Knoedler & Company began in 1846 as the Manhattan outpost of the French printmaker Goupil et Cie. It was America’s first storefront art gallery; it predated the Metropolitan Museum of Art by 24 years. During the Gilded Age, Knoedler moved from peddling inexpensive prints to dealing Old Master artworks to the likes of Vanderbilt, Morgan, and Frick.

By 1970, the new breed of robber barons had different tastes. Knoedler was in trouble. Oil tycoon Armand Hammer bought the place in 1971 and installed new management who made the leap to selling Modern art (roughly, Impressionism and its sequels to 1940). It also went back to its roots by selling original prints by LeRoy Neiman, who was huge back then.

The gallery began representing big-name artists such as Richard Diebenkorn and Robert Rauschenberg. Its age and reputation made it a go-to place for purchasing Modern and contemporary art. Being displayed in or represented by Knoedler could be a huge boost for an artist’s career.

Armand Hammer died in 1990. His grandson Michael took over, fell out with the management team, and pissed off Neiman, whose sales kept Knoedler afloat. In 1994, Hammer kicked out Lawrence Rubin, the gallery’s über-competent director, and replaced him with Ann Freedman, whom Rubin had hired as a gallery assistant back in the ‘70s.

Freedman says she’s a dealer and lover of art but not an expert or connoisseur. She’s a born saleswoman, though, and had built a contact list that included many of the major collectors in the Northeast. Still, Rubin’s treatment brought hard feelings. Neiman left the gallery (taking his print sales with him), as did a number of the other name-brand artists. Once again, Knoedler faced an existential crisis.

It was then that Freedman met Glafira Rosales, a Long Island art dealer. If Knoedler played in the big leagues, Rosales was at best on a farm team.

Rosales said she was selling a collection of original canvases painted by the leading lights of the Abstract Expressionist movement. Her client had inherited them from “Mr. X,” a Swiss/Mexican collector who’d bought the works directly from the artists. “Mr. X Jr.” was from a wealthy family and simply didn’t like the paintings, so he’d told Rosales to get rid of them but not give them away.

Sketchy as it sounds, the art market is one place where this tale wouldn’t seem like science fiction. Freedman saw the story as “a puzzle to be solved,” but says she had no reason to disbelieve it. Besides, given the marquee artists involved, the sales could be a huge blessing to Knoedler. It was like fate had rained unicorns on the struggling gallery.

Freedman jumped in with both feet: she ultimately bought forty paintings from Rosales between 1994 and 2008. None had previously exhibited or were part of the artists’ catalogues raisonné (lists of known works).

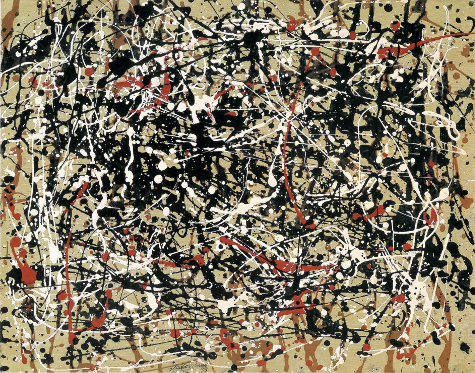

And she made mint. The collectibles market was booming. Nine classes of collectibles—including classic cars, coins, stamps, fine art, and fine wine—all outperformed stocks in the decade ending Sept. 30, 2012. Given that Rosales sold Freedman the canvases at fire-sale prices, Knoedler raked it in as power collectors scooped up “fresh” works by the likes of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Richard Diebenkorn.

The first sign of trouble came in 2001.

Jack Levy, head of M&A for Goldman Sachs, bought four paintings from Knoedler, including a Pollock, Untitled 1949. He agreed to pay $2 million for the Pollock (Rosales had charged the gallery $750,000) as long as the International Foundation for Art Research authenticated it. After two years’ work, however, IFAR—a respected nonprofit that produces scholarly and technical information about works of art—said that it couldn’t find any support for the Pollock’s provenance (history). Understandably put out, Levy returned the painting to Knoedler and got his money back. Freedman, the gallery, and impresario David Mirvish each bought shares in the painting and planned to sell it for $15 million when the market drove up the price.

