomprehending look when she’s taking in your conversation. There isn’t an uncomprehending thought in her head, however, which is another feature some men would find a fault. Mercy is downright bookish, pale as a quill feather, raised entirely on texts and arguments by the Reverend Thomas Underhill, and the men who notice she’s beautiful have the devil’s own time of it coaxing her face out of whatever’s latest from Harper Brothers Publishing.

We try our best, though.

“I require two pints . . . two? Yes, I think that ought to do it. Of New England rum, please, Mr. Wilde,” she requested. “What were you talking of?”

She hadn’t any vessel, only her open wicker basket with flour and herbs and the usual hastily penned scraps of half-finished poetry keeking out, so I pulled a rippled glass jar from a shelf. “Hopstill was proving that New York at large is about as charitable as a coffin vendor in a plague town.”

“Rum,” Hopstill announced sourly. “I didn’t take either you or the reverend for rum imbibers.”

Mercy smoothed back a lock of her sleek but continually escaping black hair as she absorbed this remark. Her bottom lip rests just behind her top lip, and she tucks the bottom one in slightly when she’s ruminating. She did then.

“Did you know, Mr. Wilde,” she inquired, “that elixir proprietatis is the only medicine that can offer immediate relief when dysentery threatens? I pulverize saffron with myrrh and aloe and then suffer the concoction to stand a fortnight in the hot sun mixed with New England rum.”

Mercy passed me a quantity of dimes. It was still good to see so many disks of metal money clinking around again. Coins vanished completely during the Panic, replaced by receipts for restaurant meals and tickets for coffee. A man could hew granite for ten hours and get paid in milk and Jamaica Beach clams.

“That’ll teach you to question an Underhill, Hops,” I advised over my shoulder.

“Did Mr. Hopstill ask a question, Mr. Wilde?” Mercy mused.

That’s how she does it, and damned if it doesn’t fasten my tongue to my teeth every single time. Two blinks, a gauzy lost lamb expression, a remark she pretends is unrelated, and you’re hung up by your toes. Hopstill sniffed blackly, understanding he was good as banished from the continent. And by a girl who turned twenty-two this past June. I don’t know where she learns such things.

“I’ll carry this as far as your corner,” I offered, turning out from behind the bar with Mercy’s spirits.

Thinking all the while, Are you really going to do this? I’d been fast friends with Mercy for well over a decade. It could all stay the same. You lifting things for her and watching the curl at the back of her neck and working out what she’s reading so you can read it too.

“Why are you leaving your bar?” She smiled at me.

“I’ve been gripped by a spirit of adventure.”

New Street was as warm, the sheen of polished sable beaver hats punishing my eyes above the sea of navy frock coats. It’s only a two-block street terminating to the north at Wall, all giant stone storefronts with awnings shielding the pedestrians from the scorching blaze. Pure commerce. From every canopy hangs a sign, and plastered to every sign and glued to every wall is a poster: parti-colored neckerchiefs, ten for a dollar. Whitting’s hand soap a guarantee against ringworm. All the populous streets on the island are papered in shrieking broadsheets, no exceptions, the flaked headlines of yesteryear just visible under the freshly glued advertisements. I glimpsed my brother Val’s smirk translated into woodcut and tacked to a door, then caught myself stifling a grimace: Valentine Wilde supports the formation of the New York City police force.

Well and good. I’d probably oppose it, in that case. Crime is rampant, robbery expected, assault common, murder often unsolved.

But supposing Val was in favor of the violently debated new police, I’d take my chances with anarchy. Up to the previous year, apart from a recently formed group of hapless men called Harper’s Police, who wore blue coats to advertise themselves as fit for beatings by the spirited, there was no such thing as a Peeler in this town. There was a Watch in New York, certainly. They were ancient hangdogs parched for money who toiled all day and then slept all night in watchmen’s booths, ardently watched by the brimming population of criminals. We’d in excess of four hundred thousand souls prowling the streets, counting the perpetual piebald mob of visitors from around the globe. And less than five hundred watchmen, snoring in vertical coffins as their dreams bounced around like tenpins inside their leather helmets. As for daylight keepers of the peace, don’t even ask. There were nine of them.

But if my brother Valentine is in favor of something, that something isn’t particularly likely to be a good idea.

“I thought you might want a bruiser to get you past the throng,” I remarked to Mercy. It was half a joke. I’m solid, and quick too, but a bantam. An inch taller than Mercy, if I’m lucky. But Napoleon didn’t figure height stood between him and the Rhineland, and I lose fights about as often as he did.

