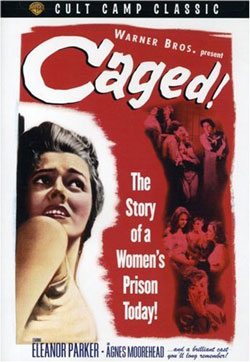

Jenji Kohan’s Netflix series Orange Is The New Black is doing amazing things with the Women In Prison genre—creating a deeply moving, and often funny, portrait of life behind bars. But she’s drawing on a film tradition that back decades. That tradition reached its highest point with John Cromwell’s 1950 Caged, the Citizen Kane of Women In Prison flicks.

Jenji Kohan’s Netflix series Orange Is The New Black is doing amazing things with the Women In Prison genre—creating a deeply moving, and often funny, portrait of life behind bars. But she’s drawing on a film tradition that back decades. That tradition reached its highest point with John Cromwell’s 1950 Caged, the Citizen Kane of Women In Prison flicks.

Eleanor Parker stars as Marie Allen, an innocent nineteen year-old widow who has been sentenced from 1-to-15 years for sitting in a car while, unknown to her, her husband knocked over a gas station. Her husband wound up dead and now Marie is in the joint where she’s told that she must “Get tough or die.” She’s recruited to be part of a gang run by a butch convict named Kitty Stark and her sidekick, Smoochie, but Marie politely refuses. She just wants to serve out the first ten months of her sentence until she can get paroled.

But things won’t be that easy. The prison is run by a stern but kindly warden named Benton (played with intelligence and sensitivity by Agnes Moorehead), but it’s managed on the cell block level by a hulking monster named Evelyn Harper (Hope Emerson). Miss Harper runs roughshod over the girls, demanding money for protection and dishing out brutal punishments for small infractions. It’s a trope of this subgenre that the real danger always comes from the guards, not the other inmates. For camp purposes, this teases the audience with expressions of the dominant/submissive relationship, but if this is the stuff of S&M fantasy, it can also be the stuff of serious drama. This film might have some elements that have been appropriated as camp stereotypes—Kitty Stark tells Marie suggestively at one point, “Get this through your head: if you stay in here too long, you don’t think of guys at all. You just get out of the habit”—but like Jules Dassin’s 1947 men-in-prison picture Brute Force, Caged is a film that finds serious faults with the penal system.

In some ways, in fact, you might argue that Caged is more honest than Brute Force when it comes to its characters. Dassin’s film, for all its many virtues, treats its inmates as victims. Caged actually lets its characters have flaws, substantial flaws in some cases. They’re criminals, many of them happily so. That they are still victims of a flawed penal system makes this film more, not, less complicated and adds to the drama.

In some ways, in fact, you might argue that Caged is more honest than Brute Force when it comes to its characters. Dassin’s film, for all its many virtues, treats its inmates as victims. Caged actually lets its characters have flaws, substantial flaws in some cases. They’re criminals, many of them happily so. That they are still victims of a flawed penal system makes this film more, not, less complicated and adds to the drama.

The film was directed with great skill by John Cromwell, a noted stage actor and, by 1950, a rather undistinguished veteran film director in Hollywood. The following year, he would be blacklisted on the testimony of, among others, his RKO boss Howard Hughes. Cromwell was not the most impressive artist to go down to the witch hunters—indeed, much of his work is uninspired (and he managed to make one of the worst film noirs, Dead Reckoning, despite having Bogart and Lizabeth Scott in the cast). Cromwell needed a good script to work from, and with Caged, he had a firecracker. Written by Phantom Lady screenwriter Bernard Schoenfeld, the script was based on research ex-journalist Virginia Kellogg gained by incarcerating herself in women’s prisons. The plot is standard good-girl-goes-to-jail stuff, but the details of enforced monotony and self-defeating bureaucracy have the smack of authenticity.

Cromwell’s direction is superb. The film opens from a prisoner’s point-of-view in the back of a dank, dark transport truck, and from this haunting opening shot to the thrilling, and deliciously ironic, last scene Cromwell and his ace cinematographer Carl E. Guthrie give Caged the full noir visual treatment. Look at the scene where Miss Harper taunts Kitty Stark with the news that Stark’s rich and well-connected rival Elvira Powell is coming to the joint—bad news for Kitty since she won’t be able to compete with Elvira’s cash and influence. Cromwell and Guthrie put the camera at a slant under the women. Kitty is on a bunk, evil Miss Harper looming over her, and over Miss Harper, spread out against the ceiling like the top of a cage, are the shadows of steel bars. As Miss Harper walks away laughing, her shadow meshes with the bars as if she’s become a part of the cage itself.