Freedman asked Rosales some probing questions after this debacle. The story behind the paintings morphed: in this version, “Mr. X” became romantically involved with David Herbert, a fixture in the 1950s New York gay art scene. Herbert had taken “Mr. X” to the artists’ studios, where he bought the paintings with cash so the sales wouldn’t show up in his tax records. “Mr. X” eventually returned to his wife in Switzerland, dragging his paintings along with him. “Mr. X Jr.” could quietly sell the collection now that both his father and Herbert were dead.

Freedman claimed to believe Rosales and later said she researched the Herbert story, though neither she nor her gallery staff ever turned up any proof. Even though the paintings’ backstory was, shall we say, fluid, Freedman kept selling them.

In 2006, Freedman sold a Richard Diebenkorn watercolor, Untitled (Ocean Park Series) 1972, to the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City. One problem: the Diebenkorn family had warned Freedman in 1995 that this watercolor and at least one other at Knoedler “did not seem genuine.” The Diebenkorn estate discovered the Kemper sale and told the museum about its doubts. The watercolor migrated to the Kemper’s warehouse. A year later, the museum got a replacement: a genuine Diebenkorn from Ann Freedman’s personal collection.

Rosales was involved in selling up to seven of these maybe-fake Diebenkorn watercolors, including at least two through Knoedler. The story she told about their provenance didn’t add up for the artist’s family or for the people connected with the Spanish gallery that supposedly had sold them to Rosales.

In 2006-2007, Jack Flam—president of the Dedalus Foundation, which represents Robert Motherwell’s estate—visited Freedman on several occasions and told her that the stories behind a total of seven Motherwells hanging in Knoedler and Freedman’s private collection didn’t hold water. Freedman later sold one of the paintings without mentioning Flam’s doubts. Knoedler hired a forensic conservator in 2007 to examine these paintings; the conservator also called them shady. Freedman dismissed his verdict by saying, “He knew nothing about Robert Motherwell.”

In November 2007, Freedman sold a previously unknown Jackson Pollock to hedge-fund manager Pierre Lagrange for $17 million. She claimed that the painting was going to show up in a supplement to the Pollock catalogue raisonné (there was no supplement) and that twelve Pollock experts had authenticated it (they hadn’t). This was a rerun of a deal from three years earlier when she unloaded a Mark Rothko canvas on Domenico and Eleanore De Sole for $8.3 million (cost to Knoedler: $950K). During that sale, Freedman told the De Soles that she knew “Mr. X Jr.” personally and gave them a list of eleven Rothko experts whom she said had authenticated the piece.

The De Soles kept their Rothko. But when Lagrange tried to sell his Pollock through Sotheby’s and Christie’s in 2010, both auction houses turned him down, saying the provenance didn’t pass the smell test.

Enough smoke was flying around Rosales’s “David Herbert collection” that the FBI launched an investigation into Rosales and Knoedler in 2009. A grand jury subpoena hit Knoedler in the summer. The gallery marked the remaining “Herbert collection” paintings “not for sale.”

Freedman abruptly resigned from Knoedler in October 2009 without telling anyone why. She still claims it wasn’t about the FBI investigation.

Selling Rosales’s paintings had kept the gallery afloat for years. Without these profits, Knoedler’s finances hit the skids. The gallery put its posh Upper East Side home at 19 East 70th Street on the market for $59 million in December 2009; it finally sold in February 2011 for $31 million.

Meanwhile, Killala Fine Art in Ireland filed suit in Federal court against Julian Weissman, a former Knoedler associate director now running his own gallery. They claimed that Weissman bought a forged Motherwell from Rosales and sold it to Killala. It was the first lawsuit connected with Rosales’s paintings but not the last. Killala and Weissman settled in October 2011: Killala got $650,000; the Dedalus Foundation got $200,000 and the satisfaction of stamping the “Motherwell” with a label calling it a forgery.