“Oh? Oh, I see. Well, that was very kind, then.”

She wasn’t actually surprised; the set of her robin’s-egg-blue eyes told me that much, and I decided to watch my step. Mercy is very difficult to navigate. But I know my way around the city, and around Mercy Underhill. I was born in a cheerless cottage in Greenwich Village before New York even touched its borders, and I’d been learning Mercy’s quirks since she was nine.

“I wonder something this morning.” She paused, her wide-set eyes sliding my way and then dropping off again.“ But it’s silly, maybe. You’ll laugh.”

“If you ask me not to, I won’t.”

“I wonder why you never use my name, you see, Mr. Wilde.”

New York’s winds are never fresh in the summer. But as we turned onto Wall, bank after bank scrolling past us in line after line of Grecian columns, the air turned sweeter. Or maybe I just remembered it that way afterward, but suddenly it all seemed pure dust and hot stone. Clean, like parchment. That smell was worth a fortune. “I don’t know what you mean,” I said.

“There, yes. I’m sorry—I don’t mean to be cryptic.” Mercy’s bottom lip slid underneath her top one just a little, only a fraction of a warm wet inch, and I thought in that moment I could taste it too. “You could have just said, ‘I don’t know what you mean, Miss Underhill.’ And then we wouldn’t be talking about it any longer.”

“What does that make you think?”

I spied a jagged hole in the pavement. Pivoting quickly, I guided Mercy out of its path with a swish of her pale green summer skirts. Maybe she’d caught sight of the little cave herself, though, for I didn’t startle her. Her head didn’t even turn. Escorting Mercy down a block, depending on her mood, you might not be there for all the attention she pays you. And I’m not exactly Sunday, so to speak. I’ve never been a special occasion. I’m all of the other days in the workweek, and there are plenty of us streaming by without notice. But I could fix that, or I thought I could.

“Do you mean to make me theorize that you like the topic of my name, Mr.Wilde?” she asked me, looking as if she was trying not to laugh.

I’d caught her out, though. No one ever answers her questions with questions, just the way she never acknowledges answering questions at all. That’s another fault of Mercy’s I’m fixed on. She’s a reverend’s daughter, to be certain, but she talks clever as a jade if only you’re keen enough to notice.

“Do you know what I’d like to do?” I questioned in return, thinking that was the trick of it. “I’ve managed to put some money away, four hundred in cash. Not like all these maniacs who take their first extra dollar and play it against the price of China tea. I want to buy some land, out on Staten Island maybe, and have a river ferry. Steamships are dear, but I can take my time finding a good price.”

I remembered being two years orphaned, scrawny and pale-skinned and twelve. Wheedling my way through sheer tenacity into the employment of a hulking but kindly Welsh boatman during one of the leaner periods Valentine and I had ever faced, having lived off of mealy apples for a week. Maybe I was hired on as a deckhand because the fellow suspected as much. I recalled standing at the prow of the ferry before the rails I’d just polished until my fingers were peeling, head thrown back as an ecstatic midsummer thunderstorm exploded in the still-blazing sunshine. For five minutes, spray and rain had danced in the dazzling light, and for five minutes, I’d not wondered whether my brother back on Manhattan Island had yet managed to kill himself. It felt wonderful. Like being erased.

Mercy quickened her grip slightly. “What has your anecdote to do with my question?”

Be a man and take the plunge, I thought.

“Maybe I don’t want to call you Miss Underhill, ever,” I answered her. “Maybe I’d like to call you Mercy. What is it you’d like best to be called?”

I was at a touchstone at Nick’s Oyster Cellar that night, a lightning-bright lucky charm. All my pale glorified card sharps, all the faro, champagne-morphine-and-what-else-have-you addicts, the freaks who haunt the Exchange and make deals with damp handshakes in the back rooms of coffee houses—they all saw kismet on me and wanted a taste of it. A drink from Timothy Wilde was as good as a slap on the back from an Astor.

“Three more bottles of champagne!” shouted a weedy fellow called Inman. He could scarce breathe for being jostled by black-coated elbows. I wondered sometimes what made the financiers head for another sweltering cock-pit the moment they quit the chamber of the Board of Brokers.

“Take a glass for yourself on my account, Tim, cotton’s higher than an opium fiend!”

People tell me things. Always have done. They hemorrhage information like a slit bag spills dried beans. It’s only gotten worse as I’ve manned an oyster cellar. Incredibly useful, but it does get to be draining at times—as if I’m part barman and part midnight hole in the ground, just a quick-dug hollow to bury secrets in. If Mercy would only manage to fall into the same habit, that would be something miraculous.