The nearly all-female cast is uniformly excellent, but three performances stand out. Most obviously, Hope Emerson creates one of the all-time great villains in Miss Harper. Most commentators read her character as an angrily-repressed lesbian, and indeed the scene where she visits the girls dressed up for the evening and tells them about her boyfriend seems to be more about taunting them with what she knows they want than the truth of any real engagement. We never see the boyfriend, and I suspect that Miss Harper walked outside and caught the bus home for the evening. Emerson excelled at playing butch villains (see her other great performance in Cry of the City), but she’s matched here by a butch heroine in the form of Betty Garde’s Kitty Stark. At first, Kitty comes on like a stereotype of the threatening bulldyke (indeed, she basically created the cinematic stereotype with this performance), but by the end she’s become a heroic figure. Broken by Miss Harper, she manages to find enough strength for one final gesture of defiance. And what a gesture it is. You’ll never look at a fork the same way.

The nearly all-female cast is uniformly excellent, but three performances stand out. Most obviously, Hope Emerson creates one of the all-time great villains in Miss Harper. Most commentators read her character as an angrily-repressed lesbian, and indeed the scene where she visits the girls dressed up for the evening and tells them about her boyfriend seems to be more about taunting them with what she knows they want than the truth of any real engagement. We never see the boyfriend, and I suspect that Miss Harper walked outside and caught the bus home for the evening. Emerson excelled at playing butch villains (see her other great performance in Cry of the City), but she’s matched here by a butch heroine in the form of Betty Garde’s Kitty Stark. At first, Kitty comes on like a stereotype of the threatening bulldyke (indeed, she basically created the cinematic stereotype with this performance), but by the end she’s become a heroic figure. Broken by Miss Harper, she manages to find enough strength for one final gesture of defiance. And what a gesture it is. You’ll never look at a fork the same way.

Finally, the film is fortunate to have Eleanor Parker as the innocent Marie Allen at its center. Marie must “get tough or die” and it’s up to the actress to convince us that this transformation is real. Parker succeeds on all counts: as the trembling, innocent girl, as the slowly embittering woman, and finally as the dame with a steel spine. The last scene of the film, which I will not give away, is hugely satisfying. The system treated her like an animal and cast her into a pit where she had to fight to survive. And so she did; Marie Allen got tough.

Finally, the film is fortunate to have Eleanor Parker as the innocent Marie Allen at its center. Marie must “get tough or die” and it’s up to the actress to convince us that this transformation is real. Parker succeeds on all counts: as the trembling, innocent girl, as the slowly embittering woman, and finally as the dame with a steel spine. The last scene of the film, which I will not give away, is hugely satisfying. The system treated her like an animal and cast her into a pit where she had to fight to survive. And so she did; Marie Allen got tough.

Other Essential Women In Prison Movies

1. Manslaughter (1922)-Cecil B. De Mille directed this, the first full-fledged WIP.

2. The Godless Girl (1929)-De Mille goes back inside.

3. Ladies They Talk About (1933)-A hardass Barbra Stanwyck goes behind bars.

4. Women’s Prison (1955)-Psychotically repressed warden Ida Lupino tortures her prisoners.

5. 99 Women (1969)-Director Jess Franco goes all-in on the kink factor.

6. The Big Doll House (1971)-Pam Grier and friends bust out of a concentration camp.

7. The Big Bird Cage (1972)-Pam Grier busts a group of women out of a concentration camp.

8. Black Mama White Mama (1973)-Pam Grier busts out of a concentration camp. Note: If you try to lock up Pam Grier, she will kick your ass.

9. Caged Heat (1974)-Jonathan Demme made his directorial debut with this WIP flick

See More from Criminal Element's Week Behind Bars.

Jake Hinkson, the Night Editor, is the author of The Posthumous Man.

For a great overview of the WIP genre, check out this essay by filmmaker Oren Shai [url=http://brightlightsfilm.com/79/79-women-in-prison-movies-cinema-genre-caged_shai.php#.UgT8dqyJmSo]”The Women In Prison Film: 1922-1974 From Reform to Revolution” [/url]