Pierre Lagrange had been trying for over a year to get Knoedler to return his money. The Killala settlement inspired him to have a consultant examine his supposed Pollock. The consultant discovered paint that didn’t exist until after the artist died. Lagrange presented the consultant’s report to Knoedler on November 29, 2011.

On November 30th, Knoedler announced it was closing … immediately.

Lagrange and the De Soles filed two of the eleven lawsuits thrown against Knoedler and Freedman. Most were settled in the plaintiffs’ favor. Because of the settlements, Freedman hasn’t yet been found guilty of fraud or even had to testify. Today she runs a small New York City gallery.

In 2013, Rosales finally admitted that she’d sold $80 million worth of forged paintings through Knoedler, Weissman’s gallery, and her own gallery. She pleaded guilty to pushing over sixty forgeries as well as to money laundering and tax evasion. Pei-Shen Qian, a 73-year-old Chinese artist working in a garage in Queens, created most of the fakes. Qian—who said he didn’t know that Rosales was selling his works as real—skedaddled to China to avoid arrest.

The FBI investigation located only thirty-four of Rosales’s paintings. The rest are still out there.

How much did Freedman know? She continues to claim she’s another victim. “I was a perfect mark,” she told The Art Newspaper in an exclusive 2016 interview, calling Rosales and her cronies “exquisitely conspiratorial wizards.” She points to the Rosales pieces she bought with her own money; would she pony up for fakes? However, other gallerists say that Rosales’s low prices should have raised a big red flag with Freedman. Also, her claims to the De Soles that she knew “Mr. X Jr.” personally and her repeated failure to follow up on all the warnings she got from various experts suggest that she was either complicit or extraordinarily gullible. We may never know the truth.

As Jason Hernandez, former Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, told Artnet.com, “A case like this tends to wake people up.” Several of the scammed buyers say they never thought to question the word of a gallery as respectable as Knoedler. As we’ve discovered in other areas, a venerable name isn’t much of a guarantee of straight dealing (Wells Fargo, anyone?).

Maybe Ann Freedman’s greatest gifts to the art market will be constructive paranoia on the buyers’ side and self-awareness on the sellers’ side. Or more likely, the players in this game will just hope their gift horses keep their mouths shut.

Want more art crime? Read Lance Charnes's article on Operation Antiquity!

Lance Charnes is an emergency manager and former Air Force intelligence officer. His latest art-crime novel The Collection involves a disgraced gallerist’s search for a cache of stolen paintings that may be in the hands of the Calabrian mafia. His Facebook author page features spies, shipwrecks, art crime and archaeology, among other things.

I don’t think Goupil et Cie peddled “inexpensive prints.” They published reproductions of otherwise-unobtainable artworks, and print runs could earn the equivalent of millions of dollars, or at least hundreds of thousands of dollars, in today’s money. And individual prints could cost–what?–$10-20 apiece? In other words, a lot of money for the mid-19th century.

I think you were generally at least upper middle class if you owned Goupil et Cie prints.

I’d like to own Goupil et Cie prints today, but I can’t afford them. I think good examples could cost you $350-$1,500.

According to what I found, Goupil sold across the whole gamut — original works, engraved luxury reproductions, and “mass-produced” (to the extent that was possible back then) prints for the middle class. Ken Johnson’s 2001 NYT art review “[url=http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/20/arts/art-review-a-return-to-the-junction-of-art-and-commerce.html]A Return to the Junction Of Art and Commerce[/url]” has some interesting notes on how Goupil operated in the mid-1800s.

I’d come away with the general impression that Goupil’s New York outpost originally concentrated on the lower end of the market, moving upmarket as the Gilded Age progressed. If that’s not so, then my apologies; but Goupil didn’t serve only the carriage trade when it first came to America.