Editor's Note: This entry will kick off a new series on the Final Westerns of the great cowboy stars. First up: Gary Cooper.

Editor's Note: This entry will kick off a new series on the Final Westerns of the great cowboy stars. First up: Gary Cooper.

When The Hanging Tree appeared in movie theaters in 1959 the Western was at its peak. Indeed, no view of the 1950s can be complete without an acknowledgement of the outsized popularity of the cowboy picture. Westerns were simply everywhere. They filled movie houses, and they dominated television programming. They were to the 50s what science fiction is to us now: the shared national escapist fantasy. Before the frontier moved in to outer space, it still lay out west.

There’s a solid argument to be made that the star most responsible for the Western’s popularity was Gary Cooper. In later years, of course, John Wayne would supplant Cooper and lock down the title as the biggest Western star of all time. (For all intents and purposes, John Wayne became the Western.) But while Wayne was big in the fifties, Cooper had been associated with the Western longer and to greater acclaim. More sensitive than Wayne or Randolph Scott but less neurotic than Jimmy Stewart or Henry Fonda, he was, to pinch the title of one of his hits, The Westerner.

He first hit it big in The Winning of Barbara Worth in 1926 and damn-near invented the laidback cowboy character in The Virginian in 1929. Many more Westerns followed (as did comedies, romances, and war films—god, Gary Cooper was great), but the film that cemented his hold on the genre was Fred Zinnemann’s 1952 High Noon. High Noon didn’t invent the so-called “adult Western”—Westerns that were a little more likely to stay in-doors and involve characters who didn’t fit white hat/black hat morality—but it remains the exemplar of the species. The film proved to be a box office blockbuster that won Cooper an Oscar and shaped many of the Westerns that would follow.

By 1959, however, the cowboy was about ready to hang up his hat. Cooper was 58 years old at a time when 58 was old. He belonged to a generation that drank too much and smoked cigarettes all day, every day, almost as a kind of ritual. Not incidentally, it was a generation that died young: Bogart had died at age 57, and Gable would die at 59. Cooper himself would be dead of cancer in less than a year and a half.

He’d made his last great Western, Anthony Mann’s Man Of The West, in 1958. That film had given Cooper a haunted figure to play, an ex-gunman trying to go straight who gets pulled into his old gang once again. Cooper had given one of his best performances in the film, and had it been his last Western it would have sent him out on a very high note indeed.

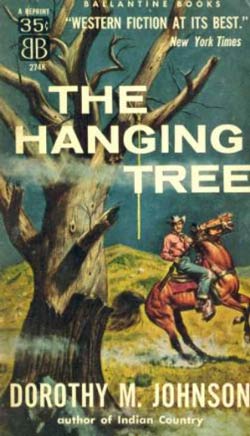

But if The Hanging Tree (directed by the great Delmer Daves, and written by Wendell Mayes and Halsted Welles, from a novel by Dorothy M. Johnson) isn’t on same par as Man Of The West, it does show the kind of figure that Cooper had become by this time. The story follows the sudden appearance of Doctor Joseph Frail (Cooper) in the gold rush town of Skull Creek, Montana. Doc Frail sets up a practice, takes in a wounded stagecoach passenger named Elizabeth (Maria Schell), and butts heads with a drunken faith healer (George C. Scott, in his first feature film).

But if The Hanging Tree (directed by the great Delmer Daves, and written by Wendell Mayes and Halsted Welles, from a novel by Dorothy M. Johnson) isn’t on same par as Man Of The West, it does show the kind of figure that Cooper had become by this time. The story follows the sudden appearance of Doctor Joseph Frail (Cooper) in the gold rush town of Skull Creek, Montana. Doc Frail sets up a practice, takes in a wounded stagecoach passenger named Elizabeth (Maria Schell), and butts heads with a drunken faith healer (George C. Scott, in his first feature film).

The film again finds Cooper as an outcast figure, someone at odds with his small society. In his big, isolated house he takes tentative steps to human connection with Elizabeth, but even there he can’t bring himself to form a real bond. He can protect her against the assaults of a sleazy prospector (Karl Malden, who took on some directorial duties when Daves was out sick), but he can’t have a relationship with her.

Where The Hanging Tree goes wrong, it seems to me, is the way it stacks the deck in favor of Doc Frail. He seems to be the only man in town who isn’t insane, or a rapist, or both. Toward the end of the film, when one of the prospectors strikes it rich, the residents of Skull Creek drunkenly burn their entire town to the ground and try to lynch Doc Frail. This goes beyond being unbelievable behavior—it undermines the last third of the drama by forcing the issue of the Individual Against His Society. One thing that a film like High Noon did right was to give everyone in town an individual perspective. Here, the townsfolk are simply a faceless, malevolent force. It’s interesting to note this kind of anti-social slant in a major motion picture staring a cinematic legend, but that doesn’t mean that it makes for good drama.

Yet, I hasten to add that the best thing about the picture is that cinematic legend himself. Gary Cooper had always been an actor uncommonly comfortable with silence, imbued with the screen actor’s greatest gift: his face registered thought on camera. Orson Welles once explained to Peter Bogdanovich that while Cooper knew nothing of craft, he simply came across on camera. On the set, Welles explained, Cooper seemed to be doing nothing. Once his performance was projected onscreen, however, it turned out the camera had caught some magic not visible to the naked eye.

By the time he made The Hanging Tree, Cooper had assembled one of the greatest careers in the Golden Age. In addition to helping create the Western hero in The Virginian, he helped Capra define the Everyman in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Meet John Doe (the director once said, “Gary Cooper just looks like America to me”), helped create the screwball comedy with Lubitsch in Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife and Howard Hawks in Ball of Fire, was Hollywood’s biggest leading man in the war years (he won his first Oscar for Hawks’s patriotic call to arms Sergeant York in 1941), and gave his iconic performance as the beleaguered lawman in High Noon in 1952. His career was a towering body of work. The Hanging Tree may not be the best film he ever made, but it ends his Western career on a subdued and thoughtful note.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of The Posthumous Man and Saint Homicide.

Read all posts by Jake Hinkson for Criminal Element.

PS: The Hanging Tree is now available at the Warner Archive.

Very interesting post on a great film. Thanks. I always preferred Gary Cooper, Glenn Ford, and Randolph Scott to John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart as western heros, not to knock the later two who turned out some fine flicks. But I think films like Man of the West, Vera Cruz, 3::10 to Yuma, Jubal, and Seven Men From Now really capture the West, unlike a lot the the by-the-numbers Wayne and Stewart flicks of the 60s and 70s.

I’ve always appreciated Cooper’s intelligent adult westerns. Thanks for the review, Jake.

Nicely thought through and expressed. I received a copy of Hanging Tree for Christmas and have been too slowly getting around to it. I concur with you about Cooper. He can get so quiet on screen, you can almost hear the watch ticking in his pocket. (McQueen was like that, too.)

Your comment about The Virginian makes me wonder how much that performance was influenced by the decades of stage productions, dating back to Dustin Farnum’s. So glad, too, that Barbara Worth was not lost. Cooper is so iconic in that role, he really deserves to win the girl (except the novel has it otherwise). Nice job, thanks. I look forward to more in this series.