A stream of honest working sweat trickled down my back by nine o’clock, when the sun went down. Men sweating for other reasons demanded drinks and oysters as if the world had spun off its axis. Apparently there was nothing for it but to annihilate the feast before we all slid off. I was moving fast enough for a dozen, juggling orders, calling back friendly insults, counting the shower of coins.

“What’s the good news, Timothy?”

“We’ve got enough cold champagne to float an ark on,” I shouted back at Hopstill, who’d reappeared. Julius materialized behind me, hoisting a bucket of fresh-shaved ice. “Next round’s on the house.”

The way I figured it, Mercy Underhill hadn’t said no to any of my remarks. Nor “You seem to have the wrong idea,” nor “Leave me be.” Instead, she’d said a good many completely unrelated things before I left her at the corner of Pine and William streets, a breeze picking up from the east, where the coffee houses churned rich burning smells into the heavy air.

She’d said, “I can understand your not liking my family name, Mr. Wilde. It makes me think of being buried,” for example. She’d said, “Your own parents, God rest them, had the generosity to leave you the surname of a lord chancellor of England. I’d love to live in London. How cool London must be in the summer, and there the parks have real grass, and everything electric green from the rain. Or so my mother always told me, whenever a New York summer seemed too much to bear.” That was a regular catechism of Mercy’s, whatever the season—a little prayer to her late mother, Olivia Underhill, a native of London who’d been odd and generous and imaginative and beautiful and wonderfully like her only child.

Mercy had added, “I’ve finished the twentieth chapter of my novel. Don’t you think that’s a thrilling number? Had you ever expected me to get so far? Will you give me your honest opinion, once it’s finished?”

If she aimed to discourage me, she was going to have to up her game.

And I might not be a scholar in title, or a churchman, but Reverend Thomas Underhill liked me fine. Barmen are pillars of the community and the hub of New York’s wheel, and I had four hundred dollars in slick silver buried in the straw tick of my bed. Mercy Underhill, in my opinion, ought to be called Mercy Wilde—and then I’d never know where another conversation was headed for the rest of my life.

“Give me fifty dollars and I’ll see you’re a rich man by the end of the fortnight, Tim!” shrieked Inman from yards away in the roiling vat of bodies. “Sam Morse’s telegraph can make you a king!”

“Take your fairy money and go to hell,” I returned cheerfully, reaching for a slop rag. “You ever play the market, Julius?”

“I’d likelier burn money than speculate it,” Julius answered without looking at me, deftly pulling the corks from a row of drenched champagne bottles with his wide fingers. He’s a sensible fellow, quick and quiet, with fragrant tea leaves braided into his hair. “Fire can heat a man’s soup. You calculate they know the Panic was their doing? You think they remember?”

I wasn’t listening to Julius any longer by that time. Instead, I was dwelling thick as laudanum on the last thing Mercy had said to me.

Don’t think you’ve hurt my feelings. I’m not married to the name, after all.

It was the only sentence directly to the purpose I’d ever heard her say, I think. At least, it was the first since she was about fifteen, and even so, the remark had a sideways charm to it. So that was a heady, graceful moment. The moment when I discovered that Mercy saying something near-plain is every bit as beautiful as Mercy talking circles like a flame-red kite in the wind.

At four in the morning, I passed Julius an extra two dollars as he propped the mop handle in the corner. He nodded. Worn to a thinly buzzing alertness, we headed for the steps leading up to the awakening city.

“You ever wonder what it’s like to sleep at nighttime?” I asked as I locked the cellar door behind us.

“You won’t catch me in a bed after dark. Keep the devil guessing,” Julius answered, winking at his own joke.

We reached the street just as dawn flared with grasping red fingers over the horizon. Or so the corner of my eye thought, as I settled my hat on my head. Julius was quicker to catch on.

“Fire!” Julius bellowed in his low, smooth voice, cupping his hands around his sharply defined lips. “Fire in New Street!”

For a moment, I stood there, frozen in the dark with a streak of scarlet above me, already acting about as useless as a broken gas-lamp inspector. Feeling the same sickness in my belly the word fire always causes me.

Copyright ©2012 Lyndsay Faye

Lyndsay Faye is the author of Dust and Shadow and The Gods of Gotham, coming March 2012, from Amy Einhorn Books/Putnam. She tweets @LyndsayFaye.

AUA is one of the best Caribbean Medical University to study medicine with its accredited programs.